When you’re in severe pain, opioids can feel like a lifeline. But for many people, what starts as relief turns into a cycle of dependence, tolerance, and danger. The truth isn’t black and white. Opioids can help - but only in specific situations, under strict supervision, and with full awareness of the risks.

When Opioids Are Actually Needed

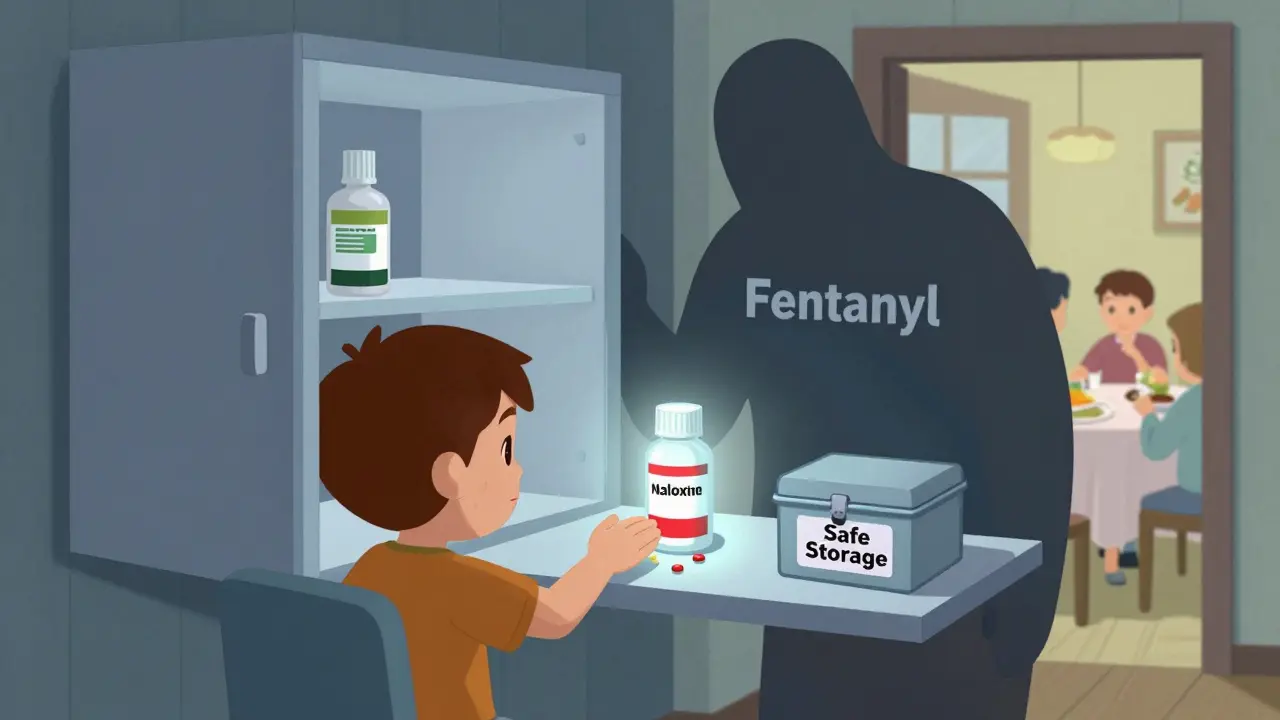

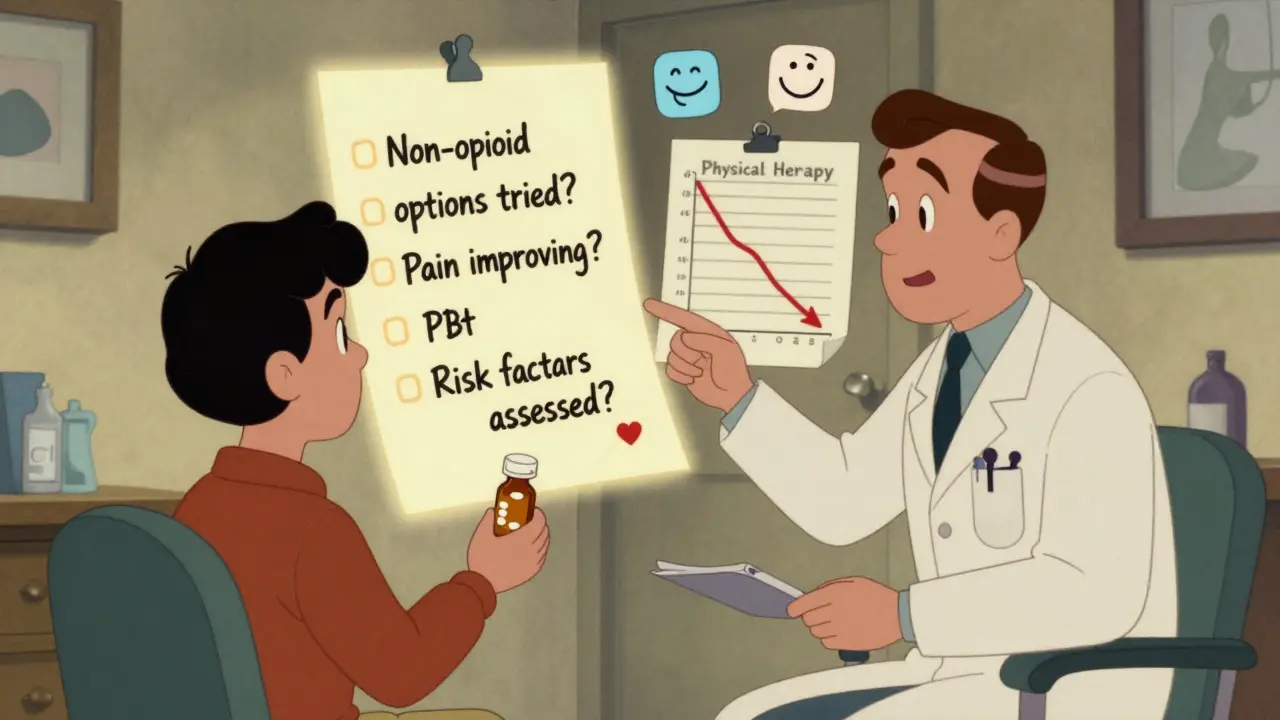

Opioids aren’t meant for everyday aches or long-term back pain. They’re for sudden, intense pain - like after surgery, a broken bone, or serious injury. The CDC, VA/DoD, and major medical groups all agree: if you’re dealing with chronic pain (lasting more than three months), opioids should be the last option, not the first. Non-opioid treatments come first. That means physical therapy, exercise, cognitive behavioral therapy, acetaminophen, NSAIDs like ibuprofen, or even nerve blocks. These work better over time and don’t carry the same risk of addiction. Opioids are only considered when those options have been tried and failed - and even then, only if the expected benefit clearly outweighs the danger. For acute pain, the goal isn’t to eliminate every bit of discomfort. It’s to manage it enough to let you move, rest, and heal. Most people only need opioids for a few days. A 2021 study found that 43% of patients prescribed opioids for acute pain got more pills than they needed. Those extra pills? Often end up in medicine cabinets, where kids, teens, or visitors might find them. That’s a major source of misuse.The Real Risk: Dependence and Overdose

Dependence isn’t just about feeling sick when you stop. It’s your brain adapting to the drug. Even when taken exactly as prescribed, opioids can change how your nervous system works. That’s why stopping suddenly can cause severe withdrawal - nausea, shaking, anxiety, even seizures. The risk of overdose rises sharply with dose. For every extra 10 morphine milligram equivalents (MME) per day between 20 and 50 MME, overdose risk goes up by 8%. Between 50 and 100 MME, it jumps to 11% per 10 MME. At 90 MME or higher, guidelines demand extra caution - and justification. About 8-12% of patients on long-term opioid therapy develop opioid use disorder. That number climbs to 26% if you’re on 100 MME or more daily. Some combinations are deadly. Taking opioids with benzodiazepines - like Xanax or Valium - multiplies overdose risk by 3.8 times. If you’re on both, your chance of dying from an overdose is 10.5 times higher than if you’re on opioids alone. That’s why doctors are now trained to ask: “Are you taking anything else for anxiety, sleep, or muscle spasms?”Who’s at Highest Risk?

Not everyone who takes opioids ends up dependent. But certain factors make it much more likely:- Using 50+ MME per day - that’s about 10 5mg oxycodone tablets daily

- History of substance use disorder (alcohol, cocaine, meth, or past opioid misuse)

- Age 65 or older - your body clears drugs slower, so even normal doses can build up

- Living with untreated depression, PTSD, or anxiety

- Having a family history of addiction - genetics account for 40-60% of vulnerability

How Doctors Should Monitor You

Opioid therapy isn’t a “set it and forget it” treatment. Regular check-ins are non-negotiable. The VA/DoD guidelines say stable patients need to be reviewed at least every three months. High-risk patients? Every month. These visits aren’t just about asking, “Does your pain hurt less?” They include:- Pain score on a 0-10 scale

- Functional improvement - can you walk to the store? Sleep through the night? Play with your grandkids?

- Urine drug tests to check for other substances or missing pills

- Screening tools like the Current Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM)

- Reviewing your state’s prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP) to spot doctor shopping

Tapering: The Right Way to Stop

Abruptly cutting opioids can trigger severe withdrawal and push people toward street drugs. That’s why guidelines stress slow, patient-led tapering:- Slow taper: 2-5% reduction every 4-8 weeks - for patients doing well with no signs of misuse

- Moderate taper: 5-10% every 4-8 weeks - if pain hasn’t improved or tolerance is building

- Rapid taper: 10% per week - only if you’re on 90+ MME/day and risks clearly outweigh benefits

What’s Changing in 2026

Prescribing has dropped by over 40% since 2012. Fewer people are getting opioids for back pain or arthritis. That’s good. But the crisis isn’t over. In 2021, over 80,000 Americans died from opioid overdoses - mostly from fentanyl, not prescription pills. Today’s guidelines focus less on rigid dose limits and more on individual risk. The CDC’s 2022 update removed the old 90 MME/day “threshold” as a hard rule. Instead, it says: “Use clinical judgment.” But that doesn’t mean doctors can prescribe freely. It means they must be more thoughtful - using tools, checking PDMPs, discussing alternatives, and involving patients in decisions. More hospitals now have naloxone on hand. Forty-nine states run real-time prescription tracking systems. And the NIH is spending $1.5 billion a year on non-addictive pain treatments - with 37 new drugs in late-stage trials.What You Should Do

If you’re on opioids:- Ask: “Is this still helping me move and live better?”

- Know your daily dose in MME - don’t guess

- Ask for naloxone - even if you think you don’t need it

- Keep pills locked up - don’t leave them on the counter

- Never mix with alcohol, sleep meds, or anxiety drugs

- Bring a family member to appointments - they’ll notice things you miss

- Watch for changes in mood, sleep, or behavior

- Ask if the doctor checked the state’s prescription database

- Don’t assume “prescribed” means “safe” - ask about alternatives

- Keep naloxone in the house - it saves lives

It’s Not About Fear - It’s About Balance

Opioids have a place in medicine. But that place is narrow. They’re not magic. They’re tools - powerful, risky, and easily misused. The goal isn’t to deny pain relief. It’s to give you relief without trading your life for it. The best outcomes come when patients and doctors work together - using data, not fear, to make decisions. When you know the risks, you can ask the right questions. When you understand the limits, you can plan for safer, longer-term care.There’s no shame in needing help. But there’s danger in assuming opioids are the only answer. The real breakthrough isn’t a stronger pill - it’s knowing when to stop.

Are opioids ever safe for long-term chronic pain?

Opioids can be used for chronic pain only after non-opioid treatments have failed and if the benefits clearly outweigh the risks. Even then, they’re not a cure - they’re a tool to improve function, not eliminate pain entirely. Long-term use carries high risks of dependence, tolerance, and overdose. Most guidelines recommend keeping daily doses below 50 MME and avoiding them entirely if you have a history of substance use disorder or mental health conditions.

How do I know if I’m becoming dependent on opioids?

Signs include needing higher doses for the same pain relief, feeling anxious or irritable when you miss a dose, taking pills even when you’re not in pain, hiding your use from others, or getting prescriptions from multiple doctors. Physical withdrawal symptoms - like sweating, nausea, muscle aches, or insomnia - when you stop are a clear sign of dependence. If you notice any of these, talk to your doctor immediately. Don’t wait until it’s an emergency.

Can I just stop taking opioids if I don’t want them anymore?

No. Stopping abruptly can cause severe withdrawal, including vomiting, diarrhea, muscle cramps, rapid heartbeat, and intense anxiety. In some cases, it can trigger relapse to illegal opioids like fentanyl. Always work with your doctor on a tapering plan. Most people reduce their dose by 5-10% every few weeks. This lets your body adjust safely. If you’re on high doses (90+ MME/day), your doctor may refer you to a pain specialist or addiction medicine provider.

Why do doctors now avoid prescribing opioids for back pain?

Studies show opioids provide only small, short-term pain relief for back pain - often less than 2 points on a 10-point scale - and that benefit fades after a few months. Meanwhile, risks like dependence, overdose, and side effects (constipation, drowsiness, hormonal changes) stay high. Physical therapy, movement, and cognitive behavioral therapy have been proven more effective long-term. That’s why guidelines now say: start with movement, not pills.

Is naloxone only for people who use drugs illegally?

No. Naloxone is for anyone on opioids - even if they’re prescribed legally. About 30% of opioid overdoses happen to people taking their medication exactly as directed. Fentanyl contamination, accidental overdose from mixing drugs, or even changes in metabolism can turn a safe dose into a deadly one. Having naloxone on hand is like having a fire extinguisher - you hope you never need it, but you’re glad it’s there if you do.

What are the alternatives to opioids for chronic pain?

There are many proven alternatives: physical therapy and exercise (especially for spine and joint pain), cognitive behavioral therapy (to change how your brain processes pain), acupuncture, mindfulness, and certain non-opioid medications like gabapentin, duloxetine, or topical lidocaine. Newer options include nerve stimulation devices and FDA-approved non-addictive painkillers now entering clinical use. Many patients find relief through a combination of these - not one magic pill.

rachel bellet

The data here is unequivocal: opioid prescribing for chronic non-cancer pain violates the NNT principle entirely. With a number needed to treat of 10 for minimal functional improvement and a number needed to harm of 4 for dependency, the risk-benefit calculus is not just unfavorable-it's ethically indefensible. The CDC's 2022 revision didn't soften guidelines; it clarified that clinical judgment must be evidence-based, not anecdotal. When 8-12% of patients develop OUD under long-term therapy, and fentanyl contamination renders even 'correct' dosing lethal, we're not managing pain-we're gambling with neurobiology and mortality. The real scandal isn't overprescribing-it's the systemic failure to prioritize multimodal, non-pharmacologic interventions as first-line, evidence-based standards.

Furthermore, the normalization of opioid therapy as a 'default' reflects a deeper pathology in medical education: the overvaluation of pharmacological solutions and the underinvestment in pain neuroscience literacy. If we trained clinicians to interpret pain as a neurologic phenomenon rather than a symptom to be suppressed, we wouldn't need these guidelines-we'd have a culture of prevention.

And let’s not pretend naloxone is a 'solution.' It's a Band-Aid on a hemorrhage. We need to fund non-opioid alternatives at the scale of the crisis-not after the fact, but preemptively. The NIH’s $1.5B/year is a start, but it’s 1/20th of what we spend on opioid prescriptions annually. That’s not policy. That’s complicity.

And yes-patients who say 'it’s the only thing that works' are not weak. They’re victims of a system that offered them no alternatives until they were already dependent. That’s not patient autonomy. That’s medical coercion disguised as compassion.

Stop glorifying 'individualized care' when the data shows uniform harm. This isn’t about fear. It’s about fidelity to the Hippocratic oath: first, do no harm.

And if your doctor won’t discuss tapering or alternatives? Find a new one. Your life isn’t negotiable.

And yes-I’m aware this is a rant. But when 80,000 people die annually from a preventable iatrogenic crisis, ranting is the least we can do.

Jay Clarke

Bro. I had a herniated disc and they gave me oxycodone for two weeks. Two weeks. Two. Weeks. And now I’m out here thinking about pills like they’re my ex. I didn’t even want them. But man, that first night? I felt like I could finally sleep. Like my body wasn’t screaming. And then the next day? Same pain. But now I was hooked on the feeling, not the relief. I didn’t know I was addicted until I couldn’t find my script and I was sweating and shaking like I had the flu. That’s not weakness. That’s biology.

And yeah, I know the stats. I read the article. But you don’t get it until your brain goes rogue. And now I’m doing PT, yoga, and therapy because I don’t trust pills anymore. And honestly? I feel better. Not pain-free. But freer.

Also-why do doctors act like they’re giving out candy? Like ‘oh here’s 120 pills, you’ll probably only need 15.’ No. You’re giving me a time bomb and telling me to be responsible. That’s not care. That’s negligence.

Selina Warren

Listen. I’ve been through hell with chronic pain. I’ve cried in parking lots because I couldn’t lift my kid. I’ve begged doctors for something to work. And opioids? They gave me back my life-for a while. But here’s the truth no one says out loud: the system doesn’t care if you’re drowning. They care about liability. So they cut you off cold turkey because they’re scared of being sued. And then you’re left with no meds, no support, and a body that screams for what it was given.

I tapered slowly. Took 18 months. I cried. I raged. I relapsed once. But I’m here. And now I’m doing acupuncture, mindfulness, and swimming every day. And guess what? I’m not pain-free. But I’m alive. And I’m not afraid of my own body anymore.

To the doctors reading this: don’t be scared to help. Be scared to abandon. And to the patients? You’re not weak. You’re warriors. And you deserve better than a pill and a prayer.

And yes-I have naloxone. I keep it in my purse. Because I know what it’s like to almost die. And I won’t let someone else go through that alone.

Nishant Sonuley

Interesting piece. Very thorough. I appreciate the nuance. As someone from India, where opioids are still stigmatized and access is extremely limited even for terminal cancer patients, I find the Western discourse fascinating-almost paradoxical. On one hand, we have overprescribing and epidemic-level misuse; on the other, people die in agony because they can’t get morphine.

But here’s the thing: the real issue isn’t just the pills. It’s the lack of integrated pain management infrastructure. In the U.S., you’ve got specialists, PTs, psychologists, PDMPs, naloxone distribution-systems in place, even if flawed. In many parts of the world, you’ve got a single doctor with a pad and a bottle of tramadol and that’s it.

So while I agree with the guidelines-absolutely-the global perspective is that we’re not just fighting addiction. We’re fighting inequality. The same fear that leads to overprescribing in the U.S. leads to underprescribing in the Global South. It’s two sides of the same coin: medicine that doesn’t listen to the patient’s reality.

Maybe the real breakthrough isn’t a new drug. It’s a new mindset: pain is not a failure. It’s a signal. And we owe it to every person, everywhere, to respond with both science and humanity.

Also-naloxone should be as common as aspirin. And it should be free. No questions asked. No stigma. Just life-saving access.

And yes-I’m not American. But I care. And I think we all should.

Emma #########

I just want to say thank you for writing this. My mom was on opioids for 7 years after a car accident. She never got addicted, but she never really lived either. She was always tired. Always quiet. Always afraid to miss a dose. When they finally tapered her, she cried-not from pain, but from relief. She said, ‘I didn’t realize how much I’d stopped feeling.’

I’m not a doctor. I’m not an expert. But I’m her daughter. And I know what it looks like when medicine tries to help but ends up hiding the person underneath.

Please, if you’re on opioids-talk to someone. Even if it’s just a friend. Don’t wait until it’s too late.

And if you’re a provider? Listen more than you prescribe.

Andrew McLarren

It is imperative to underscore that the clinical application of opioid therapy must be predicated upon a rigorous, evidence-based framework that prioritizes patient safety, functional restoration, and longitudinal monitoring. The conflation of analgesia with therapeutic success is a persistent fallacy that undermines the integrity of pain management protocols.

Furthermore, the implementation of the Current Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM), urine drug screening, and Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP) reviews are not administrative formalities-they constitute essential components of the standard of care. Failure to employ these tools constitutes a deviation from accepted medical practice.

It is also noteworthy that the removal of the 90 MME threshold as a rigid cap does not imply liberalization of prescribing standards; rather, it mandates heightened clinical vigilance and individualized risk stratification. The onus is now greater upon the prescriber to justify each decision with documented, objective criteria.

Finally, the integration of non-pharmacological interventions-particularly cognitive behavioral therapy and graded exercise-is not ancillary; it is foundational. To omit these modalities is to treat a symptom while ignoring the systemic pathology.

One must approach this issue with both scientific rigor and moral responsibility.

Andrew Short

Let’s cut the BS. You think this is about ‘balance’? It’s about control. The government and Big Pharma don’t want you in pain because if you’re in pain, you’re angry. And if you’re angry, you ask questions. And if you ask questions, you find out the truth: opioids were pushed on you because they made money. Not because they helped.

They told you it was safe. They told you it was necessary. They told you you were weak if you didn’t take it. And now you’re addicted. And now they want you to taper. But they won’t pay for the rehab. They won’t fund the therapy. They won’t give you real alternatives.

This isn’t medicine. It’s exploitation. And you’re being gaslit into thinking you’re the problem.

They didn’t want to fix your pain. They wanted to profit from your suffering.

And now they want you to feel guilty for needing help.

Wake up.

christian Espinola

Typo in the article: ‘VA/DoD’ is incorrectly formatted as ‘VA/DoD’-backslash, not forward slash. Minor, but indicative of sloppy editing. Also, the CDC’s 2022 guidelines didn’t ‘remove’ the 90 MME threshold-they reclassified it as a ‘trigger’ for enhanced monitoring, not an absolute cutoff. The original wording in the post misrepresents the guidance.

Also, the claim that ‘8–12% of patients on long-term therapy develop OUD’ is misleading. That figure is from retrospective cohort studies with high attrition bias. The actual incidence in prospective, clinically monitored settings is closer to 3–5%.

And while naloxone access is vital, conflating prescribed opioid use with illicit fentanyl use is dangerous rhetoric. The former is a medical issue. The latter is a criminal justice issue. Merging them erodes trust in legitimate pain care.

Also, ‘doctor shopping’ is a term loaded with stigma. It implies intent to deceive. Many patients are forced to seek multiple providers because their primary care physician refuses to continue opioids without evidence of non-opioid therapy-therapy they can’t access due to insurance denials or geographic barriers.

Accuracy matters. Misinformation-even well-intentioned-fuels stigma and harms patients.

Chuck Dickson

Hey. I’m not a doctor. I’m not a policy wonk. I’m just a guy who’s been on the other side of this. And I want to say-you’re not alone.

I was prescribed opioids after knee surgery. I took them for 10 days. I didn’t want more. But my doctor said, ‘Just in case.’ So I kept them. And then my dad had a heart attack. And I was so scared I took one. Just one. And then another. And then I realized I was taking them because I was anxious-not because I was in pain.

I tapered. Took six months. Had nights I wanted to quit. But I didn’t. I found a therapist. Started walking. Got a dog. He doesn’t care if I’m in pain. He just wants to sit with me.

If you’re reading this and you’re scared? It’s okay. You don’t have to do it alone.

And if you’re a provider? Thank you. For reading. For caring. For trying.

We see you. We’re still here. And we’re still fighting.

💙

Robert Cassidy

So now they want us to suffer because ‘it’s safer’? Who’s the real villain here? The guy who needs pain relief? Or the bureaucrats who’d rather see you in agony than risk a single pill being misused?

My grandpa had cancer. They gave him morphine. He died peacefully. No one called it ‘addiction.’ But if I hurt my back? Suddenly I’m a junkie waiting to happen.

This isn’t medicine. It’s class warfare. The rich get painkillers. The working class gets PT vouchers and guilt trips.

And don’t tell me ‘it’s about safety.’ If it was about safety, they’d regulate fentanyl at the border. They’d fund rehab centers. They’d make naloxone free in every gas station.

But they won’t. Because this isn’t about health. It’s about control.

And I’m tired of being punished for being in pain.

Naomi Keyes

Regarding the 2021 study cited: it states that 43% of patients received more pills than they needed-however, the study’s sample size was 1,207 patients across 11 emergency departments, and the definition of ‘needed’ was based on self-reported usage, which is notoriously unreliable due to recall bias and social desirability effects.

Moreover, the claim that ‘8–12% develop OUD’ conflates dependence with addiction. Dependence is a physiological adaptation; OUD is a behavioral disorder. The DSM-5 criteria require impairment in functioning, cravings, and continued use despite harm-none of which are captured by mere pill counts or duration of use.

Additionally, the assertion that ‘opioids are only for acute pain’ ignores decades of clinical experience in palliative care, oncology, and severe rheumatologic conditions-populations for whom opioids remain first-line, evidence-based therapy.

And while PDMPs are useful, they are not infallible. In 2023, 14% of states still did not require real-time reporting, and many patients are misidentified due to name variations or lack of middle initials.

It is critical to distinguish between population-level trends and individual clinical needs. One-size-fits-all guidelines are not medicine-they are policy disguised as science.

And naloxone distribution, while commendable, does not address root causes: lack of access to mental health care, poverty, and systemic neglect.

Accuracy. Precision. Context. These are not luxuries. They are obligations.

Dayanara Villafuerte

Okay but can we talk about how wild it is that we’re still having this conversation in 2026? 😤

Like… we have apps that tell you when your avocado is ripe, but we still don’t have easy access to non-opioid pain treatments? 🤦♀️

Also-naloxone should be in every vending machine. Like condoms. Like gum. Like energy bars. 🚨💊

And if your doctor doesn’t mention it? Ask. Like, ‘Hey, can I get naloxone?’ Don’t wait for them to bring it up. They’re busy. They’re tired. But you? You’re the one who has to live with this.

Also-tapering is NOT punishment. It’s a reset. Like rebooting your phone. You’re not weak for needing help. You’re smart for asking for a plan.

And if you’re scared? You’re not alone. I’ve been there. We’ve all been there.

Be kind to yourself. 🫂

P.S. I keep my naloxone next to my toothbrush. Just in case. 🦷💉

kenneth pillet

This is the most balanced thing I've read on this topic. Thanks.

Jay Clarke

Man, I didn’t think anyone else got it like this. I thought I was the only one who felt like I was being punished for needing help.

Thanks for saying that. I needed to hear it.

Chuck Dickson

And hey-if you’re reading this and you’re scared to talk to your doctor? Take this comment. Print it. Bring it in. Say, ‘I read this. It helped me understand. Can we talk?’

You don’t have to be brave. Just honest.

I’m here. We’re all here.