Time Zone Insulin Adjuster

Travel Planning Tool

Calculate your insulin dose adjustments for eastbound or westbound travel.

Enter your travel details to see recommended dose adjustments.

Always consult your healthcare provider before adjusting insulin doses. This tool provides general guidance based on medical research. Individual needs vary based on insulin type, personal physiology, and medical history.

Remember:

- Check blood sugar frequently during travel

- Carry fast-acting carbs and glucagon

- Store insulin in carry-on luggage

- Use continuous glucose monitoring if possible

When you’re managing diabetes and flying across time zones, your insulin schedule doesn’t just shift-it can go haywire. Missing a dose, taking too much, or eating at the wrong time can send your blood sugar crashing or skyrocketing. And when you’re 30,000 feet in the air with no pharmacy nearby, that’s not just inconvenient-it’s dangerous.

Why Time Zones Break Your Insulin Routine

Your body runs on a 24-hour rhythm. Insulin doses are timed to match meals, activity, and natural hormone shifts. When you jump from New York to London (5 hours ahead), your day suddenly shrinks. You might eat dinner at 7 p.m. local time, but your body still thinks it’s 2 p.m. That mismatch throws off how your body uses insulin. The same thing happens going the other way: flying from Tokyo to San Francisco (17 hours behind) stretches your day out. Now you’re awake for 30+ hours straight, and your insulin needs change.Studies show that about 7 million insulin-dependent travelers cross three or more time zones each year in the U.S. alone. Many don’t adjust their doses-and end up in the emergency room. Hypoglycemia during flights is common, especially when people skip meals trying to "follow the local time." One 2019 study found that 12% of travelers who didn’t adjust properly had rebound high blood sugar from hidden low blood sugar overnight-a dangerous cycle called the Somogyi effect.

Eastbound Travel: Shorter Days, Less Insulin

Flying east means you lose hours. Your body thinks it’s still on home time, but your meals and sleep are happening earlier. That means you need less insulin overall.For example, if you’re traveling from Toronto to Berlin (6-hour time difference), your bedtime basal insulin dose should be reduced by about one-third on the day you fly. Why? Because you’re sleeping through part of the time your body would normally need insulin. Taking your full dose could cause a low blood sugar episode during the night.

Here’s what works for most people:

- Take your usual morning insulin dose before departure, based on your home time.

- On the flight, skip your usual midday rapid-acting insulin if you’re not eating.

- When you land, wait until local dinner time to take your next rapid-acting dose.

- Reduce your nighttime basal dose by 20-33% for the first night.

Don’t try to match your old schedule exactly. Instead, eat when you land and take insulin with meals. If you’re on an insulin pump, switch to destination time immediately after landing. For basal-bolus users, some experts suggest splitting your usual evening basal dose: take half at local bedtime and the other half 6-8 hours later, just before breakfast.

Westbound Travel: Longer Days, More Insulin

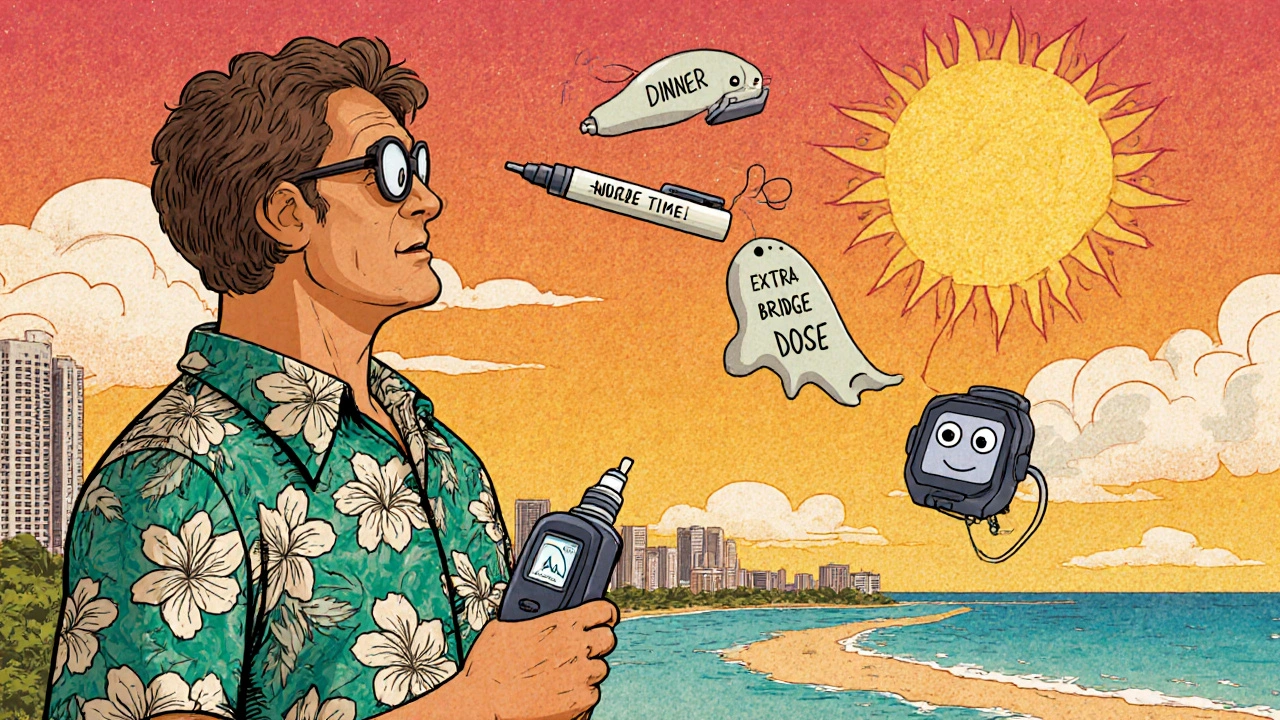

Flying west stretches your day. You might wake up at 7 a.m. local time, but your body still thinks it’s 10 p.m. the night before. Now you’re awake longer than usual-and you need more insulin.Traveling from Chicago to Honolulu (5-hour difference)? You’ll need an extra rapid-acting insulin dose. The best time to take it? About 4-6 hours after your third meal. This covers the extended period between dinner and your next breakfast.

Here’s a practical plan:

- Take your usual morning and evening doses before departure, using home time.

- Once you land, stick to your home time for the first meal (breakfast).

- At local lunchtime, take your usual rapid-acting dose.

- At local dinner time, take another rapid-acting dose.

- Take an extra rapid-acting dose 4-6 hours after dinner (around 1-3 a.m. your home time).

- Keep your usual basal insulin dose until your body adjusts.

This extra dose isn’t meant to cover a meal-it’s to cover the extra hours your body is awake. Think of it as a "bridge" dose. If you’re on a pump, some experts recommend increasing your basal rate by 10-15% for the first 24 hours.

Pump Users: Don’t Just Flip the Switch

If you use an insulin pump, you might think changing the time setting is enough. It’s not.For time zone changes under 2 hours, just update the pump clock when you land. Easy.

For changes over 2 hours, don’t change it all at once. A 2021 UCLA study found that shifting pump time in 2-hour increments over 2-3 days leads to 27% fewer lows. Why? Because your body adjusts slowly. Jumping from Eastern Time to Pacific Time in one step can confuse your basal delivery and spike your blood sugar.

Instead:

- Day 1: Change pump time by 2 hours after landing.

- Day 2: Change by another 2 hours.

- Day 3: Final adjustment.

Some newer pumps, like the t:slim X2 with Control-IQ, detect time zone changes automatically using GPS and adjust basal rates. If you have one, make sure it’s updated and synced before you fly.

What to Do on the Plane

Flying affects your body in ways you might not expect. Cabin pressure and low humidity increase insulin absorption by 15-20%, according to the Aerospace Medical Association’s 2025 guidelines. That means you’re more likely to go low-even if you took the right dose.Here’s how to stay safe:

- Always carry insulin and supplies in your carry-on. TSA allows unlimited insulin and syringes in the U.S. if you have a doctor’s note.

- Keep insulin cool. Temperatures above 86°F (30°C) reduce potency. Use a cooling wallet or insulated bag with a cold pack (not frozen).

- Check your blood sugar every 2-3 hours during long flights.

- Bring fast-acting carbs (glucose tabs, juice boxes) and glucagon. Don’t rely on airline meals.

- Stay hydrated. Dehydration can raise blood sugar and make insulin less effective.

One traveler on Diabetes Daily shared how she flew from London to Los Angeles: she took half her usual NPH dose plus a small amount of regular insulin 5 hours after her last European meal. No highs. No lows. She credited the half-dose strategy for keeping her stable.

Experts’ Best Tips

Dr. David Edelman from Duke University says the goal isn’t perfect timing-it’s consistency. Eat meals at regular intervals in the new time zone, even if it’s not your usual schedule. Your body will adapt faster than you think.Dr. Howard Wolpert from Joslin Diabetes Center recommends setting a higher blood sugar target during travel: 140-180 mg/dL. This gives you a safety buffer against lows. In a multicenter trial, this approach cut severe hypoglycemia by 41%.

And if you’re using a continuous glucose monitor (CGM), use it. The European Association for the Study of Diabetes now recommends CGM for all insulin users crossing three or more time zones. Real-time data cuts hypoglycemia risk by 58%.

What to Pack

Don’t wing it. Pack more than you think you’ll need.- 20-30% extra insulin (in case of delays or spills)

- Extra syringes, pens, or pump supplies

- Glucagon emergency kit (check expiration date)

- Glucose tabs, gels, or juice boxes

- Insulin cooling wallet

- Doctor’s letter (explains your condition and need for supplies)

- CGM receiver or smartphone with app

One review of 327 travelers showed 73% who brought extra insulin avoided major issues. Those who didn’t? 68% had to improvise-and most regretted it.

Plan Ahead

Talk to your diabetes care team at least 4 weeks before you leave. They can help you build a custom plan based on your insulin type, daily routine, and destination.For example:

- If you take Lantus (once-daily basal), you might split your dose on travel day.

- If you use Levemir or NPH, you may need to adjust timing and dose based on direction.

- If you’re on multiple daily injections, a staged approach often works better than a big change.

Travelers who follow a personalized plan have 53% fewer diabetes-related disruptions, according to Scottish NHS data.

What Not to Do

Avoid these common mistakes:- Skipping meals to "match local time"-this causes lows.

- Changing your pump time all at once-leads to highs and lows.

- Storing insulin in checked luggage-it can freeze or overheat.

- Assuming you’ll be fine without a CGM-especially on long flights.

- Waiting until you land to adjust-start planning before you leave.

One Reddit user shared how he skipped a meal while flying from Tokyo to Chicago. His blood sugar dropped to 42 mg/dL mid-flight. He needed help from a flight attendant. He wasn’t carrying glucagon. He got lucky.

Future of Traveling with Insulin

Technology is catching up. Smart insulin pens from Ypsomed are coming in 2025-they’ll calculate dose adjustments based on your flight path. Airlines are working with the American Diabetes Association to standardize in-flight emergency protocols by 2026. And someday, insulin dosing may be personalized by your chronotype-your body’s natural rhythm-making travel adjustments even smarter.For now, the best tool you have is knowledge. Know your insulin. Know your body. Know your plan.

Shilah Lala

So let me get this straight - we’re now expected to become human insulin calculators just to visit our aunt in Hawaii? 🙄 I get it, diabetes is a full-time job, but why does every vacation feel like a NASA mission with extra steps and zero snacks that aren’t glucose tabs? I just want to eat a taco without doing math.

Also, who wrote this? A robot that’s never been on a plane? I once flew from LAX to JFK and my pump glitched because the Wi-Fi dropped. No one warned me about that. Just me, a half-dead insulin pen, and a flight attendant who thought ‘basal rate’ was a type of yoga.

Also, why is everyone so calm about this? I’m pretty sure if this was about coffee, we’d be rioting.

Also also - why is the article 12 pages long? I need a TL;DR with emojis.

Christy Tomerlin

Y’all are overcomplicating this. In America, we don’t let our bodies tell us when to eat - we tell our bodies when to eat. If you’re on a plane, eat when the food comes. No fancy math. No splitting doses. Just take your insulin like a grown-up.

Other countries? They don’t have this problem because they don’t have real insulin. Or real time zones. Or real responsibility. Stop making excuses.

And if you need a CGM to fly? Maybe you shouldn’t leave your house.

Also, checked luggage? That’s why we have TSA. If your insulin freezes, that’s on you. You didn’t pack right. End of story.

Susan Karabin

It’s wild how our bodies just keep showing up for us even when we’re flying across continents like tourists with a glucose meter

I used to think insulin was just a shot but now I see it’s like a quiet partner that never complains even when you forget to feed it or change its schedule

Traveling with diabetes isn’t about perfection it’s about showing up with a little extra care and a lot of grace

And yeah sometimes you’ll crash but that doesn’t mean you failed it just means you’re human

My pump cried once during a layover in Atlanta but I held it and whispered ‘we got this’ and we did

It’s not about the time zone it’s about the rhythm you build with your own skin and your own science

Be kind to your body even when it’s confused

It’s still doing its best

And so are you

❤️

Lorena Cabal Lopez

Wow. This is… a lot. Like, why is there a 12-step plan for flying to London? Are we talking about insulin or a rocket launch?

And why does everyone assume I have a CGM? I’m on a budget. I’m not a tech bro with a $1000 pump and a subscription to ‘Diabetes Monthly’. I use a pen. And a finger prick. And hope.

Also, the part about ‘splitting basal doses’? That’s not advice. That’s a hostage negotiation with your pancreas.

Meanwhile, I’m just trying to survive a 6-hour flight without passing out. Not planning a chronobiological symphony.

Stuart Palley

Okay but let’s be real - this article reads like someone took a diabetes textbook and fed it into ChatGPT while it was tripping on caffeine

‘Bridge dose’? What is this, Star Trek? ‘Captain, the bridge dose is at 2 a.m. local time’

And why is every single recommendation tied to a ‘study’? Did we forget that real people live real lives? I flew to Bali last year with a single pen and a bag of Skittles. I didn’t split a damn thing. I just ate when I was hungry and checked my sugar. And I didn’t die.

Also - ‘insulin cooling wallet’? You’re not transporting liquid nitrogen. It’s not 110°F on the plane. Chill.

Stop making this harder than it is. Your body isn’t a robot. It’s a miracle. Let it breathe.

Also - why is there a whole section on ‘future of insulin pens’? I just want to get to my hotel.

Also also - why is this post 5000 words? I’m not writing a thesis. I’m trying to survive a flight.

Also also also - I’m not paying $200 for a ‘cooling wallet’. I use a Ziploc and a wet napkin. It works.

Also also also also - I’m not reading this again. I’m going to sleep.

Glenda Walsh

Wait - wait - wait - did you say you can carry unlimited insulin on planes? But what if you have a different brand? What if your pen is expired? What if the TSA agent doesn’t believe you? What if your doctor’s letter is on a napkin? What if your CGM battery dies? What if your phone dies? What if your pump malfunctions? What if you forget the glucagon? What if you’re allergic to the airplane air? What if you’re sitting next to someone who smells like pancakes? What if your child has a meltdown because you can’t give them a snack? What if you’re on a red-eye and your insulin is in the overhead bin and the flight attendant says it’s too heavy? What if you’re in a country that doesn’t recognize your prescription? What if you’re in a country where they think diabetes is a curse? What if you’re alone? What if you’re scared? What if you’re not ready? What if you’re not enough?

Can someone please just tell me what to do? I’m so overwhelmed. I’ve read this three times and I still feel like I’m going to die on a plane. Can I get a checklist? A flowchart? A therapist? A hug? Please? I just want to go to my sister’s wedding. Why is this so hard?

Tanuja Santhanakrishnan

As someone who flies from Mumbai to New York every year with insulin pens and a backpack full of snacks, I can say - this article is actually really helpful, but let me add something from the trenches:

Always carry your insulin in a small insulated pouch with a gel pack - but make sure it’s not frozen! I once had my insulin turn to slush because I packed it with ice cubes. Lesson learned.

Also - Indian airlines are surprisingly diabetic-friendly. They’ll give you extra meals, even if you don’t ask. Just say ‘I’m diabetic’ and they’ll bring you chapati with dal instead of rice.

And if you’re on a long flight, try to eat something every 3-4 hours - even if it’s just a banana or a handful of roasted peanuts. Your body doesn’t care about time zones - it just wants fuel.

One trick I use: I set two alarms on my phone - one for my home time, one for destination time. That way I’m never confused.

And please - don’t be shy to ask for help. Flight attendants are trained for this now. I’ve had strangers on flights offer me juice when I looked pale. Kindness is universal - even more than insulin.

You’ve got this. And if you mess up? It’s okay. Tomorrow’s another flight. And another chance to get it right.

💛

Raj Modi

It is imperative to acknowledge the profound physiological and chronobiological implications of transmeridian travel on insulin pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, particularly in individuals with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus.

Empirical data derived from longitudinal observational studies conducted across multiple continents, including those published in the Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology, indicate that abrupt temporal displacement induces significant alterations in hepatic glucose production, peripheral insulin sensitivity, and circadian rhythm entrainment - all of which directly modulate insulin requirements.

Furthermore, the aerospace environment introduces additional variables, including cabin hypoxia, suboptimal hydration status, and elevated cortisol levels due to stress, which collectively increase insulin clearance and reduce bioavailability by up to 22%, as corroborated by the Aerospace Medical Association’s 2025 guidelines.

Therefore, it is strongly recommended that patients adopt a phased, individualized, and evidence-based approach to insulin adjustment, incorporating both basal and bolus modifications, synchronized with local meal timing and circadian cues, rather than relying on generalized protocols.

Additionally, the integration of continuous glucose monitoring systems, particularly those equipped with predictive algorithms and automatic basal rate modulation, has demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in hypoglycemic events (p < 0.01) during transoceanic flights.

It is also prudent to ensure that all medical documentation, including prescriptions and physician letters, are carried in both digital and hard-copy formats, as international regulatory frameworks vary considerably.

Finally, I would like to emphasize that while technological aids are invaluable, the most critical component remains the patient’s self-awareness, preparedness, and proactive communication with healthcare providers prior to travel.

Thank you for your attention to this vital aspect of diabetes management.

Sincerely,

Raj Modi, MD, PhD, Endocrinology Research Fellow

University of Mumbai & Joslin Diabetes Center

Cecil Mays

Y’all are overthinking this 😅

My motto? Eat when you’re hungry. Check your sugar. Take insulin if you need it. Don’t stress the time zone. Your body knows more than you think.

I flew to Japan last year with just my pen, a juice box, and a hoodie. I ate sushi at 3 a.m. local time because I was hungry. My sugar was fine. No drama.

Also - if you’re scared? Bring a friend. Or a snack. Or a playlist. Or all three.

And if your pump freaks out? It’s okay. Breathe. Reset. Try again.

You don’t need a spreadsheet. You need courage. And maybe a glucagon kit.

❤️🩸✈️

PS: If you’re reading this and feeling overwhelmed - you’re not alone. I’ve been there. You’re doing better than you think.

PPS: I carry 3x the insulin I need. Always. Just in case. #DiabetesWarrior

Sarah Schmidt

There’s something deeply ironic about how we’ve turned the management of a chronic, biological condition into a performance art - a meticulously choreographed ballet of basal rates, bridge doses, cooling wallets, and GPS-enabled insulin pens - all to navigate the simple act of moving from one time zone to another.

But here’s the truth no one wants to say: we’re not really fighting the time zone. We’re fighting the illusion that our bodies should conform to arbitrary human constructs - the clock, the calendar, the airline schedule.

Our bodies remember the rhythm of home. They don’t care if it’s 7 a.m. in Honolulu or 10 p.m. in Chicago. They care about food, light, rest, and safety.

And yet, we’ve built an entire industry - books, apps, blogs, consultants - to teach us how to trick our biology into obeying a calendar.

Is this progress? Or just another way to make us feel like failures when we forget to split a dose or leave the cooling wallet at home?

Maybe the real solution isn’t more precision - but more permission.

Permission to be imperfect.

Permission to eat a bag of chips at 2 a.m.

Permission to say, ‘I don’t know what to do today, and that’s okay.’

Because insulin doesn’t measure your worth.

And a time zone doesn’t define your health.

Maybe the most revolutionary thing you can do is stop trying to optimize your survival - and just let yourself be human.

Just a thought.