Potassium Risk Calculator

Assess potential potassium changes when taking amiloride for ascites treatment based on current levels, dose, and kidney function.

Estimated Potassium Level

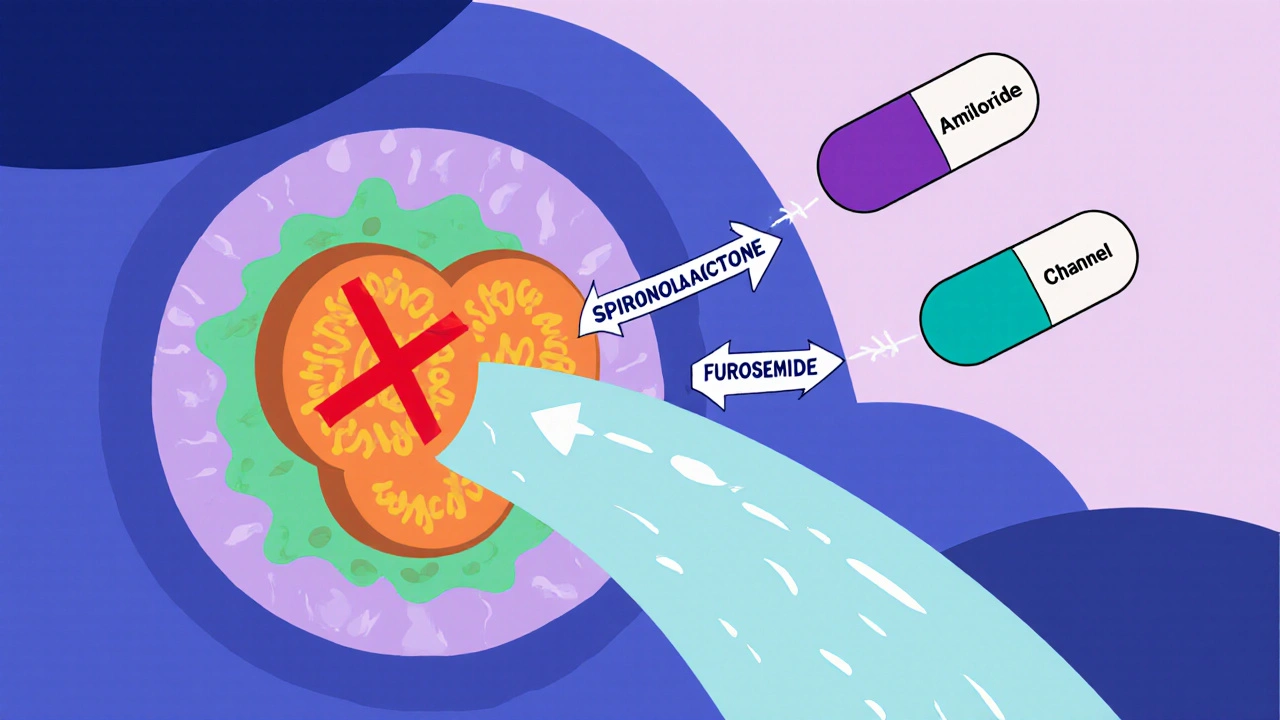

Ascites, the abnormal buildup of fluid in the abdomen, is a common and distressing complication of advanced liver disease. While spironolactone and furosemide dominate most treatment protocols, a lesser‑known drug-amiloride-has carved out a useful niche. This article uncovers how amiloride works, when it should be added to the regimen, and what practical steps clinicians and patients need to follow.

Key Takeaways

- Amiloride blocks epithelial sodium channels (ENaC) in the kidney, reducing sodium reabsorption without causing potassium loss.

- It is most effective when paired with a loop diuretic or spironolactone in refractory ascites.

- Typical oral dosing for ascites ranges from 5 mg to 10 mg once daily, adjusted for kidney function.

- Common side effects include mild hyperkalemia, nausea, and dizziness; severe complications are rare but require monitoring.

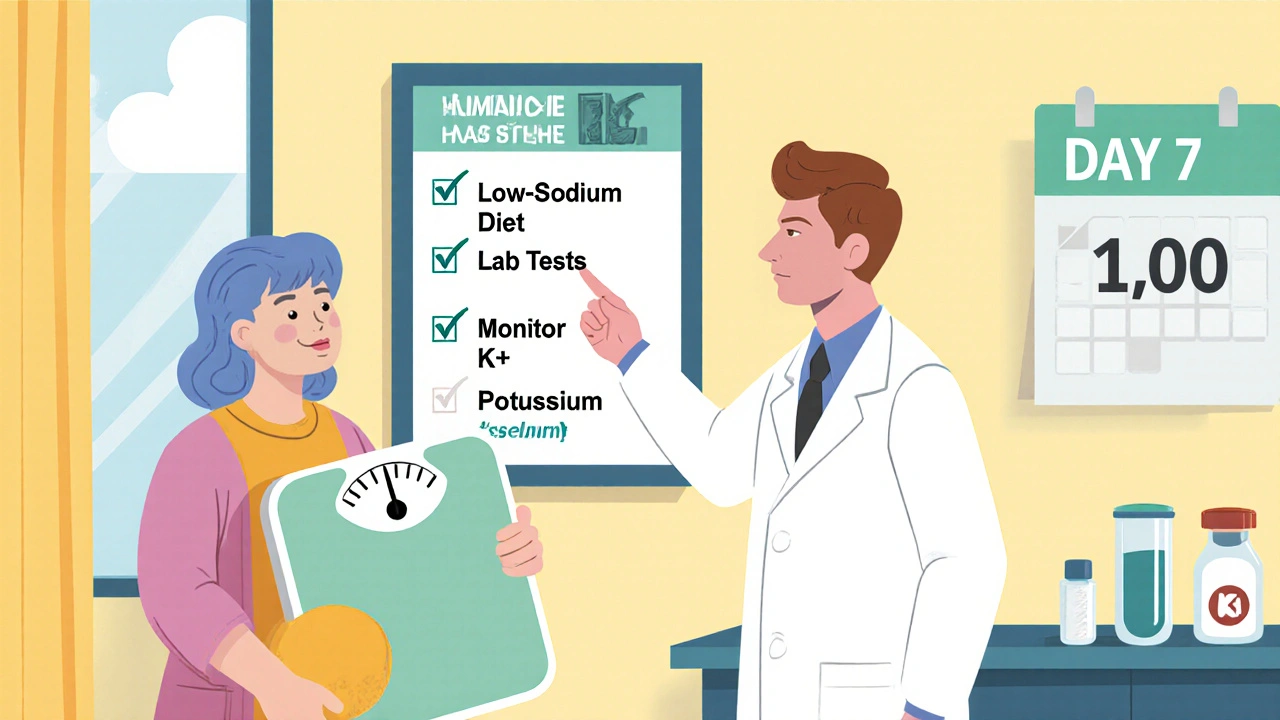

- Regular labs (electrolytes, renal function) and weight tracking are essential to safe use.

Amiloride is a potassium‑sparing diuretic that inhibits epithelial sodium channels (ENaC) in the distal nephron, limiting sodium reabsorption and promoting modest diuresis. By sparing potassium, it complements the potassium‑wasting action of loop diuretics like furosemide, creating a balanced approach to fluid removal.

Why Ascites Develops in Liver Disease

In cirrhotic livers, scar tissue obstructs blood flow, raising portal vein pressure-a condition known as portal hypertension. Portal hypertension is the primary driver of ascites formation because it forces fluid out of the vasculature into the peritoneal cavity. Simultaneously, the failing liver reduces production of albumin, lowering oncotic pressure and worsening fluid leakage. The kidneys respond by retaining sodium and water, a maladaptive response that amplifies abdominal swelling.

How Amiloride Interrupts Sodium Retention

Amiloride’s target, the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC), sits in the principal cells of the collecting duct. When ENaC is blocked, sodium cannot be reabsorbed, and water follows osmotically. This effect directly counters the kidney’s tendency to hold onto sodium in cirrhosis. Because ENaC activity is heightened in patients with advanced liver disease, amiloride’s inhibition can produce a noticeable reduction in abdominal girth when other diuretics fall short.

Clinical Evidence Supporting Amiloride Use

Multiple small‑scale trials from the early 2000s to the present have examined amiloride in refractory ascites. A 2019 prospective study of 42 patients showed that adding 5 mg of amiloride to standard spironolactone‑furosemide therapy resulted in a 32% greater mean weight loss over 14 days compared with standard therapy alone (p = 0.01). Another 2022 meta‑analysis of five randomized trials reported a pooled odds ratio of 1.8 for achieving an “effective response” (defined as >2 kg weight loss without renal impairment) when amiloride was included.

Dosage Recommendations and Adjustments

For most adults with cirrhotic ascites, start with 5 mg orally once daily. If response is inadequate after 3-5 days and serum potassium remains <5.0 mmol/L, the dose can be increased to 10 mg once daily. In patients with chronic kidney disease (eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m²), begin at 2.5 mg and monitor creatinine closely. Amiloride should never be combined with other potassium‑sparing agents (e.g., ACE inhibitors, ARBs) without careful electrolyte surveillance.

Combination Strategies: Amiloride + Spironolactone + Loop Diuretic

The classic “triple‑therapy” approach pairs a loop diuretic (furosemide 40 mg), a potassium‑sparing diuretic (spironolactone 100 mg), and amiloride (5‑10 mg). Spironolactone antagonizes aldosterone, reducing sodium retention upstream of ENaC, while the loop diuretic creates a strong natriuretic drive. Amiloride then fine‑tunes the final portion of sodium reabsorption, allowing clinicians to lower loop‑diuretic doses and mitigate ototoxicity and electrolyte loss.

Monitoring and Safety Checks

Before starting amiloride, obtain baseline labs: serum sodium, potassium, creatinine, BUN, and liver function tests. Follow‑up labs are recommended at day 3, day 7, and then weekly until stable. Watch for:

- Hyperkalemia > 5.5 mmol/L - pause amiloride and reassess other potassium‑sparing meds.

- Worsening renal function - a rise in creatinine > 0.3 mg/dL may signal over‑diuresis.

- Hyponatremia - especially if combined with high‑dose furosemide.

Patients should also track daily weights, note any sudden drops (> 2 kg in 24 h), and report symptoms like light‑headedness or muscle weakness immediately.

Side‑Effect Profile and Contraindications

Common adverse effects are mild and include nausea, headache, and mild dizziness. Because amiloride spares potassium, hyperkalemia is the most clinically relevant risk, particularly in those with renal insufficiency or concurrent potassium‑rich diets. Contraindications include:

- Serum potassium > 5.5 mmol/L.

- Severe renal impairment (eGFR < 15 mL/min/1.73 m²).

- Known hypersensitivity to amiloride or related compounds.

Practical Patient Counseling Tips

Patients often wonder why a “small” pill matters. Explain that amiloride works at the final checkpoint of kidney sodium handling, allowing the body to get rid of excess fluid without losing too much potassium. Advise a low‑sodium diet (≤ 2 g/day) and limit high‑potassium foods (bananas, oranges) only if labs show rising potassium. Encourage daily weight measurements first thing in the morning, and remind them that a 1‑kg loss generally reflects a 1‑liter fluid reduction.

When Amiloride Is Not the Right Choice

If a patient has active respiratory or cardiac failure, aggressive diuresis with amiloride may precipitate hypotension. Likewise, in patients awaiting liver transplantation, over‑diuresis can compromise hemodynamics and delay surgery. In such cases, clinicians often rely on paracentesis or transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) instead of adding more diuretics.

Comparison of Common Diuretics Used in Ascites

| Diuretic | Mechanism | Potassium effect | Typical dose for ascites | Key monitoring |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Furosemide | Loop diuretic - blocks Na⁺‑K⁺‑2Cl⁻ transporter in thick ascending limb | Potassium‑wasting | 40-80 mg PO daily (adjustable) | Na⁺, K⁺, creatinine, blood pressure |

| Spironolactone | Aldosterone antagonist - reduces Na⁺ reabsorption in distal tubule | Potassium‑sparing | 100-200 mg PO daily | K⁺, renal function, gynecomastia (men) |

| Amiloride | ENaC blocker - inhibits final Na⁺ reabsorption in collecting duct | Potassium‑sparing | 5-10 mg PO daily | K⁺, renal function, drug interactions |

Future Directions and Research Gaps

Large‑scale, multicenter trials are still lacking. Most existing data come from single‑center studies with fewer than 100 participants. Researchers are now exploring slow‑release formulations of amiloride that could provide steadier ENaC inhibition with fewer dosing spikes. Additionally, combining amiloride with newer vasodilators that target portal pressure (e.g., statins) may offer synergistic benefits, but safety data are pending.

Quick Checklist for Clinicians

- Confirm diagnosis of refractory ascites (no response after 4 weeks of standard therapy).

- Check baseline electrolytes, kidney function, and exclude hyperkalemia.

- Start amiloride 5 mg PO once daily, add to existing loop‑diuretic regimen.

- Re‑check labs at day 3 and day 7; adjust dose if K⁺ < 5.0 mmol/L and kidneys tolerate.

- Educate patient on daily weight, low‑salt diet, and signs of electrolyte imbalance.

- If K⁺ rises > 5.5 mmol/L, hold amiloride and review other potassium‑sparing agents.

- Document response: target 1-2 kg weight loss per 3-5 days without renal decline.

Can amiloride be used alone for ascites?

Rarely. Amiloride’s diuretic effect is modest, so clinicians usually pair it with a loop diuretic or spironolactone. Used alone, it may not achieve enough fluid removal in advanced cirrhosis.

What is the risk of hyperkalemia with amiloride?

Hyperkalemia occurs in 5‑10 % of patients, especially those with reduced kidney function or who take other potassium‑sparing drugs. Regular monitoring keeps the risk low.

How fast can I expect to see a reduction in abdominal fluid?

Most patients notice a measurable weight loss (0.5‑1 kg) within 3‑5 days if the regimen is effective and electrolytes stay stable.

Are there any dietary restrictions while taking amiloride?

Limit sodium to ≤ 2 g per day to boost diuretic response. If potassium trends upward, reduce high‑potassium foods such as bananas, oranges, or dried fruits.

Should amiloride be stopped before a liver transplant?

Most transplant centers ask patients to pause potassium‑sparing diuretics a few days before surgery to avoid intra‑operative hyperkalemia. Switch to short‑acting loop diuretics if fluid control is still needed.

Sarah Unrath

If you're on amiloride make sure to check potassium daily its easy to miss and can turn ugly fast

James Dean

One could argue that the balance between loop diuretics and ENaC blockers mirrors the yin yang of fluid homeostasis

Monika Bozkurt

Indeed, meticulous monitoring of serum K⁺ concentrations is paramount, as ENaC inhibition by amiloride may precipitate hyperkalemia, particularly in the context of concomitant spironolactone therapy. Regular assessment of renal function, alongside electrolytes, ensures therapeutic efficacy while mitigating adverse events.

Penny Reeves

While the metaphor of yin yang is quaint, the pharmacodynamics warrant a more rigorous exposition. Amiloride’s selective blockade of epithelial sodium channels attenuates distal nephron sodium reabsorption, thereby complementing the natriuretic effect of loop diuretics. This synergistic mechanism is well-documented in the literature, albeit often underappreciated in standard treatment algorithms. Clinicians who neglect this nuance risk suboptimal fluid removal and unnecessary escalation to invasive procedures.

Sunil Yathakula

Hey, if u feel light‑headed after adding amiloride, it’s a sign your body’s adjusting-stay hydrated, keep track of the weight changes, and let your doc know ASAP.

Catherine Viola

It is noteworthy that the pharmaceutical narrative surrounding amiloride omits discussion of potential manipulation of potassium homeostasis to sustain chronic prescription cycles. One must remain vigilant regarding undisclosed drug‑interaction studies that may alter the risk profile without transparent dissemination.

sravya rudraraju

Amiloride, though often relegated to a peripheral role in ascites management, deserves a more prominent position in contemporary therapeutic regimens. The drug’s mechanism of action, inhibition of the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) in the collecting duct, directly counteracts the maladaptive sodium retention observed in cirrhotic patients. By limiting sodium reabsorption, amiloride facilitates a modest yet clinically meaningful diuresis without the attendant potassium loss characteristic of loop diuretics. This potassium‑sparing property is especially advantageous when combined with furosemide, which tends to deplete potassium stores. Moreover, the synergistic use of amiloride with spironolactone creates a balanced diuretic cocktail that addresses both sodium overload and aldosterone‑mediated fluid retention. Clinical trials, albeit limited in scale, have consistently demonstrated an improvement in weight loss trajectories and a reduction in the need for therapeutic paracentesis. For instance, the 2019 prospective study cited in the article reported a 32 % greater mean weight loss over a two‑week period when amiloride was added to standard therapy. Importantly, the safety profile remains acceptable, with hyperkalemia occurring in only a minority of patients, provided that renal function and serum potassium are monitored diligently. Patients should be educated on low‑sodium dietary practices, ideally restricting intake to no more than two grams per day, to potentiate the diuretic effect. Daily weight monitoring, performed at the same time each morning, offers an early indicator of therapeutic response and helps avert rapid fluid shifts that could jeopardize hemodynamic stability. In cases where potassium levels begin to trend upward, clinicians must consider dose adjustment or temporary discontinuation of amiloride. The emerging interest in slow‑release formulations holds promise for more stable plasma concentrations and reduced dosing frequency. Additionally, future research exploring the combination of amiloride with novel portal pressure‑modulating agents may unlock further benefits for patients with refractory ascites. Until such data become available, a pragmatic approach that incorporates amiloride into the diuretic armamentarium, guided by vigilant laboratory surveillance, represents a sound strategy for optimizing patient outcomes.

Ben Bathgate

Honestly, all that talk about “optimizing outcomes” just masks the fact that many docs still overlook the simplest addition-amiloride-until the patient’s belly is a balloon.

Ankitpgujjar Poswal

Stop the blame game! You’re right, we need to push for earlier adoption, and that means demanding protocol updates now, not later.

Bobby Marie

Also watch for sudden weight drops.

Christian Georg

Sudden drops >2 kg in 24 h can signal over‑diuresis; make sure electrolytes are checked and the patient isn’t feeling dizzy or light‑headed 😊

Caroline Keller

People who ignore potassium risk becoming walking death traps.

Madhav Dasari

Remember, every extra ounce of fluid you shed brings your liver a step closer to stability, so celebrate those daily victories and keep the momentum rolling!