There’s no such thing as a vaccine generic in the way we think of generic pills for high blood pressure or cholesterol. That’s not a technicality-it’s a structural barrier that’s kept billions of people in low-income countries waiting for vaccines while wealthier nations stocked their clinics. Unlike a simple chemical drug that can be copied once the patent expires, vaccines are living systems. They’re made from viruses, cells, proteins, and complex molecules that can’t be replicated with a lab recipe. Even if you have the exact formula, you still need the right facility, the right equipment, the right supply chain, and the right expertise to make them. And none of that is easy to build-or cheap.

Why Vaccines Can’t Be Generic Like Pills

When a drug like atorvastatin goes off patent, any manufacturer can start making it. The FDA lets them skip years of clinical trials because they just need to prove it’s the same chemical, in the same dose, working the same way. That’s called bioequivalence. Vaccines don’t work like that. You can’t test a COVID-19 vaccine from a factory in Nigeria against one from Pfizer and say, ‘They’re the same.’ The immune response isn’t measured by blood levels-it’s measured by how well your body fights the virus after injection. And that depends on every tiny detail: the cell line used, the purification method, the lipid nanoparticles that carry mRNA, the stabilizers in the vial. Even a 2% change in one step can make the whole batch useless-or dangerous.

This is why every new vaccine, no matter how similar it looks on paper, needs a full biological license application. There’s no shortcut. The WHO calls it the ‘biological complexity barrier.’ And it’s not just about science. It’s about money. Building a single vaccine production line costs between $200 million and $500 million. That’s not a startup expense. That’s a national infrastructure project.

Who Makes the World’s Vaccines?

Four companies-GSK, Merck, Sanofi, and Pfizer-control about 70% of the global vaccine market. That’s not because they’re the most innovative. It’s because they’re the only ones who’ve ever built the factories, trained the teams, and passed the inspections. The rest of the world plays catch-up.

India stands out. It’s the only country that’s managed to break into this club at scale. The Serum Institute of India, based in Pune, makes more vaccines than any other company on Earth-1.5 billion doses a year. It supplies 70% of the vaccines the WHO buys for global immunization programs. It makes the measles vaccine for 90% of the world’s children. It made the AstraZeneca shot for over 100 countries during the pandemic at $3-$4 per dose, while Western companies charged $15-$20.

But here’s the catch: India doesn’t make the raw materials. It imports 70% of its vaccine ingredients from China and the U.S. That became a crisis in April 2021, when India halted exports during its own deadly wave. The U.S. restricted exports of key lipid nanoparticles used in mRNA vaccines. Global vaccine supply dropped by half overnight. Suddenly, countries relying on Indian-made vaccines had nothing. No backup. No plan. Just silence.

The African Paradox: Producing Nothing, Importing Everything

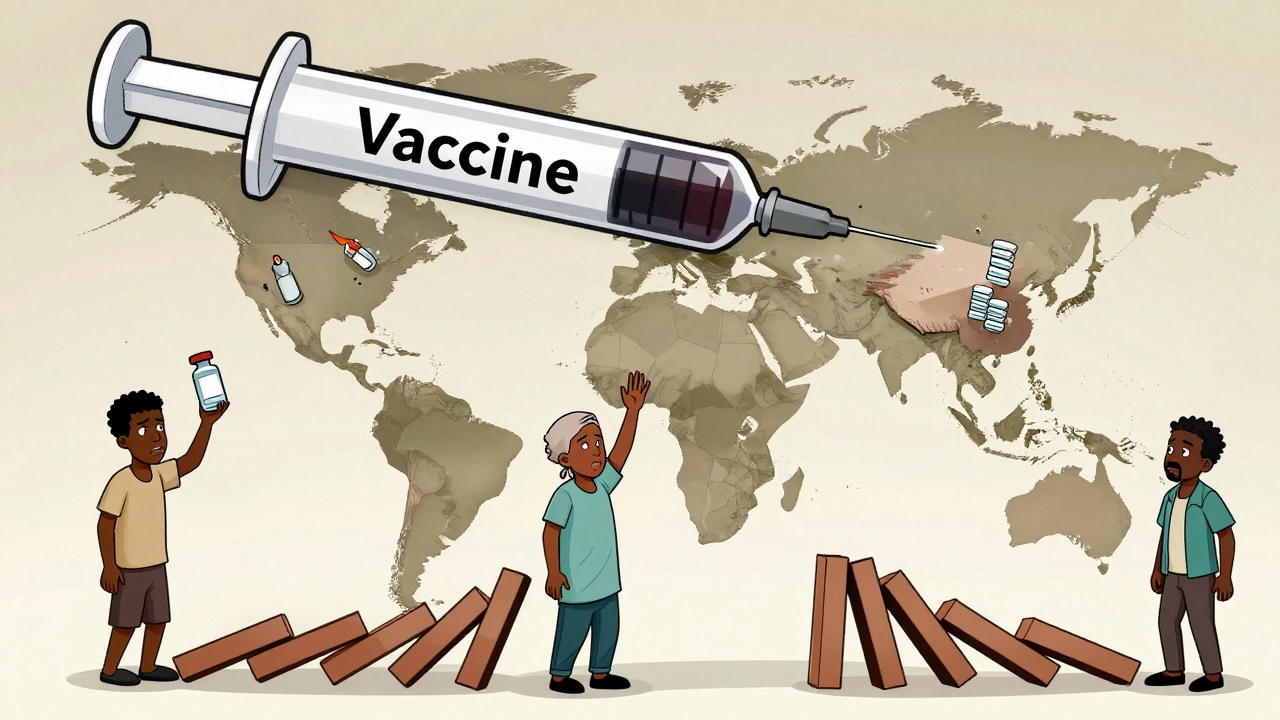

Africa produces less than 2% of the vaccines it uses. Yet, it’s home to some of the world’s most skilled pharmaceutical workers and has the highest burden of vaccine-preventable diseases. In 2021, 83% of all COVID-19 vaccines delivered to Africa through COVAX went to just 10 countries. Twenty-three African nations had vaccinated less than 2% of their people. Meanwhile, the continent imports 99% of its vaccines.

Why? Because no African country has a single facility that can produce mRNA, viral vector, or conjugate vaccines at scale. The African Union estimates it would take $4 billion and 10 years to get to 60% self-sufficiency. That’s a huge investment for countries still struggling to pay for basic health care. And even if they had the money, they’d need the technology. The WHO set up a mRNA tech transfer hub in South Africa in 2021 with help from BioNTech. It took 18 months just to get the first batch made. Why? Because they couldn’t find suppliers for the specialized glass vials, the cold-chain containers, or the lipid nanoparticles. These aren’t things you order off Amazon. They’re made by five companies worldwide.

Supply Chains Are Fragile. And They’re Not Fair.

Vaccine supply chains are like a house of cards. One country restricts an export, and the whole thing collapses. During the pandemic, the U.S. used the Defense Production Act to block exports of critical materials to India. The EU delayed shipments of syringes and vials. Even something as simple as filter membranes used in purification became scarce. These aren’t just logistics problems-they’re power problems.

High-income countries have long-term contracts with manufacturers. They pay upfront. They lock in capacity. They get first dibs. Low-income countries wait. They rely on donations. They get doses that expire in weeks. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, health workers received vials labeled with expiration dates just two weeks away-with no refrigeration to store them. What’s the point of a vaccine if you can’t keep it cold?

And then there’s pricing. Gavi, the global vaccine alliance, negotiates lower prices for poor countries. But even then, the pneumococcal vaccine-a lifesaver for children-still costs over $10 per dose in the poorest nations. That’s more than the cost of a full course of antibiotics. Meanwhile, the same vaccine sells for under $2 in bulk to wealthier countries. The manufacturers say it’s about R&D costs. But when the same company makes the same product in the same factory, how is that fair?

Who’s Trying to Fix This?

Some progress is happening. The WHO’s mRNA hub in South Africa is now producing vaccines. A new facility in Senegal is being built with support from the African Union. Indonesia and Malaysia are investing in their own production lines. But these are drops in the ocean. The world needs 10 billion doses a year just for routine immunization. Add in pandemic preparedness, and we’re talking 20 billion. The current global capacity? Maybe 8 billion.

The U.S. FDA launched a pilot in 2025 to fast-track generic drug approvals for manufacturers based in the U.S. Why? Because over 90% of active pharmaceutical ingredients come from China and India. The FDA admitted that relying on foreign supply chains is a national security risk. But they’re not doing the same for vaccines. Why? Because vaccines are harder. And harder means more expensive. And more expensive means less political will.

Dr. Gagandeep Kang from India put it bluntly: ‘We have the people. We have the experience. But we don’t have the control.’ Control over the raw materials. Control over the technology. Control over the patents. Without all three, countries can’t become independent.

What Needs to Change?

There are three things that would make a real difference:

- Technology transfer must be mandatory. Patents shouldn’t block access during global health emergencies. The WHO’s voluntary pool for mRNA tech has helped a few countries, but it’s too slow. We need a global treaty that forces companies to share know-how when public health is at stake.

- Invest in local manufacturing-not just in Africa, but in Asia and Latin America. Don’t just build factories. Build ecosystems. Train local engineers. Support local suppliers. Make it possible for a country to make its own vials, filters, and stabilizers.

- Stop treating vaccines like luxury goods. If a vaccine saves lives, it shouldn’t be priced based on what a wealthy country can pay. Global health organizations need to negotiate as a bloc-not as individual nations begging for scraps.

The Serum Institute of India proves it’s possible to make high-quality vaccines at low cost. But they can’t do it alone. They need reliable access to raw materials. They need fair pricing. And they need the world to stop assuming that if a country can make a tablet, it can make a vaccine. It’s not the same. It never was.

By 2025, low- and middle-income countries will still be 70% dependent on vaccine imports. That’s not progress. That’s a failure of global cooperation. And it’s not about money alone. It’s about who gets to decide who lives-and who waits.

Are there real generic vaccines like there are generic pills?

No. Unlike small-molecule drugs, vaccines are complex biological products that cannot be proven bioequivalent through standard testing. Each vaccine requires its own full licensing process, even if it’s nearly identical to another. There’s no abbreviated approval pathway like the FDA’s ANDA for generic drugs.

Why can’t countries just copy vaccine formulas?

Copying the formula is only the first step. Vaccines require specialized manufacturing environments-biosafety labs, ultra-cold storage, precise fermentation systems-and rare raw materials like lipid nanoparticles. Only five global suppliers make these critical components. Even with the formula, building the infrastructure takes 5-7 years and hundreds of millions of dollars.

Why does India produce so many vaccines but still import raw materials?

India is the world’s largest vaccine producer by volume, supplying 70% of WHO’s vaccines. But it imports 70% of its key vaccine ingredients-like cell culture media and lipid nanoparticles-from China and the U.S. This dependency makes its supply chain vulnerable, as seen during the 2021 COVID-19 wave when export restrictions halted global vaccine production.

Is Africa trying to build its own vaccine production?

Yes. The African Union is investing $4 billion to build regional vaccine manufacturing capacity, aiming for 60% self-sufficiency by 2040. The WHO’s mRNA hub in South Africa began production in 2023, but at only 100 million doses per year-less than 1% of global need. Progress is slow due to lack of equipment, materials, and skilled labor.

Why are vaccine prices so high in poor countries?

Manufacturers use tiered pricing, but it’s not always fair. For example, the pneumococcal vaccine costs over $10 per dose in low-income countries, while wealthier nations pay under $2. This is because manufacturers charge what the market can bear. Even with Gavi’s negotiations, there’s no global price cap, and no requirement to share production technology to lower costs.

Can the U.S. or EU help by building more vaccine plants at home?

The U.S. FDA launched a pilot in 2025 to speed up generic drug approvals for U.S.-based manufacturers to reduce reliance on foreign suppliers. But this doesn’t apply to vaccines. Building vaccine plants domestically is extremely expensive and takes years. It also doesn’t solve the global access problem-it just shifts dependence from Asia to North America or Europe.

What’s the biggest obstacle to vaccine equity?

The biggest obstacle is the lack of global political will to share technology and control supply chains. Profit-driven models prioritize wealthy markets. Patents are enforced even during pandemics. And there’s no binding international system to ensure fair access. Without mandatory technology transfer and investment in local manufacturing, inequality will persist.

Courtney Co

I just can't believe we're still having this conversation. People die because some CEO in New York decides it's too expensive to share a recipe? Like, what even is this system? I'm not mad, I'm just disappointed. And honestly? I'm tired.

Priyam Tomar

You're all missing the point. India doesn't make vaccines because it's some heroic underdog-it makes them because it's the cheapest labor hub for Western pharma. The Serum Institute isn't independent, it's a contract manufacturer with a fancy name. And don't get me started on how they're still dependent on China for lipids. This whole narrative is woke propaganda dressed up as equity.

Irving Steinberg

bro like... why is this even a thing?? 🤦♂️ we made pills for decades and now we're stuck because vaccines are 'complex'? sounds like a corporate excuse to charge $20 for something that costs $1 to make. also why are we still using glass vials in 2025? can't we just 3d print them??

Lydia Zhang

The fact that this is even controversial is wild

Kay Lam

I think we need to reframe this entirely. It's not about who can make a vaccine, it's about who gets to decide what counts as medicine. When we treat health like a market good instead of a human right, we're not just failing logistics-we're failing ethics. The infrastructure isn't just about machines and labs, it's about trust. It's about letting communities build their own systems instead of waiting for permission from a handful of corporations and governments who've spent decades controlling the flow. And yes, it takes money. But it also takes courage. And right now, courage is in short supply. We need to stop asking for donations and start demanding sovereignty.

Adrian Barnes

The structural inequity described herein is not merely a matter of economic disparity but rather a systemic manifestation of neocolonial pharmaceutical hegemony. The enforcement of intellectual property rights during a global health emergency constitutes a violation of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, Article 12. Furthermore, the reliance on oligopolistic supply chains for critical inputs-such as lipid nanoparticles-represents a critical vulnerability in global health security architecture. The absence of binding international mechanisms for technology transfer is not an oversight; it is a deliberate policy choice prioritizing shareholder value over human life.

Dennis Jesuyon Balogun

Let me be blunt: Africa doesn’t lack capacity, it lacks agency. We have the scientists, the engineers, the will. But every time we try to build, the West says 'wait, let us help'-and then they sell us the vials at triple price, control the cold chain, and dictate the terms. The mRNA hub in South Africa? Great. But why did it take 18 months just to source a glass vial? Because no one in the Global North wants us to be independent. They want us to be consumers, not creators. This isn’t about money. It’s about power. And until we dismantle that, we’re just rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic.

Grant Hurley

Honestly this whole thing makes me wanna cry and high five at the same time 😭🙌 like yes India is doing the heavy lifting but also why is the world still acting like vaccines are some secret magic spell? We got the tech. We got the people. We just need to stop hoarding the tools. Also can we PLEASE stop calling it 'donations' like we're giving out birthday presents? It's a right, not a favor.

Bee Floyd

There’s something deeply unsettling about how we’ve normalized this. We don’t blink when a child in Lagos dies because the vaccine expired before it reached the clinic. But if a CEO in Zurich misses their quarterly target? We throw a fit. We treat biological survival like a luxury SKU. The real tragedy isn’t the lack of factories-it’s that we’ve stopped imagining a world where life isn’t priced by GDP.

Jeremy Butler

The assertion that patents are the primary impediment to equitable vaccine access is fundamentally flawed. While intellectual property rights may present logistical challenges, the principal determinants of manufacturing scalability are capital intensity, regulatory harmonization, and workforce specialization. To conflate patent enforcement with moral failure is to engage in ideological reductionism. The solution lies not in compulsory licensing but in targeted investment in technical education and infrastructure development within emerging economies.

Shashank Vira

You think this is about vaccines? No. This is about the death of sovereignty. India makes 1.5 billion doses? Brilliant. But they’re still begging for lipids from China like peasants begging for grain. And Africa? They want to build factories but won’t even fund their own supply chains. This isn’t injustice-it’s incompetence dressed up in moral outrage. The world doesn’t owe you a vaccine. You have to earn the right to make one. And right now? Most of you are still in kindergarten.