Enteric vs Foodborne Illness Identifier

This tool helps determine whether your illness is more likely an enteric infection or a foodborne illness based on symptom duration and exposure history.

Quick Take

- Enteric infections affect the intestinal tract, while foodborne illnesses are a subset caused by contaminated food.

- Both share symptoms like diarrhea and vomiting, but their sources and typical germs differ.

- Knowing the exact cause guides proper treatment and prevention steps.

- Good kitchen hygiene stops most foodborne cases; clean water and sanitation curb broader enteric outbreaks.

- Seek medical help if symptoms last more than a few days or you have a high fever.

What Is an Enteric infection is an infection that targets the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, typically the stomach and intestines?

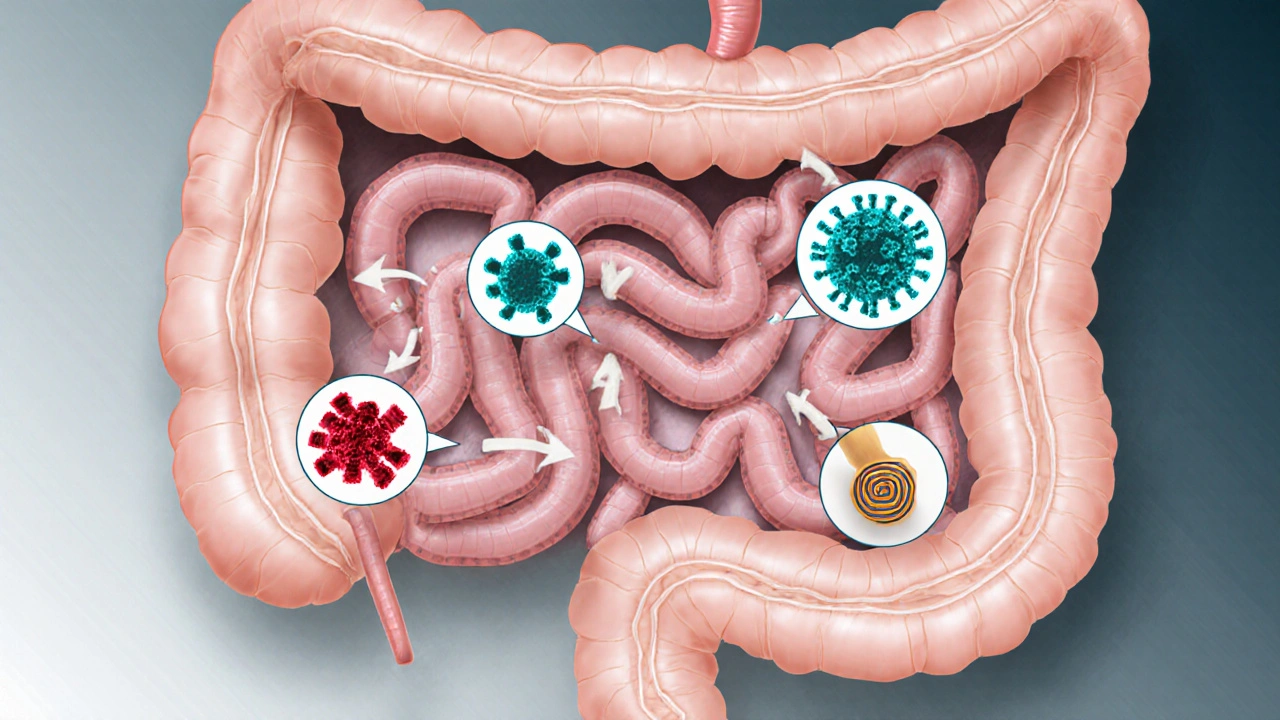

Enteric infections can be caused by bacteria, viruses, parasites, or even fungi that enter the body through contaminated water, hands, or food. The term “enteric” comes from the Greek word “enteron,” meaning intestine. These infections don’t care whether the pathogen arrives on a lettuce leaf or a public restroom faucet - if it reaches the gut, it can cause trouble.

Common routes include:

- Drinking untreated water.

- Consuming raw or under‑cooked foods.

- Hand‑to‑mouth transfer after touching contaminated surfaces.

What Is a Foodborne illness is a type of enteric infection that specifically originates from ingesting contaminated food or beverages?

When we hear “foodborne illness,” we often picture a bad batch of sushi or a tainted batch of milk. The key factor is the food source. The same pathogen that causes a broad enteric infection can also cause a foodborne case if it contaminates what we eat.

Typical ways food becomes hazardous:

- Improper cooking temperatures (e.g., under‑cooked poultry).

- Cross‑contamination during preparation (e.g., raw meat juices on vegetables).

- Storage at unsafe temperatures that let bacteria multiply.

Where Do They Overlap?

All foodborne illnesses are enteric infections, but not all enteric infections are foodborne. Think of the relationship like squares and rectangles - every square is a rectangle, yet rectangles can be much larger and come in many shapes.

Both share:

- Similar core symptoms (diarrhea, abdominal cramps, nausea).

- Potential for dehydration, especially in children and the elderly.

- Need for proper hygiene to break the transmission chain.

Where they diverge is in the primary source and often in the incubation period - the time from exposure to symptom onset.

Common Pathogens You May Hear About

Below are the most frequent culprits behind enteric and foodborne cases. Each is introduced once with microdata so search engines can recognize them as distinct entities.

Salmonella is a bacterial genus that commonly infects poultry, eggs, and raw produce. Symptoms appear 6‑72 hours after ingestion and often include fever, abdominal cramps, and watery diarrhea.

Escherichia coli (commonly shortened to E. coli) is a bacterial species where certain strains, like O157:H7, cause severe gut inflammation. It’s usually linked to under‑cooked ground beef or contaminated leafy greens.

Norovirus is a highly contagious virus that spreads through contaminated food, water, or close contact. Often dubbed the “stomach flu,” it leads to sudden vomiting and watery diarrhea.

Campylobacter is a bacterial species commonly found in raw poultry and unpasteurized milk. It causes bloody diarrhea and can lead to Guillain‑Barré syndrome in rare cases.

Listeria monocytogenes is a bacterium that thrives in refrigerated environments, often contaminating soft cheeses and deli meats. While symptoms may be mild for healthy adults, it’s dangerous for pregnant women and immunocompromised individuals.

Antibiotic therapy is the medical use of antibiotics to treat bacterial enteric infections, when indicated. Not all gut infections need antibiotics; many are viral and resolve on their own.

Hygienic practices is behaviors like proper hand washing, safe food handling, and clean water usage that prevent pathogen spread. Consistently applying these practices cuts the risk of both enteric and foodborne illnesses dramatically.

Symptoms and Diagnosis: Spot the Differences

While the symptom list overlaps heavily, a few clues hint at the source.

- Incubation time: Foodborne illnesses often have shorter incubation (hours to a day) compared to some enteric infections acquired from water, which may take a few days.

- Fever presence: Bacterial foodborne cases like Salmonella usually bring a fever, whereas viral enteric infections (e.g., norovirus) might not.

- Blood in stool: Certain bacteria (E. coli O157:H7, Campylobacter) cause bloody diarrhea, suggesting a food-related source.

Doctors confirm the cause through stool cultures, PCR panels, or toxin assays. In outbreak settings, public health labs may use whole‑genome sequencing to trace the pathogen back to a food source.

Treatment Options: When to Rest and When to Medicate

Most mild cases resolve with hydration and rest. Key steps:

- Drink plenty of oral rehydration solutions or clear fluids.

- Avoid anti‑diarrheal drugs for bacterial infections unless prescribed, as they can trap toxins.

- Seek medical care if you have high fever, blood in stools, or dehydration signs.

For bacterial culprits like Salmonella or severe E. coli infections, clinicians may prescribe antibiotic therapy after confirming susceptibility. Viral agents such as norovirus merely need supportive care.

Prevention Strategies: Break the Chain Before It Starts

Because the routes overlap, a solid hygiene routine covers both.

- Hand washing: Use soap and warm water for at least 20 seconds, especially after bathroom use and before handling food.

- Proper cooking: Heat poultry to 165°F (74°C) and ground meats to 160°F (71°C). Use a food thermometer.

- Separate raw and ready‑to‑eat foods: Keep cutting boards, plates, and utensils distinct.

- Refrigerate promptly: Store perishable items at ≤40°F (4°C) and discard anything left out >2hours.

- Safe water: Drink filtered or boiled water when traveling to regions with questionable sanitation.

- Know the high‑risk groups: Pregnant people, young children, seniors, and immunocompromised individuals should avoid raw milk, undercooked eggs, and deli meats unless heated.

Understanding a foodborne illness helps you pinpoint the steps that matter most in your kitchen.

Side‑by‑Side Comparison

| Aspect | Enteric Infection | Foodborne Illness |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Source | Water, hands, surfaces, or food | Contaminated food or drink |

| Typical Pathogens | Salmonella, E. coli, Norovirus, Giardia, etc. | Salmonella, E. coli O157:H7, Listeria, Campylobacter, Norovirus |

| Incubation Period | Hours to several days | Typically 6‑48hours |

| Core Symptoms | Diarrhea, abdominal cramps, nausea, sometimes fever | Same, with added focus on vomiting for many viral foodborne cases |

| Key Prevention | Hand hygiene, safe water, sanitation | All of the above + proper cooking, storage, cross‑contamination control |

Frequently Asked Questions

Can a foodborne illness become an outbreak?

Yes. When a contaminated batch of food reaches many people, health agencies can trace it back to the source and issue recalls. Classic examples include the 2011 Salmonella outbreak linked to contaminated eggs in the United States.

Do antibiotics work for all gut infections?

No. Antibiotics target bacteria, not viruses or parasites. Overusing them can promote resistance and may even worsen some infections, like certain strains of E. coli that release toxins when killed.

How long does it take to recover?

Mild cases often improve within 24‑48hours with hydration. Bacterial infections may take up to a week, while viral illnesses usually resolve in 3‑5 days. Persistent symptoms beyond a week merit a medical visit.

Is it safe to travel abroad with a stomach bug?

Traveling while symptomatic spreads the pathogen to others, especially on planes or in hotels. It’s best to rest, stay hydrated, and seek care before continuing your trip.

What’s the best way to disinfect kitchen surfaces?

A solution of 1tablespoon bleach per 1gallon of water, applied for at least 1minute, kills most bacteria and viruses. Commercial kitchen sanitizers work too, as long as you follow label instructions.

Holly Hayes

If your gut’s acting up, you’re probably misdiagnosing the source-enteric infections aren’t just foodie drama.

Matthew Shapiro

The distinction often hinges on exposure history; water‑borne pathogens tend to linger longer than a quick bite of contaminated food.

Also, fever is more common with bacterial enteric infections, whereas many foodborne illnesses are viral and may not cause a fever.

Julia Phillips

Imagine the drama of a night out gone wrong-your dinner plate could be the villain, but the real culprit might be the tap water you sipped earlier.

We’ve all felt that gut‑wrenching twist, and understanding whether it’s a classic foodborne blunder or an insidious enteric invader can guide proper care.

Richa Punyani

Dear reader, kindly note that while the table outlines key differences, individual cases may deviate; always consider consulting a healthcare professional for persistent symptoms.

Proper hand hygiene, safe water practices, and thorough cooking remain paramount in preventing both categories of illness.

Bhupendra Darji

Agreed, the chart is handy, but remember that overlap exists-some pathogens appear in both groups, so a holistic approach to prevention is best.

Robert Keter

When parsing the nuanced terrain of gastrointestinal distress, one must first acknowledge the sheer diversity of etiological agents that can afflict the human digestive tract, ranging from bacterial culprits such as Salmonella and Escherichia coli to viral adversaries like Norovirus and even parasitic invaders such as Giardia.

It is imperative to recognize that the incubation periods for these pathogens differ markedly; for instance, certain bacterial infections may manifest within mere hours, whereas some viral agents patiently bide their time, emerging after a full day or more.

The clinical presentation, though often overlapping with diarrhea, abdominal cramping, and nausea, can be subtly differentiated by the presence or absence of fever, which tends to be more prevalent in bacterial enteric infections.

Equally important is the route of exposure: contaminated water and surfaces frequently serve as reservoirs for enteric pathogens, while foodborne illnesses typically stem from mishandled or undercooked fare.

One cannot overlook the role of host factors; immunocompromised individuals, the elderly, and young children are disproportionately vulnerable to severe outcomes.

Management strategies must be tailored accordingly: rehydration remains foundational, yet antibiotics are judiciously reserved for confirmed bacterial etiologies, given the risk of resistance and potential harm in viral contexts.

Moreover, the public health implications differ; foodborne outbreaks often trigger swift recalls and regulatory scrutiny, whereas enteric infections may require extensive water quality monitoring and community-level interventions.

Preventive measures, therefore, should be multilayered: rigorous hand hygiene, proper food storage temperatures, thorough cooking, and the use of safe drinking water all intersect to reduce risk.

In clinical practice, a thorough patient history that captures recent travel, dietary exposures, and water sources can be the decisive factor in distinguishing between these categories.

Finally, ongoing research continues to elucidate novel pathogens and resistance patterns, underscoring the necessity for clinicians to stay abreast of emerging data to optimize patient outcomes.

Rory Martin

One must consider that the agencies overseeing food safety could be underreporting incidents, allowing contaminants to circulate unnoticed.

Furthermore, the focus on surface sanitation might distract from deeper systemic issues in water treatment infrastructure.

In any case, vigilance is essential.

Maddie Wagner

Let’s break it down together: proper handwashing, cooking foods to safe internal temperatures, and storing leftovers promptly are your best allies.

Remember, even a single lapse can turn a harmless meal into a health hazard.

Stay proactive, and you’ll keep both enteric and foodborne threats at bay.

Boston Farm to School

cool tip: keep a small bottle of bleach solution in your fridge for quick surface wipes 😊

Emily Collier

Reflecting on the information, it becomes clear that knowledge empowers us to make better choices; by understanding the subtle distinctions, we can act wisely and prevent unnecessary suffering.

Optimism thrives when we combine science with everyday habits, fostering a healthier community.