HIT 4Ts Score Calculator

The 4Ts score helps determine the likelihood of Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia (HIT) based on clinical criteria. Enter your scores for each category to calculate your probability.

Your 4Ts Score

Total Score

0

Score interpretation will appear here

When you're given heparin after surgery or for a blood clot, you expect it to protect you - not put you at risk for something worse. But in about 1 in 20 people who get unfractionated heparin for more than four days, a dangerous reaction called heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) can occur. It’s rare, but it’s serious. And here’s the twist: heparin, a blood thinner, triggers dangerous clots instead of preventing them.

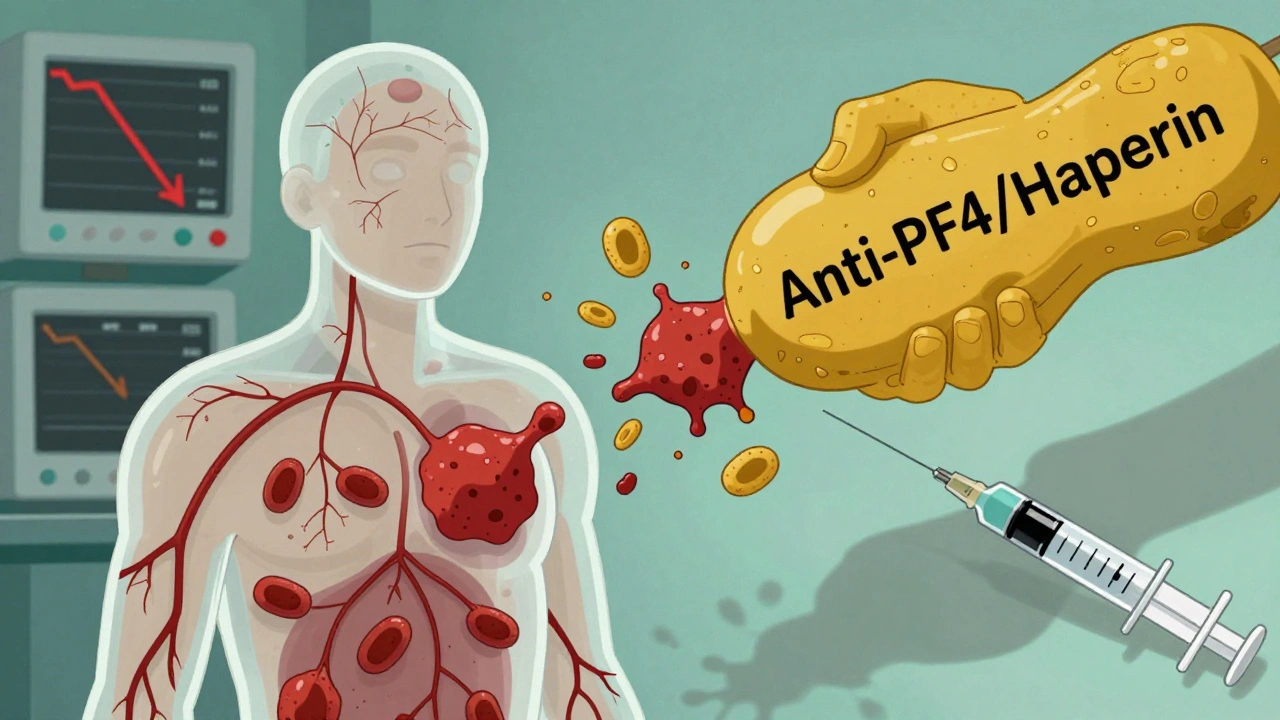

What Exactly Is HIT?

HIT isn’t just a drop in platelets. It’s an immune system mistake. Your body makes antibodies against a complex formed by heparin and a protein called platelet factor 4 (PF4). These antibodies stick to your platelets, making them activate and clump together. That’s why your platelet count plummets - and why clots form all over your body. There are two types of HIT. Type I is mild, happens within the first two days, and goes away on its own. It doesn’t need treatment. Type II is the real threat. It shows up between days 5 and 14 after starting heparin, or even faster if you’ve had heparin in the last 100 days. About half of these patients develop clots - deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, stroke, or even limb loss. This is called HITT - heparin-induced thrombocytopenia and thrombosis.Who’s at Risk?

Not everyone gets HIT. But some groups are far more likely to. Women are 1.5 to 2 times more likely than men. People over 40 face two to three times the risk of younger patients. The biggest red flag? Orthopedic surgery. After hip or knee replacements, up to 1 in 10 patients develop HIT. Cardiac surgery patients aren’t far behind. Medical patients on heparin for heart issues or DVT prevention have a lower, but still real, risk of 1 to 3%. The type of heparin matters too. Unfractionated heparin - the older, more commonly used form - carries a 3% to 5% risk. Low molecular weight heparin (like enoxaparin) is safer, but still causes HIT in 1% to 2% of cases. Even heparin flushes in IV lines or heparin-coated catheters can trigger it. About 15% to 20% of HIT cases come from these small exposures.What Are the Signs?

HIT doesn’t always scream for attention. But if you’re on heparin and notice any of these, act fast:- Sudden swelling, warmth, or pain in one leg - could be a deep vein thrombosis

- Shortness of breath or chest pain - possible pulmonary embolism

- Unexplained fever or chills

- Dark, bruised, or black patches of skin around where heparin was injected

- Blue or cold fingers, toes, or nipples - signs of small vessel clots

- Dizziness, anxiety, or rapid heartbeat

How Is It Diagnosed?

Doctors don’t guess. They use a tool called the 4Ts score. It checks four things:- Thrombocytopenia - Did your platelets drop by at least 50%?

- Timing - Did the drop happen 5 to 14 days after starting heparin? Or within 1 to 3 days if you had heparin recently?

- Thrombosis - Are there new clots?

- Other causes - Could something else explain the low platelets?

What Happens If You’re Diagnosed?

Stop heparin - all of it. That includes flushes, heparin-coated catheters, even heparin lock solutions. Continuing heparin can be deadly. You need a different blood thinner - one that doesn’t trigger the same immune reaction. The options:- Argatroban - given by IV. Used if you have liver problems. Dose adjusted based on blood tests.

- Bivalirudin - often used during heart surgery.

- Fondaparinux - a once-daily shot. Now recommended as first-line for non-life-threatening cases because it’s effective and easier to manage.

- Danaparoid - available in some countries. Not in the U.S.

How Long Do You Need Treatment?

If you had HIT without clots, you’ll need anticoagulation for 1 to 3 months. If you had HITT - clots included - you’ll need 3 to 6 months. Some people with recurrent clots need to stay on blood thinners for life.

Why Is This So Dangerous?

Untreated HIT with clots kills 20% to 30% of patients. Even with treatment, 5% to 10% lose limbs. Many survivors live with chronic pain, swelling, or organ damage. One patient case from Alberta Health Services described a woman who developed chest pain and trouble breathing just hours after noticing swelling in her calf. She was lucky - diagnosed fast. Others aren’t. The psychological toll is heavy too. Sixty-five percent of patients fear permanent disability. Eighty percent worry they’ll never be able to use heparin again - even if they need it for a future surgery or heart attack.What’s Being Done to Fix This?

Heparin is used in over a million U.S. patients every year. That means 50,000 to 100,000 cases of HIT happen annually. The cost? Up to $50,000 extra per HITT case. That’s why hospitals now monitor platelet counts every 2 to 3 days between days 4 and 14 of heparin therapy. New tests are coming. Researchers are developing PF4-only assays that skip heparin entirely - these could cut false positives from 15% to under 5%. Two new drugs in Phase II trials are designed to mimic PF4 without triggering antibodies. If they work, they could replace heparin in the future. The FDA requires black box warnings on all heparin products. The Joint Commission lists HIT prevention as a national patient safety goal. But awareness still lags. One study found 10% to 15% of patients kept on heparin even when HIT was suspected - because doctors didn’t recognize the signs.What Should You Do?

If you’re on heparin:- Know the signs - swelling, pain, skin changes, trouble breathing.

- Ask your care team if they’re checking your platelet count every few days.

- Speak up if you feel something’s wrong - even if it seems minor.

- Keep a record of when you got heparin. If you need it again in the next 100 days, tell your doctor immediately.

Kay Jolie

Okay, let’s just pause for a second and appreciate how *elegant* the immunopathology of HIT is - it’s not just a side effect, it’s a molecular betrayal. Heparin binds PF4, the immune system misreads it as a pathogen, and suddenly your platelets become rogue assassins. It’s like your body threw a rave and invited the wrong crowd. The 4Ts score? Brilliant clinical heuristics. But let’s be real - if you’re not running a PF4 ELISA within 24 hours of suspicion, you’re playing Russian roulette with a thrombotic grenade. And don’t even get me started on warfarin monotherapy. That’s not treatment - that’s a death warrant wrapped in a prescription.

Also, danaparoid being unavailable in the US? Unforgivable. We have the tech, the funding, the infrastructure - yet we still treat this like a footnote in a hematology textbook. We need better access. We need better awareness. We need to stop treating HIT like it’s a rare curiosity and start treating it like the silent killer it is.

pallavi khushwani

It’s wild how something meant to save lives can turn against you like that. I think about how much we trust medicine - injections, IVs, pills - and then realize how little we actually know about what’s happening inside. HIT feels like a whisper that becomes a scream. And the fact that even tiny amounts - like heparin flushes - can trigger it? That’s the kind of detail that keeps me up at night. Maybe we need to think less about ‘drugs’ and more about how our bodies interpret them. Not all reactions are about dosage. Sometimes it’s about meaning. And our bodies… they remember.

Also, I’m glad they’re working on PF4-only assays. That’s the kind of innovation that doesn’t just fix a problem - it changes the conversation.

Clare Fox

so like… i had a cousin who got heparin after knee surgery and she got a weird bruise and then her platelets dropped and everyone acted like it was no big deal until she almost had a stroke. then they were like ohhhhh HIT. but why did it take so long to test? why is this still not routine? i just don’t get why hospitals don’t just check platelets every 3 days like they say they should. it’s not hard. it’s not expensive. it’s just… neglected.

also the skin discoloration thing? yeah that’s a red flag. i saw pics. it looked like a burn. but no one told her to stop heparin until it was too late. so yeah. just… check the numbers. please.

Akash Takyar

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia is a critical, yet underappreciated, iatrogenic condition. The immune-mediated mechanism, involving PF4-heparin complexes, represents a paradigm of molecular mimicry gone awry. Early detection via the 4Ts scoring system, followed by confirmatory serological testing, remains the cornerstone of management. It is imperative that clinicians maintain vigilance, particularly in post-operative populations, where incidence is highest. Delayed diagnosis correlates directly with increased morbidity and mortality. Prophylactic platelet monitoring between days 4 and 14 is not optional - it is a standard of care. Furthermore, the avoidance of warfarin until platelet recovery is non-negotiable. These are not suggestions. They are evidence-based imperatives.

Andrew Frazier

Ugh. Another one of these ‘medical horror stories’ where the answer is just ‘stop using heparin.’ But we’re talking about a drug that’s been used for 90 years. It’s not like we can just swap it out for some fancy new $10,000-a-dose biologic. And don’t get me started on ‘PF4-only assays’ - yeah, sure, let’s spend half a billion dollars on new tests while our hospitals can’t even hire enough nurses. HIT is rare. Like, 1 in 2000 rare. Meanwhile, 50 million Americans get blood clots every year from sitting too long or flying. Why are we panicking over a needle prick when the real problem is that nobody moves anymore?

Also, women are more at risk? Of course they are. Their bodies are more ‘sensitive.’ That’s why they cry at movies and get migraines from the wind. It’s biology, not a conspiracy.

Just give me my heparin. I’ll take my chances.

Karen Mitchell

It is profoundly irresponsible to publish content that suggests heparin, a life-saving anticoagulant, carries a non-trivial risk of thrombosis without simultaneously emphasizing that the overwhelming majority of patients experience no adverse effects. This article reads like a fear-mongering pamphlet distributed by a fringe anti-pharmaceutical group. The fact that 99% of patients tolerate heparin without incident is buried beneath sensationalized anecdotes and dramatic language. You are not helping. You are terrifying people who need this medication. There is a difference between awareness and alarmism. This is alarmism. And it is unethical.

Furthermore, the suggestion that ‘even heparin flushes’ can cause HIT is misleading. The risk is statistically negligible in that context. To imply otherwise is irresponsible medical misinformation.

Geraldine Trainer-Cooper

so like... hit is just your body being like 'nope' to heparin? weird. i mean, why does it even make antibodies to a drug? drugs aren't alive. it's like your immune system got confused and thought a spoon was a snake. but yeah. the skin turning black? that's not a vibe. i'm just glad they have alternatives now. i wouldn't want to be the one who gets a clot because someone forgot to check a number.

Kenny Pakade

Let me guess - this is one of those ‘American healthcare is broken’ pieces written by someone who thinks a blood test costs $10,000. HIT happens. It’s rare. It’s treatable. We have protocols. We have labs. We have drugs. But no, instead of saying ‘check platelets every 3 days,’ you wanna turn this into a horror movie. And then you throw in that stat about 15-20% of cases coming from flushes? Yeah, that’s because people are dumb and don’t know how to use IV lines. It’s not a systemic failure - it’s a training failure. Fix the nurses, not the drug.

Also, why are we letting women scare everyone? They’re 1.5x more likely to get HIT? Cool. So maybe don’t give heparin to women? Just kidding - that’s not how medicine works. But you act like it’s a gender conspiracy. Grow up.

Dan Cole

Let’s be unequivocal: HIT is not a ‘side effect.’ It is an autoimmune catastrophe. The PF4-heparin complex is not a passive trigger - it is a molecular trapdoor. The immune system doesn’t ‘mistake’ it - it is *engineered* by the structure of heparin to form neoepitopes that activate FcγRIIa receptors with terrifying efficiency. The serotonin release assay isn’t just ‘gold standard’ - it’s the only test that demonstrates functional platelet activation, the actual pathophysiological mechanism. Everything else is screening.

And let’s dismantle the myth that fondaparinux is ‘first-line.’ It’s not approved for HIT in the U.S. - it’s used off-label. The real first-line is argatroban or bivalirudin. And yes - danaparoid should be available here. The FDA’s inertia is not a virtue - it’s negligence. We have 50,000 cases annually. We have the science. We have the tools. What we lack is the will.

And warfarin? Never. Not even close. The risk of skin necrosis is not a ‘possible’ side effect - it’s a near-certainty in untreated HIT. This isn’t medical nuance. It’s survival.

Billy Schimmel

man. i just read this whole thing and i’m glad i’ve never needed heparin. but also… if i ever do, i’m gonna ask for my platelet count every few days. like, i don’t care if they think i’m annoying. i’d rather be the weirdo who asked too many questions than the one who ends up with a clot and no idea why.

also… the part about skin turning black? that’s wild. i’m gonna remember that. if i ever see that, i’m out.

Kay Jolie

And yet, despite all the evidence, the Joint Commission still lists HIT prevention as a ‘goal’ - not a mandate. That’s like calling ‘fire exits’ a ‘suggestion.’ If you’re not monitoring platelets on days 4–14, you’re not just being lazy - you’re violating the standard of care. And the fact that 10–15% of patients are still kept on heparin even when HIT is suspected? That’s not ignorance. That’s institutional denial. We’ve had the tools for decades. We just don’t have the courage to use them.

Also, the new PF4-only assays? They’re not ‘coming.’ They’re already here. The FDA just hasn’t approved them because the pharmaceutical industry doesn’t profit from diagnostics. They profit from drugs. And that’s the real tragedy.