Central cranial diabetes insipidus: what it is and why it matters

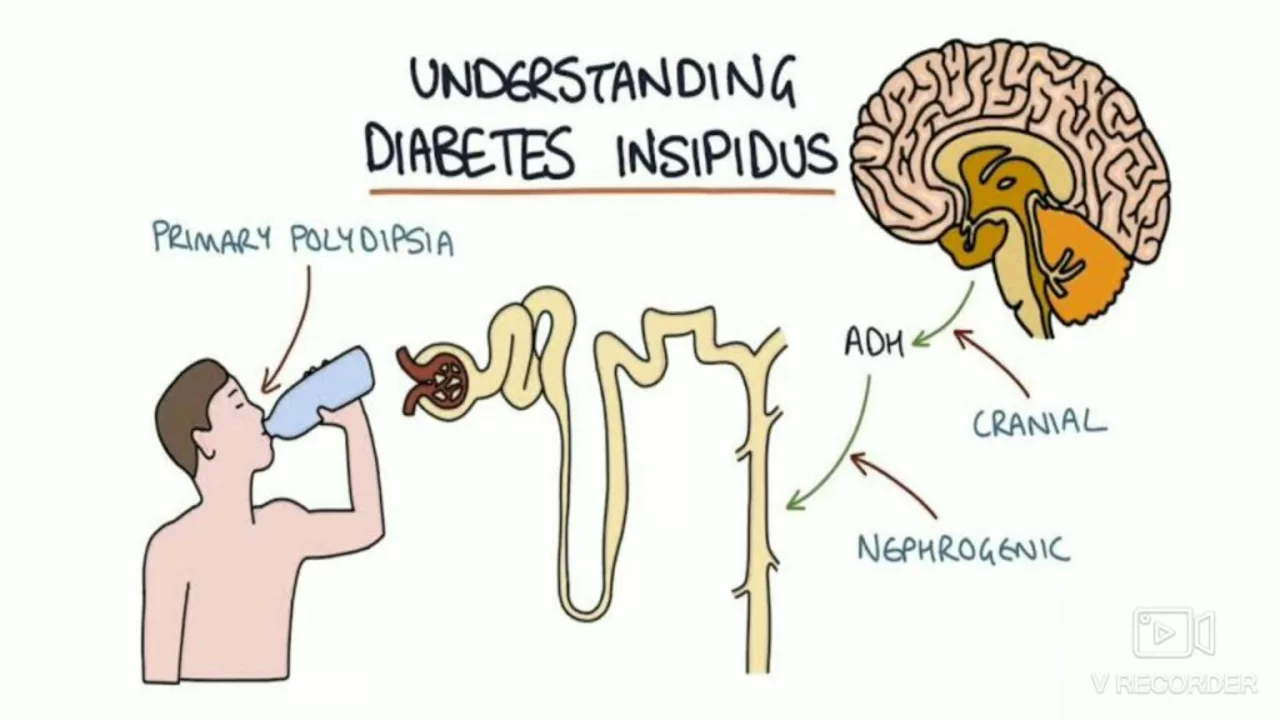

Central cranial diabetes insipidus (CDI) happens when the brain stops making or releasing enough antidiuretic hormone (ADH). Without ADH, the kidneys can’t concentrate urine, so you pee a lot and get very thirsty. It’s not the same as diabetes mellitus—blood sugar is usually normal. If you’ve noticed sudden heavy urination and constant thirst, CDI is one condition your doctor will consider.

What causes CDI?

CDI usually starts because something affects the hypothalamus or pituitary stalk/posterior pituitary. Common causes are head trauma, pituitary surgery, tumors (like craniopharyngioma), infections, and sometimes autoimmune or genetic problems. In many adults the cause stays unknown and is labeled idiopathic. Knowing the trigger matters because treatment and follow-up depend on it.

How is CDI different from nephrogenic diabetes insipidus? CDI is an ADH problem in the brain. Nephrogenic DI is when the kidneys don’t respond to ADH even though the hormone is present. The symptoms look the same, so tests are needed to tell them apart.

How it's diagnosed

If a doctor suspects CDI they check urine volume, urine concentration, and blood sodium. Typical findings: very dilute urine and raised serum sodium. The water deprivation test can show whether the body can concentrate urine when fluids are limited. Giving desmopressin (a synthetic ADH) and watching the urine response helps confirm central DI—if urine concentrates after desmopressin, the problem is central.

MRI of the brain, focused on the pituitary, is often ordered to look for tumors, inflammation, or structural damage. If recent head injury or surgery happened, that history can point the way. Blood tests may check for other hormone problems if the pituitary is involved.

Treatment and follow-up

The main treatment for CDI is desmopressin (DDAVP). It replaces ADH and reduces urine output and thirst. Desmopressin comes as a nasal spray, oral tablets, or injection. Doctors start with a low dose and adjust based on urine output and blood sodium. Too much desmopressin can cause low sodium, so regular monitoring is important.

Treating the underlying cause matters too: surgery or radiation for a tumor, antibiotics for infection, or careful monitoring after head injury. People with CDI need periodic checks of electrolytes and kidney function. During illness, travel, or changes in fluid intake, dose adjustments may be required.

When should you seek urgent care? If you feel dizzy, very weak, confused, or have seizures—these can be signs of dangerously high or low sodium. Also get help for rapid weight loss from fluid loss or inability to control thirst and urination.

CDI can be managed well when diagnosed early and followed by an endocrinologist. With the right tests, medication, and a treatment plan tailored to the cause, most people return to a good quality of life while keeping careful watch on fluids and sodium levels.

Diagnosing Central Cranial Diabetes Insipidus: Tests and Procedures

- Jul, 1 2023

- Daniel Remedios

- 16 Comments

In my recent exploration, I focused on the diagnostic processes involved in identifying central cranial diabetes insipidus. I found that doctors often perform blood and urine tests initially to check for low sodium levels and high urine output. Water deprivation tests and MRI scans are also used to confirm the diagnosis and assess the pituitary gland's condition. Desmopressin tests can then help to distinguish between central and nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. It's a detailed process, but crucial for ensuring accurate diagnosis and treatment.