When you pick up a prescription, you might assume the pharmacist will give you the cheapest version of your medicine. But that’s not always true. It depends on where you live. In some states, pharmacists must swap your brand-name drug for a generic. In others, they can only do it if you say yes. These differences aren’t just paperwork-they directly affect how much you pay, whether you take your medicine as prescribed, and even your health outcomes.

What’s the difference between mandatory and permissive substitution?

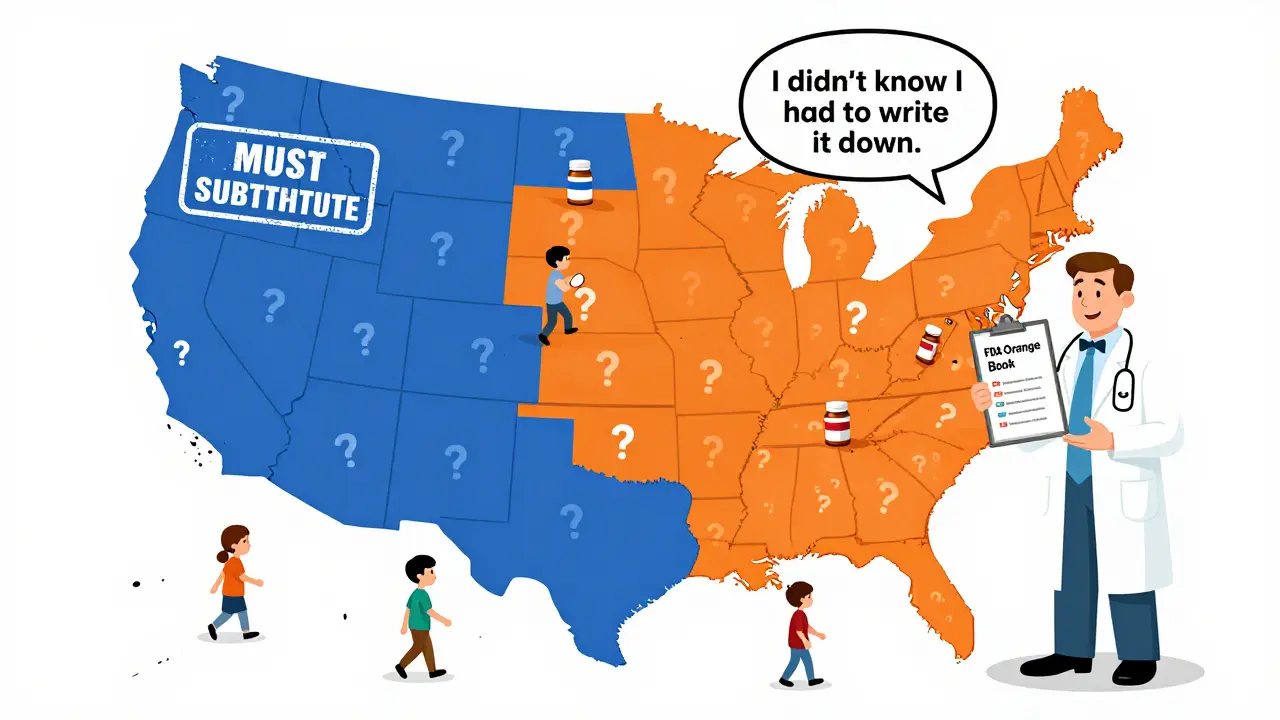

Mandatory substitution means the law forces pharmacists to switch your brand-name drug for a generic version-unless your doctor specifically says not to. Permissive substitution means the pharmacist is allowed to make the switch, but they don’t have to. They can choose to give you the brand-name drug even if a cheaper generic is available. This isn’t a federal rule. It’s decided state by state. The federal government set up the system for approving generics back in 1984 with the Hatch-Waxman Act, but it left the actual substitution rules up to each state. That’s why you can walk into a pharmacy in New York and get a generic by default, but walk into one in California and be asked if you’re okay with the switch.Which states require pharmacists to substitute generics?

As of 2020, 19 states and Washington, D.C., have mandatory substitution laws. These include Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Idaho, Indiana, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Mississippi, Montana, New Hampshire, North Dakota, and West Virginia. In these places, if a generic is available and approved as equivalent by the FDA’s Orange Book, the pharmacist must dispense it-unless the doctor writes “Dispense as Written” or “Brand Medically Necessary” on the prescription. The other 31 states use permissive substitution. Here, pharmacists can substitute generics, but they’re not required to. Some may do it routinely. Others might wait for you to ask. And in some cases, they might not substitute at all-even if it saves you money-because they’re unsure of the rules or worried about liability.It’s not just about who can substitute-it’s about how they do it

The real complexity lies in the details. Four key rules shape how substitution works in each state:- Duty to substitute: Mandatory (must) vs. Permissive (can)

- Notification: Do you have to be told when a switch happens? 31 states and D.C. require pharmacists to notify you separately-like a slip of paper or a verbal alert-not just rely on the generic label.

- Consent: Do you have to say yes? Seven states plus D.C. require your explicit permission before swapping the drug. That means even if substitution is mandatory, you can still say no.

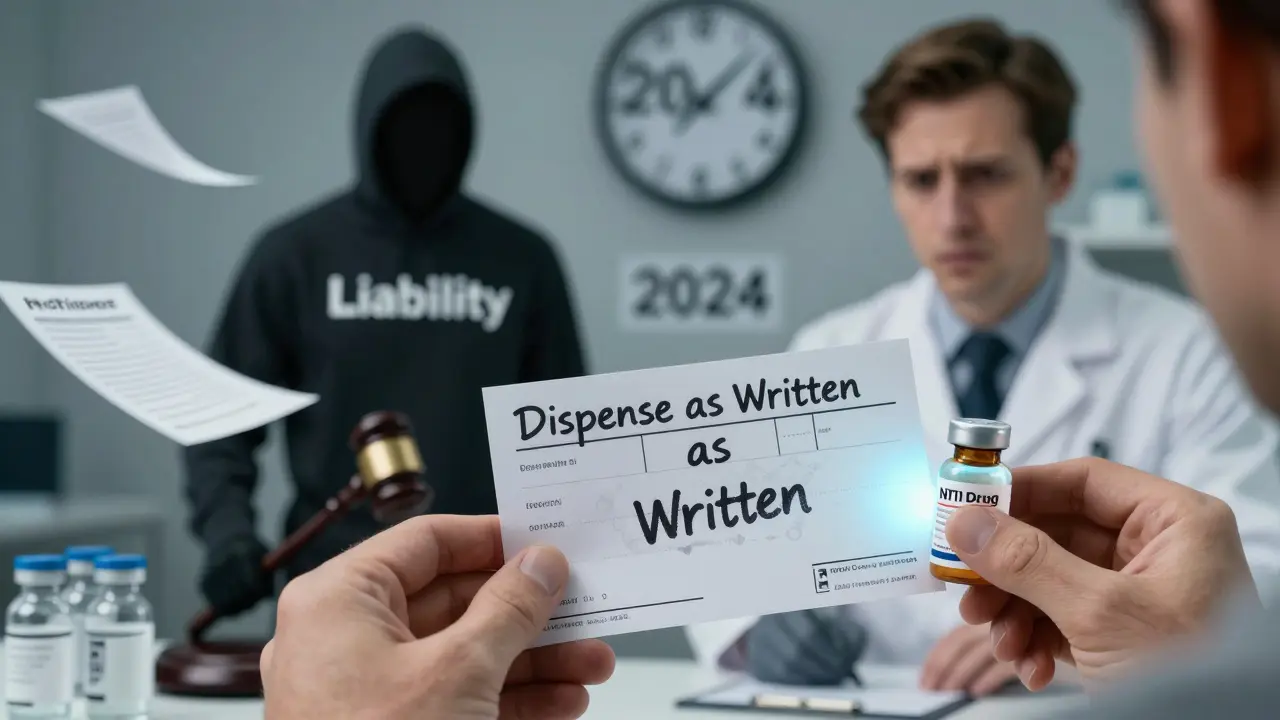

- Liability: Are pharmacists protected if something goes wrong after substitution? 24 states offer no clear legal protection. That means if you have a bad reaction after a generic is switched, the pharmacist could be sued-even if the drug is FDA-approved.

These small differences create huge gaps in real-world outcomes. A 2011 study found that six months after a brand-name drug lost its patent, states with mandatory substitution filled 48.7% of prescriptions with generics. In permissive states? Only 30%. That’s nearly a 20-percentage-point gap.

And when patient consent was required? Generic use dropped to just 32.1%. Without consent? It jumped to 98.1%. That means if you have to sign a form or give verbal approval every time, most people just don’t bother-and stick with the more expensive brand.

Why does this matter for your health and wallet?

Generic drugs cost 80 to 85% less than brand-name versions. That’s not a small savings. For someone on a chronic medication like statins, blood pressure pills, or diabetes drugs, that can mean hundreds-or even thousands-of dollars a year. Medicaid programs in mandatory substitution states saved millions because more people filled their prescriptions with generics. Higher generic use also means better adherence. People are more likely to keep taking their medicine if it’s affordable. One study showed that in states with mandatory substitution and no consent requirement, patients were significantly more likely to stay on their medication long-term. But here’s the catch: some drugs are risky to switch. Narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drugs-like warfarin, levothyroxine, or seizure medications-have very tight safety margins. A tiny change in dose or formulation can cause serious side effects. That’s why many states have extra rules for these drugs. Pharmacists in states with consent requirements are nearly twice as likely to avoid substituting NTI drugs-even when they’re allowed to-because they’re scared of legal trouble.Biosimilars are changing the game

The rules get even more complicated with biologic drugs. These are complex, injectable medications used for conditions like rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s disease, and cancer. Their cheaper versions are called biosimilars. Forty-five states treat biosimilars differently than regular generics. Most require doctors to be notified before a substitution happens. Some require patient consent. A few even demand extra recordkeeping. Only nine states and D.C. treat biosimilars the same way they treat simple generics. Why? Because biologics are made from living cells, not chemicals. Experts worry that switching between similar-but not identical-products could trigger immune reactions. While studies show biosimilars are safe, regulators are being cautious. That caution slows down adoption and keeps prices high.

How do doctors control substitution?

Prescribers have the final say. If a doctor doesn’t want a generic substituted, they can write “Dispense as Written,” “Do Not Substitute,” or “Brand Medically Necessary” on the prescription. In some states, prescriptions are printed on two-line forms-one line for the drug name, another for the pharmacist to sign if substitution is allowed. But here’s the problem: many doctors don’t know the rules in their own state. A survey found that nearly half of physicians in permissive states didn’t realize they needed to write anything special to block substitution. That means patients sometimes get generics they didn’t expect-or don’t get them when they should.What should you do?

If you’re on a long-term medication, ask your pharmacist: “Is this a generic? Is substitution mandatory here?” Don’t assume. Check your receipt. If the name changed and you weren’t told, ask why. If you’re on a narrow therapeutic index drug-like thyroid medicine or blood thinners-be extra careful. Ask your doctor if switching is safe for you. If you’re concerned, ask them to write “Dispense as Written” on your prescription. And if you’re in a state that requires consent, know your rights. You can say no to a substitution-even if the pharmacist says it’s cheaper. You’re not obligated to accept it.What’s changing?

The number of states with mandatory substitution has grown since 2014-from 14 to 19. That trend suggests more states are trying to cut costs and improve access. But as biologics and complex drugs become more common, lawmakers are adding more layers of rules instead of simplifying them. The big question is whether states will eventually standardize these laws. Right now, if you move from Texas to Vermont, your prescription might suddenly be swapped without your input. That’s confusing. It’s also inefficient for pharmacies that serve patients from multiple states. For now, the system stays messy. But understanding your state’s rules gives you power-over your health, your money, and your choices.Can a pharmacist substitute my brand-name drug without telling me?

In 31 states and Washington, D.C., pharmacists must notify you separately-like with a printed notice or verbal warning-before switching your medication. In the other 19 states, they only need to label the bottle with the generic name. If you weren’t told, you can ask why. You have the right to know what you’re taking.

Do I have to agree before a generic is given to me?

Only in seven states and Washington, D.C. In those places, pharmacists need your explicit consent before substituting-even if the law says they must substitute. In all other states, consent isn’t required. That means you might get a generic without being asked. If you don’t want it, you can refuse.

Are generic drugs as safe as brand-name drugs?

Yes. The FDA requires generics to have the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration as the brand-name drug. They must also meet the same quality standards. For most medications, generics work just as well. The exception is narrow therapeutic index drugs, where even small differences in absorption can matter. Always talk to your doctor if you’re unsure.

What if I have a bad reaction after switching to a generic?

In 24 states, pharmacists have no legal protection from liability if a patient has an adverse reaction after substitution. That means they could be sued, even if the generic is FDA-approved. Because of this, some pharmacists avoid substitution altogether, especially for high-risk drugs. If you experience side effects, report them to your doctor and pharmacist immediately.

Can I ask my doctor to block generic substitution?

Yes. Your doctor can write “Dispense as Written,” “Do Not Substitute,” or “Brand Medically Necessary” on your prescription. This legally prevents the pharmacist from switching your medication. If you’ve had a bad experience with a generic before, or if you’re on a sensitive medication, it’s perfectly reasonable to ask for this note.

Janette Martens

so like... if i move from texas to vermont and my blood pressure med gets swapped without me knowing? that's just wild. my grandma died because they switched her thyroid med and no one told her. this isn't 'savings' this is russian roulette with your life. why do we let states play god with prescriptions??

Marie-Pierre Gonzalez

Thank you for this meticulously researched and deeply important overview. The disparities in state-level pharmaceutical policy are not merely administrative-they are ethical fissures in our healthcare infrastructure. I urge all readers to contact their state legislators and advocate for standardized, transparent substitution protocols with mandatory patient notification and liability protections for pharmacists. Health equity cannot be a geographic lottery.

Louis Paré

Wow. So the real issue isn't generics. It's that pharmacists are too scared to do their job because of liability. And doctors? Too lazy to know the rules. And patients? Too dumb to ask. This isn't healthcare. It's a bureaucratic comedy of errors where the punchline is your kidney failing because you didn't read the fine print on a bottle labeled 'generic'.

Mimi Bos

my pharmacist in california just swapped my omeprazole for generic and didn't say a word. i only noticed because the pill looked different. i asked and she was like 'oh yeah, we do that here'. no form, no warning. just... done. kinda wild how random this is.

Payton Daily

LET ME TELL YOU SOMETHING. THIS ISN'T ABOUT DRUGS. THIS IS ABOUT THE SYSTEM. THE GOVERNMENT LETS BIG PHARMA OWN THE BRANDS AND THEN LETS STATES DECIDE IF YOU GET THE CHEAP VERSION. BUT IF YOU GET THE CHEAP VERSION AND YOU HAVE A REACTION? THE PHARMACIST GETS SUED. SO THEY DON'T SWAP. SO YOU PAY MORE. SO BIG PHARMA MAKES MORE. IT'S A SCAM. IT'S ALWAYS BEEN A SCAM. YOU THINK YOU'RE SAVING MONEY? YOU'RE PAYING FOR THE SCAM IN YOUR HEALTH. AND NO ONE'S HOLDING ANYONE ACCOUNTABLE.

Kelsey Youmans

Thank you for highlighting the critical nuances surrounding substitution policies. The data on adherence rates and cost savings is compelling. However, we must also consider the psychological impact on patients who experience unexpected changes in medication appearance or dosing. Standardizing notification protocols across states may improve trust and continuity of care. A unified federal framework, while complex, may ultimately serve public health more effectively than our current patchwork system.

Sydney Lee

Let’s be honest: if you’re on a narrow therapeutic index drug and you’re not getting the exact same formulation every time, you’re playing with fire. And let’s not pretend that generics are identical-bioequivalence is a statistical mirage. The FDA approves them based on population averages, not individual physiology. Your 'generic' might be fine for 95% of people. But what about the 5% who get sick? Who pays for that? The pharmacist? The patient? The system? Nobody. And that’s the real tragedy.

oluwarotimi w alaka

you think this is about drugs? nah. this is about the new world order. big pharma and the feds are pushing generics so they can track you. every time you take a pill, they log it. they want you dependent on their chemicals and their systems. and now they're forcing states to swap meds so you don't even know what you're taking. next thing you know, your blood test shows 'unauthorized substance' and they take your kids. this is control. it's always been control.

Debra Cagwin

If you're on a long-term med, please, please ask your pharmacist: 'Is this generic?' and 'Do I need to sign anything?' You have a right to know. And if you're scared to switch because of past reactions? Tell your doctor. Write 'Dispense as Written.' It's not being difficult-it's being your own advocate. You're not a number. You're not a cost center. You're human. And your health matters. 💪❤️

Hakim Bachiri

So... let me get this straight. In 19 states, they force you to take a generic-even if you're scared. In 31, they ask you nicely. And in 24 states, if you die from the switch, the pharmacist gets sued. So naturally, they do NOTHING. That’s not policy. That’s a fucking paradox. And we call this 'healthcare'? We’re not fixing systems-we’re just making them more confusing. And the only winners? Lawyers. And Big Pharma. Again.

Celia McTighe

My mom’s on warfarin and her pharmacist in Ohio always calls her before switching. She says it makes her feel safe. 🤍 I think we need to make that the standard everywhere-not because generics aren’t good, but because trust matters more than savings sometimes. And if a pharmacist takes 30 seconds to say 'hey, this changed'-that’s not a cost, that’s care. 💬❤️

Ryan Touhill

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: most people don’t care enough to ask. They take the pill, they don’t read the label, they don’t check the receipt. And then they blame the system when something goes wrong. The real failure isn’t the law-it’s the apathy. If you’re not actively managing your own prescriptions, you’re surrendering your agency. And no amount of state regulation will fix that.

Ellen-Cathryn Nash

They say generics are 'just as good.' But have you ever read the fine print on the FDA’s bioequivalence studies? The margins are absurdly wide. One pill can be 80% to 125% of the brand’s concentration. That’s not a difference-it’s a canyon. And for someone on levothyroxine? That canyon can turn a stable person into a panic attack waiting to happen. I’ve seen it. It’s not paranoia. It’s pharmacology.

Vu L

Wait, so you're telling me in some states they can swap my meds without telling me, but in others they need my signature? So if I'm in a permissive state and I don't say no, I'm basically agreeing? That's not consent-that's a trap. I'm not signing anything, I'm just walking away. This system is designed to trick people into paying more. I hate it.