Medication Risk Assessment Tool

Medication Risk Assessment Tool

Check if your medications might be causing symptoms of psychosis. This tool helps identify potential medication-induced psychosis risk based on your current medications and risk factors.

When someone suddenly starts seeing things that aren’t there, believing people are out to get them, or talking in ways that make no sense, it’s easy to assume it’s schizophrenia or another mental illness. But what if the cause isn’t their brain chemistry - it’s a pill they took yesterday? Medication-induced psychosis is more common than most people realize, and it can happen with drugs you’d never expect - from steroids and antibiotics to painkillers and even antihistamines. The good news? If caught early, it often goes away completely. The bad news? Many doctors miss it, and patients end up stuck on powerful antipsychotics they don’t need.

What Exactly Is Medication-Induced Psychosis?

Medication-induced psychosis isn’t a mental illness. It’s a reaction. It happens when a drug - prescription, over-the-counter, or even illegal - directly affects the brain in a way that triggers hallucinations, delusions, or both. The DSM-5, the official guide doctors use to diagnose mental conditions, says this kind of psychosis must appear during or within a month after taking the drug or withdrawing from it. Unlike schizophrenia, which lasts for months or years, this is usually temporary. Symptoms vanish once the drug leaves the system.

Think of it like a drug overdose - but instead of your heart stopping, your brain misfires. You don’t need to be addicted. You don’t need to be using street drugs. Even someone taking a standard dose of a common medication can slip into psychosis. Studies show up to 10% of people using cannabis develop psychotic symptoms. For cocaine users, the numbers jump: 90% report paranoid thoughts, and 96% experience hallucinations. Even steroids, which millions take for inflammation, trigger psychosis in about 5.7% of users on high doses.

Common Medications That Can Cause Psychosis

You might be surprised by what’s on this list. It’s not just illegal drugs. Many everyday medications carry this risk:

- Corticosteroids (like prednisone): Used for asthma, arthritis, autoimmune diseases. Psychosis risk: ~5.7% on high doses.

- Mefloquine: An antimalarial drug. The European Medicines Agency has logged over 1,200 psychosis cases since 1985. Travelers to malaria zones should be warned.

- Efavirenz: An HIV medication. About 2.3% of users develop severe psychiatric side effects, including psychosis. The FDA has issued safety alerts.

- Antidepressants (SSRIs, SNRIs): Rare, but documented. Especially in people with no prior mental illness.

- Antiepileptics (like vigabatrin): Can cause hallucinations and paranoia.

- Baclofen and cyclobenzaprine: Muscle relaxants. Often overlooked as a cause.

- Diphenhydramine (Benadryl): First-generation antihistamines. High doses, especially in older adults, can trigger confusion and hallucinations.

- Opioids and NSAIDs: Even ibuprofen in very high doses has been linked to psychotic episodes.

- Levodopa: Used for Parkinson’s. Can cause hallucinations in up to 40% of long-term users.

- Methylphenidate and amphetamines: ADHD meds. Overuse or misuse leads to stimulant psychosis - paranoia, auditory hallucinations.

And here’s the twist: if you take LSD or magic mushrooms, you’re not diagnosed with medication-induced psychosis - even if you’re terrified and convinced you’re dying. Why? Because the drug was meant to alter perception. You only get this diagnosis if the symptoms stick around after the high is gone.

Typical Symptoms - What to Watch For

The signs aren’t always dramatic. Sometimes they start small:

- Paranoia: Believing coworkers are spying, neighbors are poisoning food, or strangers are talking about you.

- Auditory hallucinations: Hearing voices that aren’t there - often critical, threatening, or whispering.

- Visual hallucinations: Seeing shadows move, people who vanish, or objects that shouldn’t be there.

- Incoherent speech: Jumping between topics, repeating phrases, or using made-up words.

- Memory gaps: Forgetting conversations, appointments, or even how they got somewhere.

- Emotional swings: Sudden anger, crying, or flatness - especially before full psychosis sets in.

- Disorganized behavior: Wearing layers in summer, screaming at empty rooms, or wandering off.

According to research, persecutory delusions and hearing voices are the two most common symptoms across all drug types. The timing matters too. Cocaine psychosis can hit within minutes. Alcohol withdrawal psychosis may take days. Steroid-induced psychosis often builds over a week or two. If someone starts acting strange right after starting a new med - even if it’s been prescribed - that’s a red flag.

Who’s at Highest Risk?

Not everyone who takes these drugs gets psychosis. But some people are far more vulnerable:

- People with a history of mental illness: Especially schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depression. Their brains are already more sensitive.

- Women: Studies show higher rates of medication-induced psychosis in women, possibly due to hormonal differences.

- Older adults: Slower metabolism means drugs stick around longer. Plus, they often take multiple meds - increasing interaction risks.

- Those with substance use disorders: Over 60% of people admitted for first-episode psychosis have a history of drug or alcohol abuse.

- People on multiple medications: Drug interactions are a silent killer. A statin plus a steroid plus an antihistamine? That combo can tip the balance.

Here’s the scary part: a 2019 study found only 38% of primary care doctors felt confident spotting medication-induced psychosis. Most assume it’s schizophrenia. They prescribe antipsychotics. The patient gets worse. Or worse - they don’t get better because the real cause is still in their system.

Emergency Management - What to Do Right Now

If someone is actively hallucinating, terrified, or aggressive, don’t wait. Don’t try to reason with them. Don’t argue. Call emergency services. But while you wait, here’s what helps:

- Stop the drug: If you know what caused it - like a new steroid or Benadryl - stop it immediately. But don’t quit something like an antiseizure med without medical help.

- Keep them safe: Remove sharp objects, lock away weapons, turn off the TV if it’s triggering hallucinations. Stay calm. Don’t crowd them.

- Call for help: Emergency rooms are equipped to handle this. They’ll check vitals, run blood tests, and rule out infections, low blood sugar, or seizures.

- Don’t sedate them yourself: No alcohol, no sleeping pills. That can make it worse.

In the ER, treatment is simple: stop the drug and support the body. IV fluids, electrolytes, and monitoring for complications like rhabdomyolysis (muscle breakdown from stimulants) are common. If the person is in extreme distress, doctors may give a single dose of an atypical antipsychotic - like olanzapine or quetiapine - to calm them down. But here’s the catch: there’s not strong evidence these drugs are needed for medication-induced psychosis. They’re used to buy time, not cure it.

For alcohol or benzo withdrawal psychosis, the treatment is different: a slow, controlled taper with benzodiazepines to prevent delirium tremens - a life-threatening state.

Recovery - How Long Does It Take?

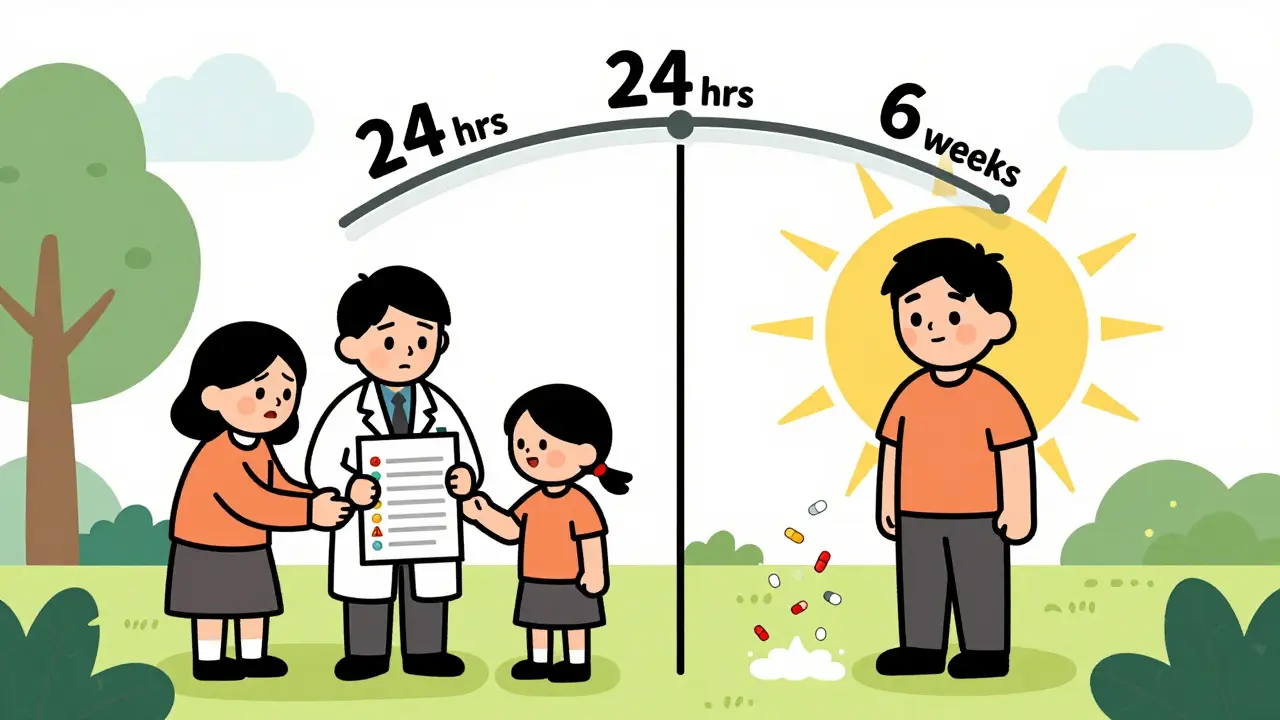

Most people recover fully. But timing varies:

- Cocaine or methamphetamine: Symptoms usually clear in 24-72 hours after last use.

- Steroids: Takes 4-6 weeks to fully resolve after stopping.

- Antidepressants: May take 1-4 weeks as the drug clears.

- Alcohol: Withdrawal psychosis can last up to a week. If it doesn’t, Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome (brain damage from thiamine deficiency) may be involved.

The key is patience. Don’t rush to label someone as schizophrenic just because they had a bad reaction. If symptoms fade within a month of stopping the drug, it’s almost certainly medication-induced. But here’s the catch: some people who had a single episode go on to develop schizophrenia later. That’s why follow-up is critical.

Prevention and What Doctors Should Do

Prevention starts with awareness. Before prescribing any high-risk drug - especially steroids, antimalarials, or antiretrovirals - doctors should:

- Ask about personal or family history of psychosis.

- Screen for current substance use.

- Warn patients: “If you start hearing voices or feel paranoid, call me immediately.”

- Monitor mood changes in the first few weeks - irritability, anxiety, or sleep loss can be early signs.

Patients, too, need to speak up. If you’ve just started a new med and feel “off,” don’t brush it off as stress. Don’t assume it’s normal. Call your doctor. Bring a list of everything you’re taking - including supplements, OTC painkillers, and herbal products.

Emerging research is looking at genetic markers that might predict who’s at risk. In the future, we might test someone’s DNA before giving them a drug like efavirenz. But for now, vigilance is the best tool.

When It’s Not Medication-Induced Psychosis

Not every psychotic episode is caused by drugs. Delirium (from infection or organ failure), brain tumors, epilepsy, and primary psychotic disorders like schizophrenia all look similar. That’s why doctors need to rule out everything else. Blood tests, brain scans, and detailed drug histories are essential. If psychosis lasts longer than a month after stopping the drug - it’s likely not medication-induced. It’s something else.

And here’s the biggest mistake: prescribing long-term antipsychotics to someone whose psychosis was drug-triggered. That’s like treating a broken leg with a cast that never comes off. The drug caused it. Remove the drug. Let the brain heal. Don’t add more chemicals.

Can over-the-counter drugs cause psychosis?

Yes. First-generation antihistamines like diphenhydramine (Benadryl) can cause hallucinations and confusion, especially in older adults or when taken in high doses. Cold medicines, sleep aids, and motion sickness pills often contain these ingredients. Even a few extra pills can push someone into psychosis.

Is medication-induced psychosis the same as schizophrenia?

No. Schizophrenia is a chronic brain disorder with no clear trigger. Medication-induced psychosis is a temporary reaction to a drug. Symptoms usually fade within days to weeks after stopping the drug. If they last longer than a month, doctors must consider whether a true psychotic disorder has emerged.

What should I do if I think a loved one has drug-induced psychosis?

Call emergency services if they’re a danger to themselves or others. If they’re calm, stop the suspected drug immediately (if safe to do so), keep them in a quiet, safe space, and contact their doctor right away. Bring a full list of all medications and supplements they’re taking. Don’t try to handle it alone.

Can you get psychosis from withdrawing from a drug?

Yes. Withdrawal from alcohol, benzodiazepines, or even some antidepressants can trigger hallucinations and paranoia. Alcohol withdrawal psychosis can occur 12-48 hours after the last drink. This is different from delirium tremens but still requires medical supervision.

Do antipsychotic drugs cure medication-induced psychosis?

Not usually. Stopping the causative drug is the cure. Antipsychotics may be used short-term in emergencies to calm severe agitation, but they don’t fix the root cause. Long-term use can mask the real issue and lead to unnecessary side effects like weight gain, tremors, or metabolic problems.

Final Thoughts

Medication-induced psychosis is not rare. It’s underdiagnosed. It’s treatable. And it’s often reversible. The biggest danger isn’t the drug itself - it’s the assumption that psychosis means a lifelong mental illness. A simple blood test, a careful drug history, and a willingness to stop the suspected medication can save someone from years of misdiagnosis and unnecessary treatment. If you or someone you know has suddenly changed behavior after starting a new drug - act fast. Don’t wait. Don’t assume. Ask: What did they start taking? That one question might be the difference between a full recovery and a lifelong mislabel.

Hariom Sharma

This is such a needed post! I work in a clinic in Delhi and see this all the time - grandpa takes Benadryl for sleep, wakes up talking to his dead wife, and they put him on antipsychotics. No one thinks to ask what he started taking last month. So many lives could be saved just by asking, "What’s new?" instead of assuming it's schizophrenia. We need more awareness, especially in places where meds are sold over the counter like candy.

Nina Catherine

OMG YES I’M SO GLAD THIS EXISTS!! My cousin went through this last year after starting prednisone for asthma. She thought she was being watched by the neighbors and started yelling at the TV. We thought it was a breakdown... turns out it was the steroids. She stopped them and was back to normal in 3 weeks. Why isn’t this on every prescription label?! 😭

Taylor Mead

Honestly, this is one of those topics that gets buried under all the mental health stigma. People don’t realize how many common meds can flip a switch in the brain. I’ve seen it in ER - someone comes in screaming about bugs crawling on their skin, and turns out they doubled up on cold medicine. No need for antipsychotics. Just stop the drug. Let the brain reset. Simple. But nobody checks the med list.

Amrit N

i had a friend who took mefloquine for a trip to thailand and started seeing people with no faces. he thought he was going crazy. doc said 'depression' and gave him sertraline. took 3 months to figure out it was the antimalarial. now he’s fine. but imagine if he’d been stuck on antipsychotics for a year. scary stuff. we gotta talk about this more.

Chris Beeley

Ah, the classic Western medical paradigm - slap a label on it, throw in a pill, call it a day. This is why global health is in shambles. In Nigeria, we don’t have the luxury of overprescribing antipsychotics like candy. We ask: what did they take? What’s their diet? Are they dehydrated? Are they sleeping? We look at the whole system. Not just the brain. And yet, here in the States, you get a 10-minute consult, a DSM-5 checklist, and a prescription for olanzapine. It’s not medicine - it’s industrialized ignorance. I’m not surprised. Your system treats symptoms like commodities.

Arshdeep Singh

Let me drop some truth bombs. You think psychosis is about drugs? Nah. It’s about control. The pharmaceutical industry doesn’t want you to know that a $2 pill can cause hallucinations because then you’d stop taking $200/month antipsychotics. They profit from chronicity. Schizophrenia? It’s a lucrative diagnosis. Medication-induced? It’s a liability. So they bury it. They gaslight patients. They call it 'relapse' when it’s just the drug still in their system. Wake up. This isn’t science - it’s capitalism wearing a lab coat.

Maddi Barnes

I love how this post says 'don't sedate them yourself' but then doesn't mention that 70% of people who experience this are elderly women taking 5+ meds at once. And yes, I'm talking about you, grandma, who's on prednisone, Benadryl, lisinopril, metformin, and melatonin. That combo? It's a psychiatric grenade. And nobody checks for interactions. 🤦♀️ Also, why isn't this in med school curricula? We're teaching students to diagnose schizophrenia before they learn to ask about OTC meds. Sad.

Jana Eiffel

The ethical imperative here is undeniable. The medical establishment’s failure to prioritize differential diagnosis in the context of iatrogenic psychosis represents a profound lapse in clinical diligence. One must question the epistemological foundations of psychiatric classification when a reversible, pharmacologically induced phenomenon is routinely subsumed under the rubric of chronic neurodevelopmental disorder. The implications for patient autonomy, informed consent, and therapeutic nihilism are profound. We must recalibrate our diagnostic frameworks to prioritize temporal causality over categorical convenience.

Tommy Chapman

I’m sick of this liberal nonsense. If your brain can’t handle a little steroid or Benadryl, maybe you shouldn’t be taking it. I served in the military - we didn’t cry when we got a new med. We took it and dealt with it. This whole 'medication-induced psychosis' thing is just another way to blame the system instead of personal responsibility. If you’re hallucinating, maybe you’re just weak. Stop making excuses.

Robin bremer

bro i took like 3 benadryl once because i was allergic and i saw a giant spider on my ceiling that wasn’t there 😱 it was wild. i thought i was dying. then i slept it off. now i’m scared to even look at allergy meds. also i love u for writing this. i’m not alone 🫂

Greg Scott

I’ve worked in pharmacy for 15 years. This happens more than people think. We have a checklist now: if a patient over 65 starts acting weird within 2 weeks of a new med, we call the prescriber immediately. No judgment. Just a quick 'Hey, did you start anything new?' Saves lives. Simple. But most docs never ask.

Scott Dunne

I find this entire discussion alarmingly naive. The notion that psychosis is 'reversible' upon discontinuation of a drug is a dangerous oversimplification. Neurochemical pathways are not light switches. Even transient exposure can leave lasting alterations in dopaminergic signaling. To suggest that a single episode precludes future schizophrenia is to ignore the prodromal literature. This post, while well-intentioned, risks encouraging premature discontinuation of necessary pharmacotherapy. Caution, not complacency, is required.