When a generic drug company wants to prove its product works just like the brand-name version, it doesn’t test it on thousands of people. It doesn’t even test it on hundreds. It uses a clever, efficient method called a crossover trial design. This isn’t just a statistical trick-it’s the backbone of how regulators like the FDA and EMA decide whether a generic drug can be sold. And if you’re wondering why generic drugs are so much cheaper but just as effective, the answer starts here.

How Crossover Trials Work in Bioequivalence

In a crossover trial, each volunteer takes both the test drug (the generic) and the reference drug (the brand-name original), but not at the same time. They take one first, wait a while, then take the other. This means every person becomes their own control. If your body absorbs the brand drug at a certain rate, you’re the perfect benchmark for how your body handles the generic. No need to compare you to someone else’s metabolism, age, or genetics-those variables cancel out.

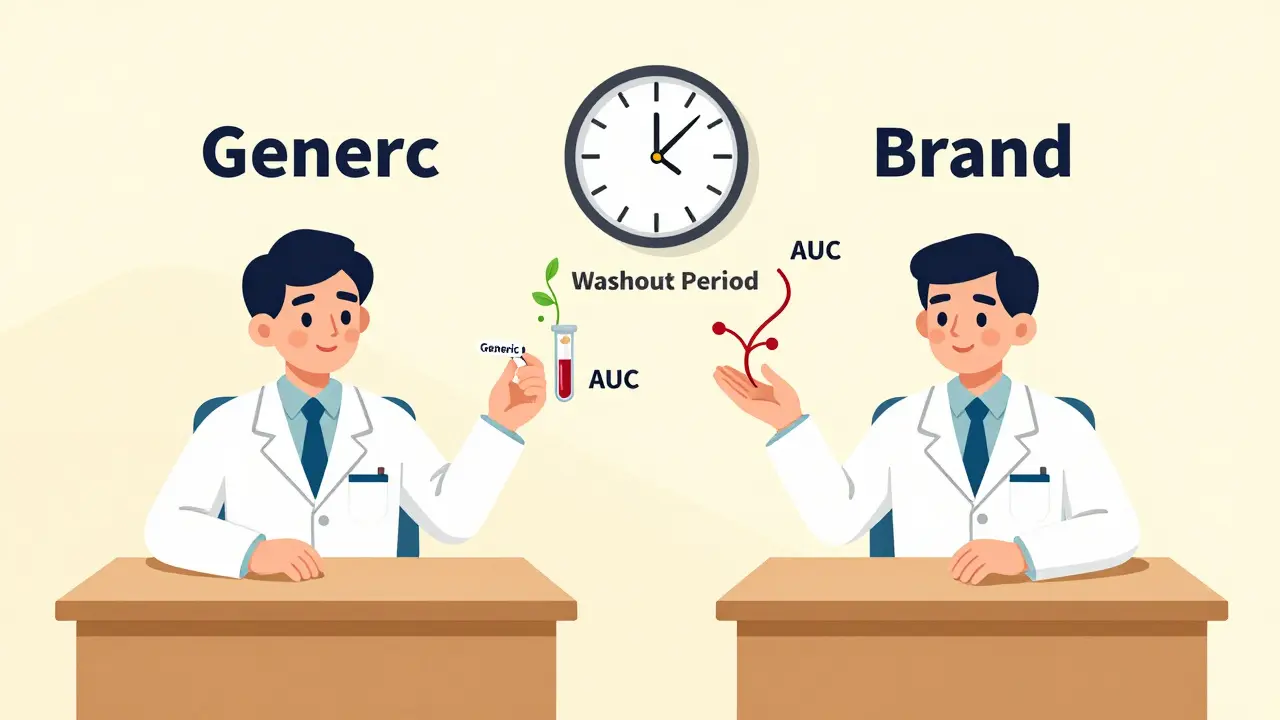

The most common setup is the 2×2 design: half the volunteers get the generic first, then the brand (AB sequence), and the other half get the brand first, then the generic (BA sequence). This balances out any timing effects. After each dose, researchers take multiple blood samples over hours or days to track how much of the drug enters the bloodstream and how long it stays there. The key measurements are AUC (total exposure) and Cmax (peak concentration). If the ratios of these values between the two drugs fall within 80% to 125%, regulators say they’re bioequivalent.

Why This Design Beats Parallel Studies

Imagine running a parallel study instead-half the people get the generic, half get the brand, and you compare the groups. Sounds simple, right? But people vary wildly in how they process drugs. One person might metabolize everything quickly; another might hold onto it for days. That noise makes it hard to tell if differences come from the drug or just the people. To get reliable results, you’d need 60, 70, even 100 participants.

In a crossover design, because each person serves as their own control, you can cut that number dramatically. For drugs with moderate variability (intra-subject CV around 20%), you might only need 24 people. That’s a six-fold reduction in sample size compared to parallel studies. That means lower costs, faster results, and less burden on volunteers. The math is solid: when between-person differences are twice as big as measurement error, crossover trials need just one-sixth the participants to achieve the same statistical power.

Washout Periods: The Silent Rule

There’s one catch: you can’t just switch from one drug to the next the next day. The first drug has to fully clear your system. That’s where the washout period comes in. Regulators require it to be at least five elimination half-lives of the drug. For a drug like warfarin, with a half-life of about 40 hours, that means waiting nearly nine days. For slower drugs, like some antidepressants or long-acting insulin, this becomes impossible. That’s why crossover designs aren’t used for every drug.

Getting this wrong is a common reason studies fail. One statistician on ResearchGate shared how his team’s study got rejected because they used a seven-day washout for a drug with a 10-day half-life. Residual drug in the blood skewed the second period’s results. They had to restart the whole study with a replicate design, costing nearly $200,000 extra. It’s not just a waiting game-it’s a precision science.

What Happens When Drugs Are Too Variable?

Some drugs are naturally unpredictable in how people absorb them. These are called highly variable drugs (HVDs), where the intra-subject coefficient of variation exceeds 30%. For these, the standard 80-125% range doesn’t work. If you tried to force it, you’d need hundreds of volunteers to get a clear signal.

That’s where replicate crossover designs come in. Instead of two periods, you use four. The most common are the partial replicate (TRR/RTR) and full replicate (TRTR/RTRT). In a partial replicate, each person gets the reference drug twice and the test drug once. In a full replicate, both drugs are given twice. This lets researchers measure how much variability comes from the drug itself-not just from the person.

With this data, regulators can use a method called reference-scaled average bioequivalence (RSABE). Instead of a fixed 80-125% range, the acceptable window widens based on how variable the reference drug is. For example, if the reference drug has a 40% CV, the limit might stretch to 75-133%. This keeps the standard fair and realistic. In 2015, only 12% of HVD approvals used RSABE. By 2022, that number jumped to 47%. It’s now the go-to for drugs like clopidogrel, levothyroxine, and many antiretrovirals.

Statistical Analysis: It’s Not Just Ratios

It’s easy to think bioequivalence is just about comparing average numbers. But it’s more nuanced. The analysis uses linear mixed-effects models-typically in SAS or R-to test three things: sequence effects (did the order matter?), period effects (did time itself affect results?), and treatment effects (was one drug different from the other?).

One critical step is checking for carryover. If the first drug still lingers in the system during the second period, it could inflate or deflate the results. The model tests for a sequence-by-treatment interaction. If it’s significant, the study is invalid. Many submissions get rejected because this test wasn’t done properly-or worse, ignored.

Also, missing data is a killer. If someone drops out after the first period, you lose their entire control. You can’t just average the rest. That’s why dropout rates above 10-15% often trigger regulatory concern. The whole advantage of crossover designs vanishes if you can’t compare each person to themselves.

Real-World Impact and Trends

Over 89% of the 2,400 generic drug approvals by the FDA each year use crossover designs. Companies like PAREXEL and Charles River run 75-80% of their bioequivalence studies this way. The savings are massive. One clinical trial manager reported saving $287,000 and eight weeks by switching from a parallel to a crossover design for a generic warfarin study.

But the field is evolving. The FDA’s 2023 draft guidance now allows 3-period designs for narrow therapeutic index drugs like digoxin and phenytoin, where small differences can be dangerous. The EMA is expected to formally recommend full replicate designs for all HVDs by late 2024. Adaptive designs-where sample size is adjusted mid-study based on early results-are also rising. In 2018, only 8% of FDA submissions used them. By 2022, that number was 23%.

Software tools like Phoenix WinNonlin make analysis easier, but open-source R packages like ‘bear’ offer more control-for those who know how to use them. The learning curve is steep. Biostatisticians need 6-8 weeks of specialized training to handle these designs correctly. That’s why so many failures happen: not because the method is flawed, but because it’s poorly executed.

When Crossover Designs Don’t Work

There are limits. If a drug has a half-life longer than two weeks, the washout period becomes impractical. You can’t ask volunteers to wait six months between doses. For these, parallel designs are the only option. Crossover also doesn’t work for drugs that cause permanent changes-like vaccines or chemotherapy agents. And if a drug causes side effects that linger (like severe nausea or dizziness), volunteers might not want to take it twice.

Still, for most oral solid dosage forms-tablets, capsules, suspensions-crossover is the gold standard. It’s proven, efficient, and accepted globally. It’s why you can buy a $5 generic instead of a $50 brand-name pill and know it’s just as safe and effective.

What’s Next?

The future of bioequivalence isn’t about abandoning crossover designs-it’s about refining them. With wearable sensors and continuous glucose monitors becoming more common, researchers are exploring whether real-time, non-invasive data can replace some blood draws. Imagine tracking drug absorption through skin patches or breath analysis. If that works, it could shorten washout periods or even eliminate them for some drugs.

But for now, the 2×2 and replicate crossover designs remain the foundation. They’re not perfect. They require precision, patience, and rigor. But they work. And that’s why, despite decades of innovation in drug delivery and analytics, this method still dominates the field.

What is the standard crossover design for bioequivalence studies?

The most common design is the two-period, two-sequence (2×2) crossover, where participants receive either the test drug then the reference (AB), or the reference then the test (BA), with a washout period between. This design minimizes variability by using each person as their own control.

Why are washout periods so important in crossover trials?

Washout periods ensure the first drug is completely cleared from the body before the second is given. If traces remain, they can interfere with the second period’s results, causing carryover effects. Regulators require at least five elimination half-lives between treatments to avoid this.

When is a replicate crossover design used?

Replicate designs (like TRR/RTR or TRTR/RTRT) are used for highly variable drugs (intra-subject CV >30%). These designs allow regulators to calculate within-subject variability for both test and reference products, enabling reference-scaled bioequivalence (RSABE) with wider acceptance limits.

What are the regulatory acceptance criteria for bioequivalence?

For most drugs, bioequivalence is proven if the 90% confidence interval for the ratio of geometric means (test/reference) for AUC and Cmax falls between 80.00% and 125.00%. For highly variable drugs, widened limits (e.g., 75.00%-133.33%) may be allowed under reference-scaled approaches.

Can crossover designs be used for all types of drugs?

No. Crossover designs are unsuitable for drugs with very long half-lives (e.g., >2 weeks), drugs that cause permanent effects, or those with lingering side effects. In these cases, parallel designs are required because the washout period would be too long or unsafe.

What are the main statistical pitfalls in crossover trials?

Common errors include inadequate washout periods, improper handling of missing data, failing to test for carryover effects (sequence-by-treatment interaction), and using the wrong statistical model. These flaws lead to study rejections and are among the top reasons regulators deny generic drug applications.

For anyone working in generic drug development, understanding crossover design isn’t optional-it’s essential. It’s the quiet engine behind the billions in savings from generic medications worldwide. Get it right, and you bring affordable medicine to market. Get it wrong, and you waste years and millions.

Priscilla Kraft

Love how this breaks down the math without drowning you in jargon 🙌 I used to think generics were just cheap knockoffs-turns out they’re basically bioengineering wizardry. Also, the 80-125% range? Mind blown. Who knew my body was doing all the heavy lifting as its own control? 😍

Sam Davies

Oh wow, another ‘crossover trial’ post? How original. I’m sure the FDA didn’t just copy-paste this from a 1992 textbook. Truly groundbreaking stuff. Next up: ‘Why water is wet and why we don’t just drink it in the shower.’

Christian Basel

FWIW, the intra-subject CV threshold for HVDs is 30% per EMA Guideline 2010, and RSABE is the only acceptable approach when s²wR > 0.294. Anything else is just statistical theater. And don’t get me started on the carryover tests-most submissions botch the sequence-by-treatment interaction. Half the time they don’t even report the p-value. Pathetic.

Jennifer Littler

Actually, the 2×2 design isn’t always ideal-even if it’s the default. I’ve seen studies where the washout wasn’t properly validated with PK modeling, and the regulators flagged it. You need to simulate the residual concentration profile, not just assume five half-lives is enough. Also, for drugs with enterohepatic recirculation, even a 14-day washout isn’t safe. We had to switch to a partial replicate for a generic bupropion last year because of this. It’s not just about time-it’s about pharmacokinetic behavior.

Jason Shriner

So… we’re paying $5 for a pill that’s ‘just as good’… but only if your body doesn’t hate it? And if you’re one of the 1 in 5 who metabolizes weirdly? Too bad. You’re just a statistical outlier now. The system doesn’t care. It just wants the 80-125% box checked. I’m not mad… I’m just disappointed. 😔

Alfred Schmidt

THIS IS WHY GENERIC DRUGS AREN’T SAFE!! THEY’RE TESTING ON 24 PEOPLE?!?!?!?!? WHAT IF ONE OF THEM HAS A RARE GENE VARIANT?!?!?!?!!?!? YOU’RE LETTING PEOPLE DIE BECAUSE OF STATISTICS!! I’M NOT JUST A COMMENTER-I’M A PHARMACIST WHO’S SEEN THE AFTERMATH!!

Sean Feng

The washout period thing is legit. I read about a guy who took his blood pressure med and then the generic a week later and his BP crashed. Turns out the first one was still in his system. Don’t be that guy.

Vincent Clarizio

Let’s be real-this entire system is a beautifully engineered illusion. We pretend that bioequivalence means therapeutic equivalence. But the body isn’t a test tube. It’s a symphony of gut flora, liver enzymes, circadian rhythms, stress hormones, and emotional states. Two people with identical AUC and Cmax can have wildly different clinical outcomes. The regulators don’t care because they’re not treating patients-they’re approving paperwork. And the companies? They’re not trying to cure disease. They’re trying to pass a statistical test. So yes, the pill works. But does it heal? Or just pretend to? The real question isn’t about sample size or washout periods-it’s about whether we’ve confused compliance with care.

Alex Smith

For anyone reading this and thinking ‘I’m not a scientist,’ you’re still part of this. Every time you choose a generic, you’re voting for a system that saves billions. But also-know the basics. Washout matters. Carryover kills. RSABE isn’t a loophole-it’s a lifeline for HVDs. And if your pharmacist says ‘it’s the same,’ ask them: ‘Which study design was used?’ That’s how you become an informed patient. Not a cynic. An advocate.

Adewumi Gbotemi

This is good. Simple words. I understand now why my medicine cost less but still work. Thank you.