Warfarin-Antibiotic Interaction Checker

Check Antibiotic Safety

Select your antibiotic to see risk level and required monitoring steps

Critical Monitoring Reminder

Check your INR 3-5 days after starting antibiotics. Do not wait for your next scheduled test.

Why Warfarin and Antibiotics Don’t Always Mix

Warfarin is one of the oldest blood thinners still in wide use today. It’s prescribed to prevent strokes, clots, and dangerous blockages in people with heart conditions like atrial fibrillation or mechanical heart valves. But if you’re taking warfarin and get an infection - say, a sinus infection, urinary tract infection, or even a dental procedure that requires antibiotics - things can get risky fast.

The problem isn’t that antibiotics are bad. It’s that they can dramatically change how warfarin works in your body. In some cases, even a short course of antibiotics can send your INR (a measure of how long your blood takes to clot) soaring. And a high INR means you’re at risk of serious bleeding - inside your brain, stomach, or elsewhere. On the flip side, some antibiotics can make warfarin less effective, raising your risk of clots. Both outcomes are dangerous.

How Antibiotics Interfere with Warfarin

There are three main ways antibiotics mess with warfarin, and knowing which one is at play helps you and your doctor respond correctly.

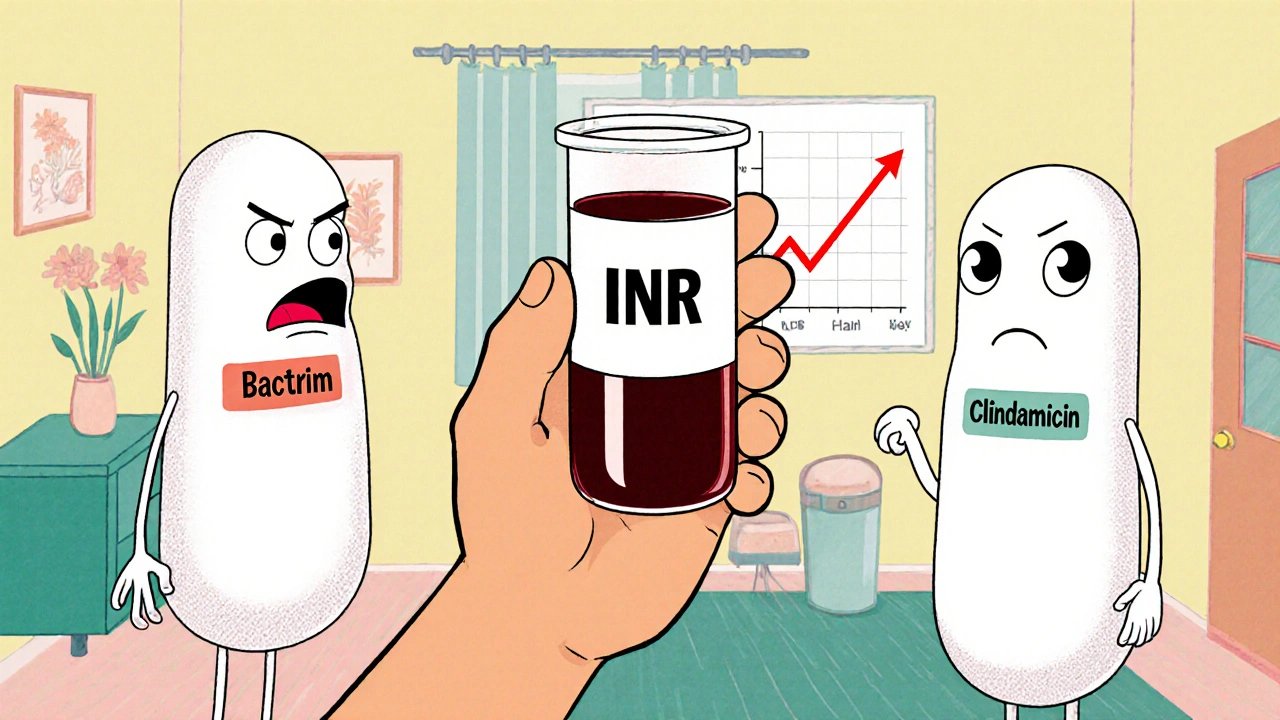

- CYP2C9 enzyme inhibition: Warfarin is broken down in your liver by an enzyme called CYP2C9. Some antibiotics block this enzyme, so warfarin builds up in your blood. This includes drugs like ciprofloxacin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim), erythromycin, and even common penicillins like amoxicillin. The effect can show up within 24 to 48 hours.

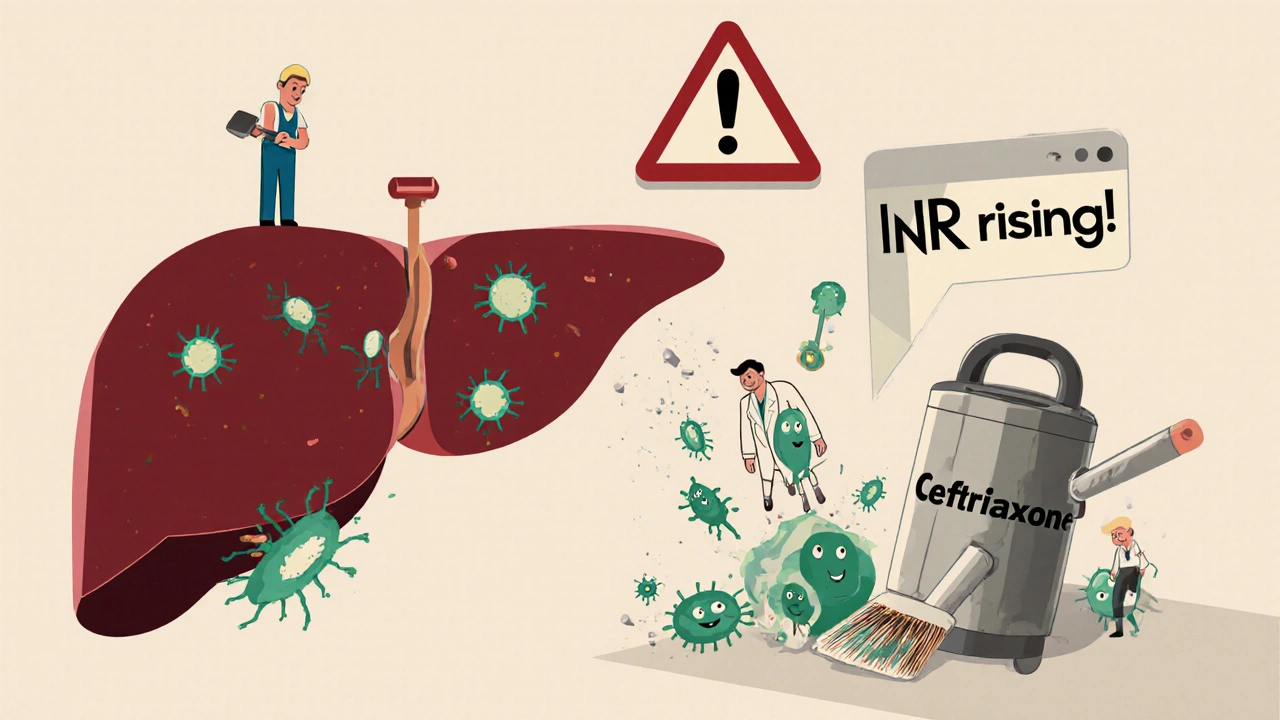

- Gut bacteria disruption: Your intestines make a small but important amount of vitamin K - the very thing warfarin tries to block. Broad-spectrum antibiotics like ceftriaxone kill off these helpful bacteria. Less vitamin K means warfarin works too well. This effect usually kicks in 3 to 5 days after starting the antibiotic.

- Protein binding displacement: Some antibiotics, especially Bactrim, cling tightly to the same protein in your blood that warfarin uses. When they show up, they kick warfarin off that protein, making more of it free and active in your bloodstream. This causes a quick, sharp rise in INR.

There’s one big exception: rifampin. Instead of blocking warfarin, it speeds up its breakdown. This can make warfarin stop working - and that’s just as dangerous. If you’re on rifampin for tuberculosis or another infection, your warfarin dose might need to go up by 50% or more. But it takes weeks for your body to adjust, so close monitoring is critical.

Which Antibiotics Are Highest Risk?

Not all antibiotics are created equal when it comes to warfarin interactions. Some are red flags. Others are low-risk.

| Risk Level | Antibiotics | Typical INR Increase | What to Expect |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Risk | Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim), Fluconazole | 1.5+ units | INR can jump sharply. Dose reduction of 25-50% often needed. Bleeding risk doubles. |

| Moderate Risk | Ciprofloxacin, Levofloxacin, Erythromycin, Amoxicillin, Ceftriaxone | 0.5-1.5 units | INR rises slowly. Monitor closely. Dose adjustment may be needed. |

| Low Risk | Clindamycin, Azithromycin, Metronidazole | Less than 0.5 units | Minimal effect. Standard INR checks are usually enough. |

For example, if you’re on warfarin and your dentist prescribes clindamycin before a tooth extraction, you’re in the clear. But if they prescribe Bactrim for a UTI, you’re entering high-risk territory. The same goes for ciprofloxacin - a common choice for travelers’ diarrhea - which can spike your INR even if you’ve been stable on warfarin for years.

What You Should Do When Starting an Antibiotic

Don’t panic. But don’t ignore it either. Here’s what works in real-world practice:

- Check your INR before you start. Get a baseline reading right before your antibiotic begins.

- Get tested again in 3-5 days. This is the most important step. Don’t wait until your next scheduled check. Most dangerous changes happen in this window.

- Watch for signs of bleeding. Unusual bruising, nosebleeds, blood in urine or stool, headaches, or dizziness could mean your INR is too high. Call your doctor immediately if you notice any of these.

- Don’t change your warfarin dose on your own. Even if your INR is high, your doctor may choose to hold your next dose instead of reducing it. Too much reduction can lead to clots later.

- Keep a log. Write down your INR numbers, antibiotic names, doses, and dates. This helps spot patterns over time.

For high-risk antibiotics like Bactrim, many clinics will reduce your warfarin dose by 25-50% before you even start the antibiotic. For moderate ones like ciprofloxacin, they might just watch closely. For low-risk ones like azithromycin, no change is usually needed.

What About Dental Work?

Many people on warfarin are told they need antibiotics before dental procedures to prevent infection. But current guidelines say that’s rarely necessary - even for people with heart valves. The risk of infection from a dental visit is extremely low, and the bleeding risk from warfarin is higher than the infection risk.

If your dentist still recommends an antibiotic, ask: Is this really needed? If yes, push for clindamycin or azithromycin. Avoid amoxicillin or ciprofloxacin unless there’s no other option.

And remember - even if you feel fine after a procedure, your INR could still be rising. Get it checked in 3 days.

What About Rifampin? The Opposite Problem

Rifampin is the odd one out. It doesn’t make warfarin stronger - it makes it weaker. It forces your liver to break down warfarin faster. Your INR will drop, sometimes over a week or two. That means your blood starts clotting too easily.

If you’re prescribed rifampin for tuberculosis or another infection, your warfarin dose will likely need to go up - by 50% or more. But here’s the catch: it takes 6 to 8 weeks for your body to fully adjust. So your doctor needs to check your INR every 1-2 weeks during that time. Stopping rifampin later will also require another round of dose adjustments.

Why Monitoring Beats Avoidance

Some doctors used to avoid giving antibiotics to people on warfarin. But research shows that’s not the answer. A 2014 study of nearly 39,000 patients found that most people on antibiotics didn’t need to change their warfarin dose - even though their INR went up slightly. The real danger wasn’t the antibiotic. It was not checking the INR.

Patients who got their INR checked within 5 days of starting antibiotics had far fewer bleeding events than those who didn’t. The key isn’t avoiding antibiotics. It’s knowing when and how to respond.

What to Do If You’re Already on Both

If you’re currently taking warfarin and an antibiotic - and you haven’t checked your INR yet - don’t wait. Call your doctor or anticoagulation clinic right away. Tell them exactly which antibiotic you’re on and when you started it. Ask if you need a blood test.

Even if you feel fine, don’t assume everything’s okay. Bleeding from warfarin interactions can be silent until it’s serious. A nosebleed you can’t stop, dark stool, or a sudden headache aren’t normal. They’re warning signs.

Bottom Line: Stay Alert, Not Afraid

Warfarin and antibiotics can be safely used together - but only with smart monitoring. You don’t need to avoid antibiotics. You need to know which ones are risky, when to test your INR, and what to do if it changes.

Remember:

- High-risk antibiotics = Bactrim, fluconazole, ciprofloxacin

- Low-risk antibiotics = clindamycin, azithromycin

- Check INR 3-5 days after starting any antibiotic

- Never change your warfarin dose without talking to your doctor

- Keep a log of your INR and antibiotics

Warfarin isn’t going away. It’s still the best choice for many people. And antibiotics are essential when you’re sick. The goal isn’t to avoid one or the other. It’s to manage them together - safely, smartly, and with the right checks at the right time.

ASHISH TURAN

This is one of the clearest breakdowns I've seen on warfarin interactions. I've been on it for 8 years and just had to switch from Bactrim to clindamycin after my INR spiked last time. Seriously, if you're on warfarin, bookmark this.

Thanks for laying it out like this.

Ryan Airey

Ugh. Another 'just check your INR' post. Like that's the solution. Doctors don't even warn patients until they're bleeding out. This is systemic negligence wrapped in a pretty infographic. You think your INR check saves you? Nah. It just makes you feel better before the ER.

And don't get me started on how they still prescribe cipro for UTIs like it's 2005.

Hollis Hollywood

I just want to say how much I appreciate how detailed this is. My mom was on warfarin for her AFib, and when she got that sinus infection last winter, her doctor just shrugged and said 'it's fine.' She ended up in the hospital with a GI bleed. I wish someone had told us about the 3-5 day window. That's the critical part. Not the antibiotic itself. It's the delay in monitoring. I'm so glad someone finally wrote this out clearly. I'm printing it out for my dad's next appointment. He's on cipro right now and I'm terrified. Thank you for making me feel less alone in this.

Aidan McCord-Amasis

Bactrim = bad. Clindamycin = good. INR check in 3 days. 🚨💊

Adam Dille

This is such a helpful guide. I’ve been on warfarin since my valve replacement and honestly, I used to panic every time I got a cold. Now I just check the list and breathe. The part about rifampin was eye-opening - I had no idea it made warfarin weaker. So counterintuitive! I’m sharing this with my whole family now. Maybe they’ll stop telling me to ‘just stop the blood thinner’ when I get sick 😅

Katie Baker

OMG YES. My dentist gave me amoxicillin last month and I freaked out and called my anticoag clinic. They laughed and said 'it's fine, just check your INR in 4 days.' I did, and it was barely up. So relieved! This post is basically my new bible. Thanks for making me feel like I'm not overreacting!

John Foster

There's a deeper truth here, beyond the pharmacology. We live in a system that treats the body as a machine - one part breaks, you replace it. But warfarin doesn't just interact with antibiotics. It interacts with fear. With ignorance. With the quiet, unspoken assumption that if you're 'stable,' you're safe. But stability is a myth. It's a snapshot. A moment. And antibiotics? They don't care about your stability. They don't know your history. They don't respect your rhythm. They just... disrupt. And we, as patients, are left holding the pieces of a system that never taught us how to listen to our own bodies. We're told to check INR. But who taught us how to feel the silence before the bleed?

Edward Ward

I've been on warfarin for over a decade, and I've had three different doctors tell me conflicting things about ciprofloxacin - one said 'avoid at all costs,' another said 'it's fine if you monitor,' and the third said 'it's not a big deal.' This post finally clarified it with evidence, not opinion. The table is gold. The 3-5 day window is non-negotiable. I've started keeping a log in my phone now - date, antibiotic, INR, symptoms. It's not just data - it's my safety net. And I didn't even know rifampin did the opposite until now. I'm so glad someone took the time to compile this. Thank you.

Andrew Eppich

This article is dangerously oversimplified. The notion that 'low-risk' antibiotics are safe is misleading. Any alteration of hepatic metabolism or gut flora is inherently risky. The reliance on INR monitoring is reactive, not proactive. A truly responsible physician would avoid all potential interactions by prescribing alternatives - not rely on patients to self-monitor with potentially life-threatening consequences. This is not medicine. It is risk management disguised as patient empowerment.

Jessica Chambers

So let me get this straight... I'm supposed to trust a chart that says clindamycin is 'low risk'... but the same chart says amoxicillin is 'moderate'? 😏

And yet, amoxicillin is literally in every kid's medicine cabinet. Meanwhile, clindamycin costs $200 and gives you C. diff? 🤔

Thanks for the 'safety guide'... I'll just keep ignoring it and hope for the best.

Shyamal Spadoni

You know what they don't tell you? That the FDA and pharma companies are in bed together. They push these 'low-risk' antibiotics because they're cheap. Meanwhile, the real danger is the INR testing system - it's all controlled by big labs. They profit when you come in. They profit when you bleed. They profit when you get a new prescription. This isn't about safety. It's about money. And they're using your fear of bleeding to keep you hooked. I stopped taking warfarin last year. Switched to turmeric. My INR's been 1.8 for 14 months. Coincidence? I think not.

Ogonna Igbo

In Nigeria, we don't have INR machines in every clinic. We don't even have antibiotics on time. You think this matters here? We give Bactrim to warfarin patients because it's the only thing in stock. If they bleed, they bleed. If they clot, they clot. This post is for rich Americans who have time to check their numbers. We don't have that luxury. We just pray. And you people write long essays? Get real.

BABA SABKA

CYP2C9 inhibition? Gut flora disruption? Protein binding displacement? Bro, you're speaking in pharma code. Let me translate: some antibiotics make your blood thinner, some make it thicker. If you're on warfarin, don't take anything new without telling your doctor. And if you're in the U.S. and can't get a blood test in 48 hours, you're already in the wrong country. This post is accurate - but it's also a symptom of a broken system. We need better anticoagulants. Not better checklists.

Chris Bryan

This is exactly why we need to stop letting foreigners and liberal doctors run our healthcare. Warfarin is a 70-year-old drug. Why are we still using it? Why not just give everyone one of those new pills? Because the FDA and AMA are too lazy to update guidelines. And now we have some guy in India telling us to check INR? This is chaos. We need leadership. Not blog posts.