When someone with Parkinson’s disease starts seeing things that aren’t there-voices, shadows, people in the room-it’s terrifying. Not just for them, but for their family. Psychosis in Parkinson’s isn’t rare. It affects about 1 in 4 people with the condition, and it’s one of the top reasons they end up in the hospital. The obvious solution? An antipsychotic. But here’s the cruel twist: the very drugs meant to calm the mind can make the body shut down.

The Paradox of Treating Psychosis in Parkinson’s

Parkinson’s disease is caused by the slow death of dopamine-producing neurons in the brain. Dopamine isn’t just about mood-it’s the chemical that lets your muscles move smoothly. Without enough of it, you get tremors, stiffness, slow movements, and trouble balancing. That’s the motor side of Parkinson’s. Now, psychosis in Parkinson’s-called PDP-comes from a different part of the brain. It’s linked to changes in serotonin and other chemicals, not just dopamine. So doctors reach for antipsychotics, drugs designed to block dopamine receptors and quiet hallucinations. But here’s the problem: those same receptors are needed for movement. Block them too much, and the tremors get worse. The stiffness tightens. Walking becomes harder. Some people go from being able to walk with a cane to needing a wheelchair in weeks. This isn’t theoretical. It’s been documented since the 1970s. Back then, doctors started giving haloperidol (Haldol) to Parkinson’s patients with psychosis. Within days, many couldn’t move. Their symptoms spiked. It wasn’t the disease getting worse-it was the drug.Which Antipsychotics Make Things Worse?

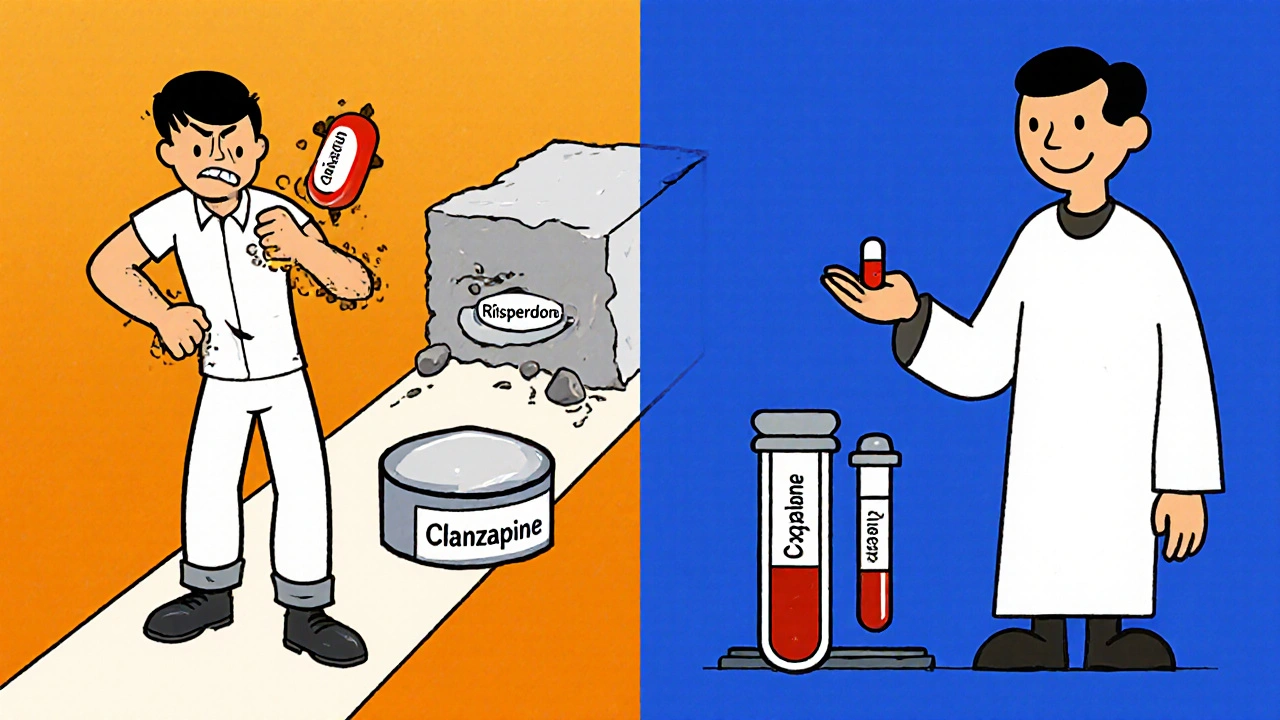

Not all antipsychotics are the same. They vary wildly in how strongly they block dopamine, especially the D2 receptor. The more they block, the worse the motor symptoms become. Haloperidol is the worst offender. It latches onto D2 receptors with nearly 100% efficiency. At standard doses, it causes severe parkinsonism in 70-80% of patients. Even tiny doses-0.25 mg a day-can trigger stiffness or freezing. The Parkinson’s Foundation says: never use it. Fluphenazine and chlorpromazine are almost as bad. They’re first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs), built on the same old model: block dopamine, stop psychosis. They’re like using a sledgehammer to fix a watch. Even some second-generation drugs aren’t safe. Risperidone (Risperdal) was once thought to be gentler. But studies show it makes motor symptoms worse in nearly all Parkinson’s patients. One 2005 trial found patients on risperidone had a 7.2-point increase on the motor scale (UPDRS-III). That’s a massive drop in function-enough to lose independence. And here’s the kicker: risperidone also increases the risk of death in Parkinson’s patients by more than double. Olanzapine (Zyprexa) has a similar story. In one study, 75% of patients saw their hallucinations improve-but 75% also got worse at walking and moving. Half had dramatic declines. Only one person out of twelve stayed on it.The Two Safer Options

There are two antipsychotics that don’t trash motor function. And they’re not even close to the same as the others. Clozapine (Clozaril) is the gold standard. It blocks dopamine just enough to reduce hallucinations without crushing movement. In clinical trials, it cuts psychosis by nearly half-without worsening UPDRS scores. The FDA approved it for Parkinson’s psychosis in 2016. But it’s not simple. It can cause agranulocytosis-a dangerous drop in white blood cells. That’s why patients need weekly blood tests. If the count falls below 1,500, it’s stopped immediately. Still, for many, it’s the only option that works without breaking their mobility. Quetiapine (Seroquel) is used off-label. It has weaker dopamine blocking and works more on serotonin. Many doctors start here because it’s easier to monitor than clozapine. Studies show it helps psychosis in about half of patients. But there’s controversy. One 2017 trial found quetiapine worked no better than a sugar pill. Still, in real-world practice, many patients and families report improvement-especially at low doses (12.5-25 mg at night).

What About Newer Drugs?

In 2022, the FDA approved pimavanserin (Nuplazid). It’s the first antipsychotic for Parkinson’s that doesn’t touch dopamine at all. Instead, it targets serotonin 5-HT2A receptors. In trials, it improved hallucinations without making movement worse. That’s huge. But it’s not perfect. Post-marketing data showed a 1.7-fold higher risk of death. The FDA slapped on a black box warning. Still, for patients who can’t tolerate clozapine or quetiapine, it’s an option. Now, a new drug called lumateperone is in phase III trials. Early results suggest it reduces psychosis without motor side effects. Final data is expected in 2024. If it holds up, it could change everything.The Right Way to Handle Psychosis

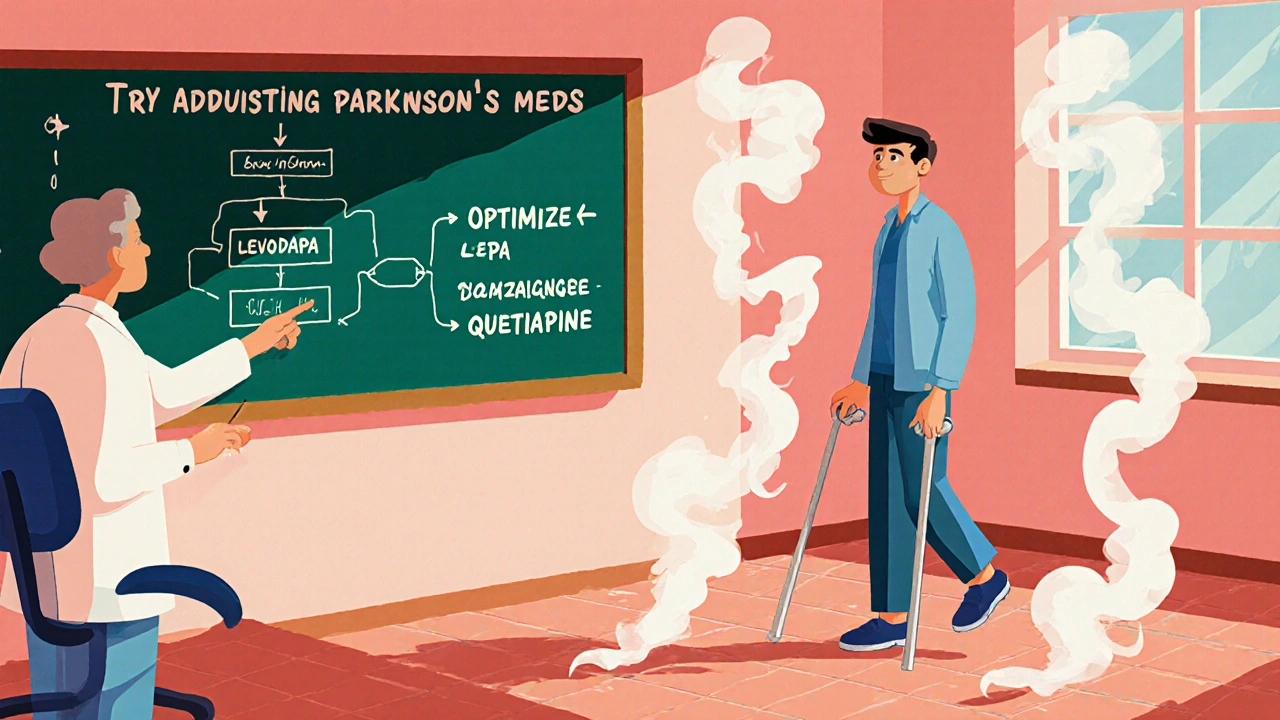

The biggest mistake? Jumping straight to antipsychotics. The Parkinson’s Foundation’s 2023 guidelines say: try everything else first. Step one: Review all medications. Many Parkinson’s drugs-like dopamine agonists, anticholinergics, or even some antidepressants-can trigger psychosis. Reducing or stopping them often clears up hallucinations. One 2018 study found that 62% of patients saw their psychosis vanish just by adjusting their Parkinson’s meds. Step two: If that doesn’t work, optimize levodopa. Too much can cause hallucinations. Too little can make psychosis worse. Finding the sweet spot takes time, but it’s worth it. Step three: Only then, if psychosis is still severe and dangerous, consider clozapine or quetiapine. Start low. Go slow. Monitor motor function every two weeks. If UPDRS scores jump by more than 30%, stop the drug.

Why This Matters

This isn’t just about symptoms. It’s about quality of life. A person with Parkinson’s who can’t walk, talk, or feed themselves because of a bad drug choice isn’t just suffering-they’re losing their dignity. And it’s preventable. Doctors who don’t know this can accidentally destroy a patient’s mobility. Families who don’t know this might push for a quick fix-thinking, “If it helps the voices, it must be worth it.” But the cost is too high. The truth? Treating psychosis in Parkinson’s isn’t about picking the strongest antipsychotic. It’s about picking the one that leaves movement intact. That’s the only real win.What You Can Do

If you or someone you care for has Parkinson’s and psychosis:- Ask the neurologist: “Are we sure we’ve tried adjusting Parkinson’s meds first?”

- Ask: “Is this antipsychotic known to worsen movement?” If they say haloperidol, risperidone, or olanzapine-push back.

- Request a UPDRS motor score before and after any new drug.

- If clozapine is suggested, ask about blood monitoring requirements.

- Don’t accept “it’s just part of the disease.” Psychosis can be managed without breaking mobility.

The goal isn’t to eliminate every hallucination. It’s to keep the person alive, safe, and able to move. That’s the real measure of success.

Erika Sta. Maria

so like... if your grandma sees the dead uncle who died in 1998 walking through the kitchen, but then she can't hold her coffee cup because her hands are shaking like a leaf in a hurricane... is that progress? or just swapping one nightmare for another? i mean, we're not treating the disease here, we're just playing russian roulette with her dignity.

Nikhil Purohit

really appreciate this breakdown. i’ve seen this happen firsthand-my uncle was on risperidone for 3 weeks and went from walking his dog daily to needing a walker. the docs kept saying 'it’s just Parkinson’s getting worse.' no, it was the drug. took 6 months to get them to switch to quetiapine. he’s still hallucinating a bit, but now he can actually sit in his chair without falling over. small wins.

Debanjan Banerjee

Let me clarify the pharmacology here for those misunderstanding the mechanism: clozapine’s low D2 affinity and high 5-HT2A antagonism is precisely why it avoids extrapyramidal side effects. Risperidone, despite being labeled 'atypical,' still has sufficient D2 occupancy (>70%) to induce parkinsonism. The 2005 UPDRS-III increase of 7.2 points is clinically catastrophic-it translates to a loss of functional independence. Pimavanserin’s 5-HT2A inverse agonism is the only truly dopamine-sparing approach currently approved. Lumateperone’s dual serotonin-dopamine modulation shows promise, but its binding kinetics are not yet fully characterized in PD populations. Always monitor absolute neutrophil count with clozapine-agranulocytosis is not a theoretical risk.

Shawn Sakura

you guys are doing such important work sharing this. my mom had this exact thing happen. they put her on haloperidol and she couldn't stand up for 3 weeks. i cried so hard. thank you for making this so clear. please keep fighting for better care.

Paula Jane Butterfield

as someone who grew up watching my abuela battle Parkinson’s and then psychosis-this hits home. we were told 'it's just part of aging' by three different doctors. never once did anyone mention adjusting her levodopa first. by the time we got to clozapine, she’d lost 18 months of mobility. if you’re reading this and you’re a caregiver-ask for the UPDRS. demand it. don’t let them rush you into a drug that steals movement.

Simone Wood

let me tell you what they don’t want you to know-big pharma doesn’t want you using clozapine because it’s cheap, generic, and requires blood draws. they’d rather sell you $12,000-a-year pimavanserin while your loved one sits in a wheelchair. it’s not medicine-it’s profit. and the FDA? they’re just the bouncer letting the bad drugs in the club.

Swati Jain

so let me get this straight-we have a drug that doesn’t mess with dopamine (pimavanserin) but it kills people faster? and the one that doesn’t kill you (clozapine) makes you check your blood every week like you’re in a Soviet labor camp? brilliant. just brilliant. we’re treating psychosis by turning patients into medical lab rats. congrats, science.

Florian Moser

my dad’s on quetiapine now-25mg at night. he still sees his dead brother, but he can feed himself again. that’s enough for us. i don’t need him to be 'cured'-i need him to be here, awake, and holding my hand. thank you for writing this. it’s the kind of info that saves lives, not just symptoms.

jim cerqua

THIS IS A MASSACRE. THEY’RE KILLING PEOPLE WITH MEDICINE. HALOPERIDOL IS A WAR CRIME AGAINST THE ELDERLY. I’VE SEEN IT-GRANDMAS TURNED INTO STATUES, TALKING TO GHOSTS WHILE THEIR HANDS LOCK UP LIKE ROBOTS. AND THE DOCTORS? THEY’RE TOO LAZY TO READ THE 50-YEAR-LONG LITERATURE. THEY WANT A QUICK FIX. THEY WANT A PILL. THEY DON’T WANT TO DO THE WORK. THIS IS NOT MEDICINE. THIS IS NEGLIGENCE WITH A WHITE COAT.

Donald Frantz

what’s the actual mortality rate for clozapine vs. pimavanserin in PD patients? the black box warning on pimavanserin sounds scary, but is it statistically significant compared to the 2x death risk with risperidone? i need hard numbers, not anecdotes. also-how many patients actually get monitored properly for agranulocytosis? my guess: less than 30%.

Sammy Williams

my wife’s neurologist just prescribed quetiapine. we’re starting at 12.5mg. fingers crossed. i just want her to sleep without screaming at the shadows. if she can still hug me without her arms shaking like she’s got the chills… i’ll take it.

Julia Strothers

who funded this article? the NIH? big pharma? because pimavanserin is made by Acadia-whose CEO made $120M last year. and now they’re pushing it as the 'safe' option? sure. while clozapine sits in the basement, ignored because it’s too cheap. this isn’t science-it’s a cash grab wrapped in a white coat.

Steve Harris

thank you for this. i’m a nurse in a long-term care unit, and I’ve seen this happen too many times. we had a patient on olanzapine who went from walking to the dining hall to bedbound in 10 days. We switched to quetiapine-slowly, with weekly UPDRS checks-and within 3 weeks, she was back to her crossword puzzles. It’s not magic. It’s just… careful. And that’s what we’re missing. Care. Not just pills.