Lyme Disease Tinnitus Risk Checker

Tick Exposure History

Did you spend time in areas where ticks are common (wooded trails, grassy fields) in the past few weeks?

Symptom Checklist

Which of these symptoms do you currently have? (Select all that apply)

Tinnitus Details

Describe your tinnitus symptoms:

Enter your information and click "Assess Risk Level" to see your risk assessment.

Quick Summary

- Ringing in the ears (tinnitus) can be an early sign of Lyme disease, especially when it appears with fatigue, headache, or joint pain.

- The culprit is Borrelia burgdorferi, the bacterium carried by infected ticks.

- Neurological involvement - called early disseminated Lyme - often produces tinnitus, facial palsy, or meningitis‑like symptoms.

- Diagnosis relies on a clear tick‑exposure history, a physical exam, and two‑tier serologic testing.

- Prompt antibiotic therapy (usually doxycycline) can reverse tinnitus in most cases; delayed treatment may make symptoms linger.

What is Lyme disease?

Lyme disease is a bacterial infection spread by black‑legged ticks that have fed on infected wildlife. First identified in the United States in the 1970s, it has since been reported across Europe, Asia, and parts of the Southern Hemisphere. The disease progresses through three stages: early localized, early disseminated, and late. Each stage brings its own cluster of symptoms, ranging from the classic bull’s‑eye rash to joint inflammation and, importantly for this article, neurological disturbances like tinnitus.

Why does ringing in the ears happen?

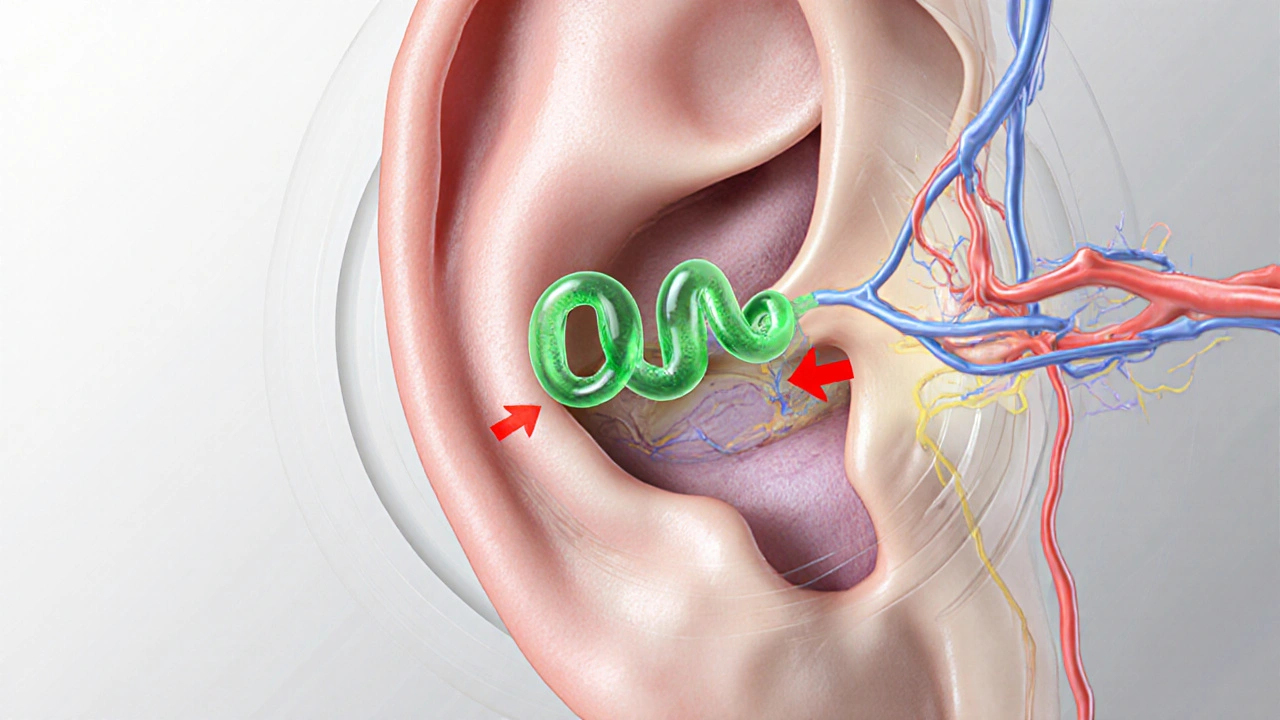

The medical term for ringing, buzzing, or hissing in the ears is tinnitus, a symptom rather than a disease. It can arise from anything that disrupts the auditory pathway - from earwax buildup to high‑frequency noise exposure. In the context of Lyme disease, the culprit is usually inflammation of the cranial nerves or inner‑ear structures caused by the spirochete’s invasion of nervous tissue.

How Lyme disease triggers tinnitus

When Borrelia burgdorferi reaches the central nervous system, doctors call it neuroborreliosis. The bacterium can cause:

- Inflammation of the eighth cranial nerve (vestibulocochlear nerve), which carries sound signals to the brain.

- Fluid imbalances in the inner ear, leading to abnormal firing of hair cells.

- Generalized brain inflammation that alters how auditory signals are processed.

Any of these mechanisms can produce the perception of sound when none exists - that’s tinnitus.

Other neurological signs that often travel with tinnitus

Because the nervous system is a common target during the early disseminated phase, patients may notice a mix of symptoms, such as:

- Facial weakness (Bell’s palsy) on one side.

- Severe headaches or neck stiffness that feel like meningitis.

- Memory fog, concentration trouble, or mood swings.

- Sharp shooting pains in the arms or legs (radiculitis).

If you experience a combination of these signs alongside a recent tick bite, the likelihood of Lyme jumps considerably.

When to suspect Lyme disease instead of other tinnitus causes

Most people think of loud concerts or ear infections when they hear ringing. To separate Lyme‑related tinnitus from the crowd, ask yourself:

- Did I spend time in tick‑infested areas (wooded trails, grassy fields) in the past few weeks?

- Is the ringing accompanied by flu‑like symptoms (fever, chills, muscle aches) or a rash?

- Do I have any facial weakness, headaches, or joint pain that appeared at the same time?

- Is the tinnitus persistent, fluctuating, or worsening despite removing earwax or avoiding loud noises?

A positive answer to the first three questions should prompt a medical evaluation for Lyme disease.

How doctors diagnose Lyme‑related tinnitus

Diagnosis follows a two‑tier approach recommended by the CDC:

- Initial screening: An enzyme‑linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) looks for antibodies against Borrelia burgdorferi. A negative result usually rules out Lyme, but early infection can yield false‑negatives.

- Confirmatory test: If ELISA is positive or clinical suspicion is high, a Western blot detects specific IgM and IgG bands. Presence of multiple bands confirms infection.

In cases with neurological involvement, doctors may also order a lumbar puncture to examine cerebrospinal fluid for elevated white‑blood‑cell counts or intrathecal antibody production.

Treatment - can antibiotics stop the ringing?

Most clinicians start with oral doxycycline (or amoxicillin for those who can’t take doxy). A typical course lasts 14-21 days for early disseminated disease. Studies show that up to 80% of patients experience resolution of tinnitus within weeks of beginning antibiotics, provided treatment starts early.

If symptoms persist after the first round, a second, longer course or intravenous ceftriaxone may be recommended. Physical therapy and audiology referrals help manage lingering auditory issues, while some patients benefit from short‑term corticosteroids to reduce nerve swelling.

Lyme disease isn’t a death sentence; timely therapy usually restores normal hearing. However, delayed treatment can lead to chronic tinnitus that may require long‑term management.

Preventing tick bites - the simplest way to keep tinnitus away

Because the infection begins with a bite, avoiding ticks is the most effective prevention strategy:

- Wear long sleeves and pants when hiking in tall grass; tuck pants into socks.

- Apply EPA‑registered repellents containing DEET, picaridin, or oil of lemon eucalyptus.

- Check your body, pets, and gear for attached ticks within 30minutes of leaving the outdoors.

- Remove any attached tick with fine‑tipped tweezers, grasping as close to the skin as possible and pulling upward steadily.

- Consider a single dose of doxycycline in late spring if you live in a high‑risk area (consult a doctor first).

Even in regions like NewZealand where endemic Lyme isn’t established, travelers to endemic zones should follow these precautions.

Quick checklist for anyone hearing a ring after a tick bite

- Note the date and location of the bite.

- Record any accompanying symptoms: rash, fever, headache, joint pain.

- Seek medical care within 2weeks if tinnitus lasts more than a few days.

- Ask for two‑tier serologic testing and, if needed, a lumbar puncture.

- Begin the prescribed antibiotic regimen promptly and finish the full course.

- Follow up with your clinician if ringing persists after treatment.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can tinnitus be the only symptom of Lyme disease?

Yes, especially in the early disseminated stage. However, most patients also report fatigue, headache, or a subtle rash. A thorough exposure history helps doctors decide when to test.

How long does it take for tinnitus to improve after antibiotics?

Many people notice improvement within a few days to two weeks. Full resolution can take up to six weeks, depending on how quickly treatment began.

Is a negative ELISA test enough to rule out Lyme?

Not always. Early infection may not have generated enough antibodies. If clinical suspicion is high, doctors may still order a Western blot or repeat testing after a week.

Should I take a preventive dose of doxycycline before hiking?

In some high‑risk areas, a single weekly dose of doxycycline during tick season is recommended for adults. Talk to a healthcare provider to weigh benefits and possible side effects.

Can Lyme disease cause permanent hearing loss?

Permanent loss is rare if treatment starts early. Chronic infection or delayed therapy can lead to lasting auditory damage, but most patients recover with antibiotics and supportive care.

johnson mose

Just trekked through the Adirondacks last weekend and came back with an annoying high‑pitched buzz that wouldn't quit – totally threw me off during my morning coffee ritual. I did some digging and realized that tinnitus can actually be a sneaky early warning sign of Lyme disease, especially when you’ve been in tick‑dense woods. The inflammation of the vestibulocochlear nerve sounds like something straight out of a horror flick, but it’s real science. If you ever notice that ringing paired with a fever or that classic bull’s‑eye rash, don’t brush it off as earwax. Early antibiotics can be a game‑changer, turning that constant hiss into silence. And trust me, the relief after a proper course of doxycycline feels like stepping out of a fog into bright sunlight. Stay vigilant, check your skin, and if the ringing persists, get tested before it spirals.

Charmaine De Castro

Great rundown on how Lyme can affect the auditory system. I appreciate the clear checklist – especially the part about noting tick exposure dates. It makes it easier for anyone to present a concise history to their doctor. If you’re dealing with tinnitus and have been hiking, definitely bring this info to your appointment.

Mark Mendoza

👍 Spot on, Charmaine! Adding to that, many labs now offer rapid ELISA results, so you don’t have to wait weeks to know if you’re in the clear. If the test comes back negative but symptoms linger, a repeat test in a week can catch early seroconversion.

Dan Tourangeau

Short and sweet – keep those pants tucked in and use DEET. Prevention beats treatment every time.

Bernard Valentinetti

Indeed-while the auditory nerve’s susceptibility to spirochetes is well‑documented, one must also consider the myriad of confounding otologic conditions; thus, a differential diagnosis remains paramount-especially when the clinical picture is clouded by concurrent ototoxic medication usage.

Kenneth Obukwelu

💡 Bernard makes a solid point, but let’s not forget that early neuroborreliosis can masquerade as simple ear congestion. A thorough neurologic exam, maybe even an MRI if doubts persist, can tip the scales toward the right diagnosis.

Josephine hellen

When I first heard about tinnitus being linked to Lyme disease, I was skeptical. I’d always associated ringing ears with loud concerts, earbuds, or age‑related hearing loss. However, after a summer camping trip in Connecticut, I noticed a subtle humming that grew louder over a few days. Alongside a mild fever and an odd rash on my thigh, I started Googling symptoms and landed on this comprehensive article. The explanation about the spirochete invading the eighth cranial nerve really clarified why my ears were buzzing. I promptly visited my physician, who ordered the two‑tier serologic testing. The ELISA came back borderline, but because my clinical picture was convincing, we proceeded to a Western blot, which confirmed early disseminated Lyme. I was prescribed a 21‑day course of doxycycline. Within ten days of finishing the antibiotics, the tinnitus faded dramatically, leaving only a faint echo that disappeared after a couple of weeks. My experience reinforced the article’s point: early detection and treatment are crucial. It also highlighted the importance of keeping a symptom diary – noting the exact dates of tick exposure, rash appearance, and any neurological signs can streamline the diagnostic process. Moreover, the piece’s prevention tips are invaluable; I now wear long sleeves, apply picaridin, and perform tick checks within 30 minutes of leaving the woods. I’ve shared this knowledge with my hiking group, emphasizing that a simple ring in the ears could be a far more serious warning sign. In sum, this article offers a lifeline for anyone who might dismiss tinnitus as an annoyance. It’s a reminder that our bodies often communicate through subtle cues, and paying attention can save us from prolonged suffering.

Ria M

The dramatics of a buzzing ear echoing through the forest are almost poetic, yet the underlying pathology is starkly clinical. I love how the author blends narrative with precise medical facts, making the piece both engaging and actionable. Remember, a tick bite can be silent, but the cascade it triggers is anything but.

Michelle Tran

😀 Absolutely, Ria – the blend of storytelling and hard data makes the warning hit home.

Caleb Ferguson

Thanks for the thorough breakdown. For anyone unsure about the testing process, ask your doctor about the possibility of a lumbar puncture if neurological symptoms are prominent; it can provide definitive evidence of neuroborreliosis.

Delilah Jones

While lumbar punctures sound scary, they’re often the clincher for confirming infection when serology is ambiguous. Don’t let fear delay diagnostic clarity.

Pastor Ken Kook

Cool info – I’ll definitely add tick checks to my post‑hike routine. 😎

Jennifer Harris

Interesting.

Northern Lass

While the exposition is admirably comprehensive, one must query the reliance on serologic assays given their documented sensitivity limitations in early infection; perhaps the discourse should underscore the necessity of repeat testing or adjunctive polymerase chain reaction modalities to mitigate false‑negative outcomes.

Johanna Sinisalo

I agree with the suggestion to consider repeat testing. In clinical practice, a second ELISA after a week often captures seroconversion that was missed initially.

OKORIE JOSEPH

Yo this whole tick thing is overhyped stop freaking out about a little buzz in your ears it’s probably just earwax

Lucy Pittendreigh

Ignore that nonsense the data is clear – don’t let laziness kill you

Justin Ornellas

From a linguistic standpoint, the article excels in balancing technical terminology with layperson accessibility; however, the occasional over‑use of passive constructions could be refined to enhance readability without sacrificing precision.

JOJO Yang

yeah but it’s still a good read i think

Gary Giang

Thanks for the thorough overview. I’ll keep the checklist handy for future hikes.