Medication Interaction Checker for Acid-Reducing Drugs

When you take a proton pump inhibitor like omeprazole or an H2 blocker like famotidine for heartburn, you might think you’re only helping your stomach. But what you’re really doing is changing the chemistry inside your digestive tract - and that can mess with how other medicines work. This isn’t a rare edge case. It’s happening right now to millions of people who are taking common drugs for high blood pressure, HIV, cancer, or fungal infections - often without knowing it.

How Acid-Reducing Medications Change Your Stomach

Acid-reducing medications (ARAs) include proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) like omeprazole, esomeprazole, and lansoprazole, and H2-receptor antagonists (H2RAs) like ranitidine and famotidine. These drugs don’t just reduce acid - they raise the pH in your stomach from its normal range of 1.0-3.5 to 4.0-6.0. That might sound harmless, even helpful. But for many drugs, that small change makes all the difference.

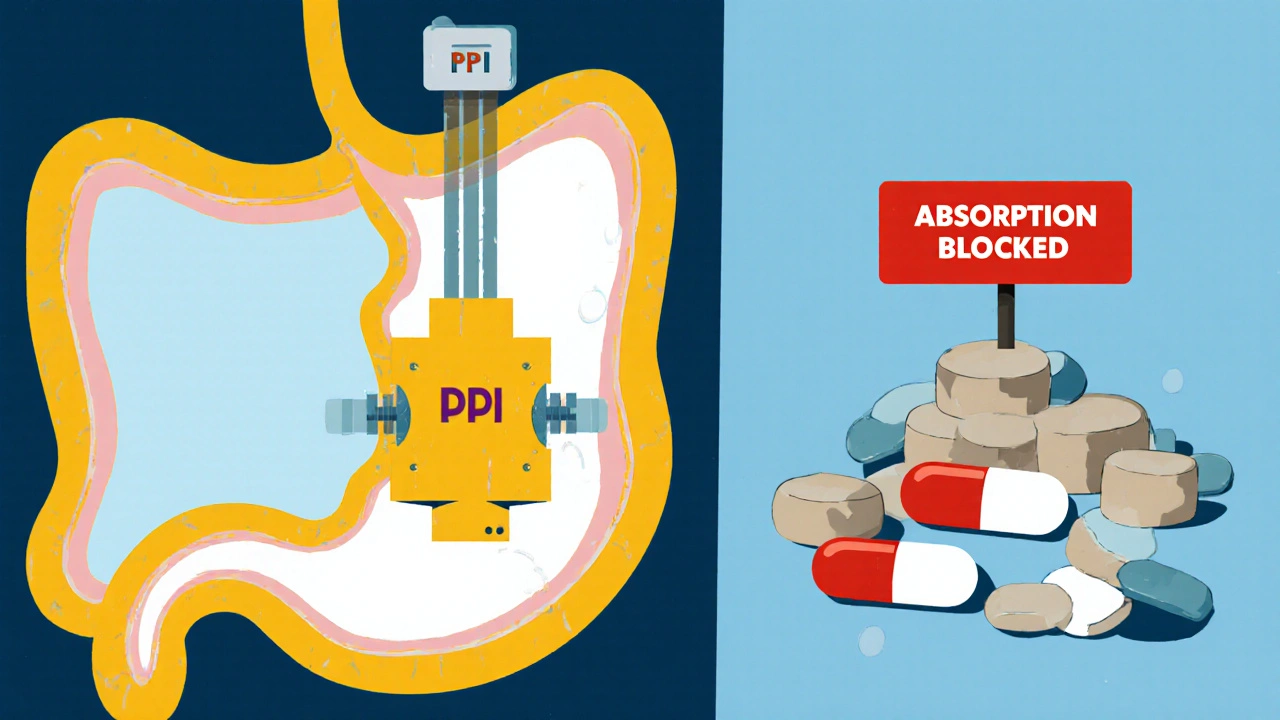

PPIs are especially powerful. Once taken, they shut down the acid pumps in your stomach lining for up to 24 hours. H2 blockers work faster but last only 8-12 hours. That means if you’re on a daily PPI, your stomach is essentially neutral for most of the day. And that’s the problem.

Why pH Matters for Drug Absorption

Most oral drugs are either weak acids or weak bases. Their ability to dissolve and get absorbed depends heavily on the pH around them. Think of it like salt in water - some things dissolve better in acid, others in water that’s closer to neutral.

Weakly basic drugs - like atazanavir (for HIV), dasatinib (for leukemia), and ketoconazole (for fungal infections) - need an acidic environment to dissolve properly. In a normal stomach, they break down easily and get absorbed. But when acid is suppressed, these drugs stay clumped together, like sugar crystals that won’t melt. They don’t dissolve, so they don’t get absorbed. Studies show atazanavir’s absorption drops by up to 95% when taken with a PPI. That’s not a small drop - it’s enough to let HIV replicate again.

On the flip side, weakly acidic drugs like aspirin or ibuprofen dissolve better in higher pH. But their absorption usually increases by only 15-25%, which rarely causes problems. The real danger lies with drugs that have a narrow therapeutic window - where even a small change in blood levels can mean the difference between treatment and failure.

Drugs That Are Most at Risk

There are about 15 commonly prescribed drugs that are known to be severely affected by acid-reducing medications. The most critical ones include:

- Atazanavir - An HIV drug. Taking it with a PPI can make it useless. Viral load can spike from undetectable to over 10,000 copies/mL.

- Dasatinib - Used for chronic myeloid leukemia. Absorption drops by 60%. Treatment failure rates rise by 37% in patients on PPIs.

- Ketoconazole - An antifungal. It becomes nearly ineffective with PPIs. Many doctors now avoid it entirely because of this.

- Mycophenolate mofetil - An immunosuppressant. Reduced absorption can lead to organ rejection in transplant patients.

- Iron supplements - Especially ferrous sulfate. Acid helps convert iron into a form your body can use. Less acid = less iron absorbed.

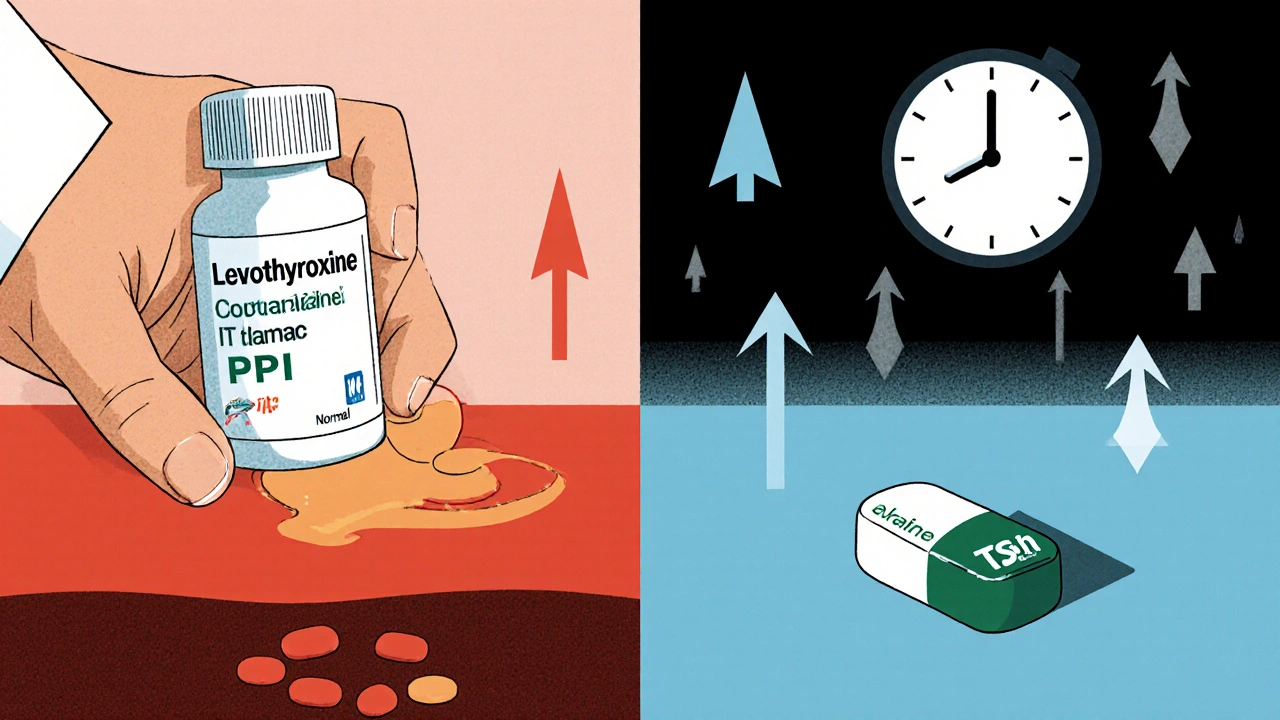

- Levothyroxine - Thyroid hormone. Some patients report needing higher doses when on PPIs, even though their thyroid levels don’t improve.

The FDA has flagged these interactions and requires warning labels on the packaging. But many patients never see those labels. Doctors don’t always ask about heartburn meds. And pharmacists don’t always catch it unless they’re actively looking.

PPIs vs. H2 Blockers: Which Is Worse?

Not all acid reducers are created equal. PPIs are far more disruptive than H2 blockers. Why? Because they last longer and lower acid more completely.

A 2024 study in JAMA Network Open found that PPIs reduce absorption of pH-dependent drugs by 40-80%. H2 blockers? Only 20-40%. That’s a big gap. If you have to take an acid reducer long-term, an H2 blocker like famotidine is usually a safer choice - if it still controls your symptoms.

Also, immediate-release pills are more vulnerable than extended-release versions. And enteric-coated tablets - designed to dissolve in the intestine - can actually break down too early if stomach pH rises. That means the drug gets exposed to acid in the wrong place and can get destroyed before it’s absorbed.

Real-Life Consequences

This isn’t theoretical. People are getting sick because of this.

On Reddit, a user wrote: “My viral load went from undetectable to 12,000 after I started Prilosec for heartburn.” Another said: “My doctor didn’t tell me Nexium would interfere with my blood pressure meds - my readings were consistently 20 points higher.”

In a 2023 study of over 12,000 patients, those taking dasatinib with a PPI had a 37% higher chance of treatment failure. The FDA’s adverse event database logged over 1,200 reports of therapeutic failure linked to acid reducers between 2020 and 2023. Atazanavir, dasatinib, and ketoconazole made up the top three.

And it’s not just about effectiveness. Some drugs become toxic if absorption drops too low. The body tries to compensate by metabolizing them differently - leading to unpredictable side effects.

What You Can Do

If you’re on a medication that could be affected, here’s what actually works:

- Ask your doctor if you really need the acid reducer. Up to half of long-term PPI users don’t have a clear medical reason to be on them. Stopping might solve both problems.

- Check your meds. Look up your prescription on Drugs.com or Medscape. Search for “acid reducer interaction.” If it’s flagged, talk to your pharmacist.

- Time your doses. If you must take both, take the affected drug at least 2 hours before the acid reducer. This helps - but doesn’t eliminate the risk.

- Use antacids instead. Tums or Maalox can be used occasionally with a 2-4 hour gap. But they don’t last long, so they’re not good for daily use.

- Get a pharmacist review. A 2023 study showed pharmacist-led checks reduced inappropriate ARA use by 62% in older adults.

Some clinics now use electronic alerts in their systems. If you’re on atazanavir and your doctor tries to prescribe omeprazole, the computer will pop up a warning. But not all systems are set up that way - and not all doctors pay attention.

The Bigger Picture

Over 15 million Americans take PPIs long-term. Many do it without ever being properly evaluated. The American College of Gastroenterology says 30-50% of those users don’t need them. And every time someone takes one unnecessarily, they’re putting other medications at risk.

The cost? Around $1.2 billion a year in the U.S. alone - from failed treatments, repeat hospital visits, and extra tests. That’s not just money. It’s avoidable suffering.

Drug makers are starting to respond. New medications in development are being designed to work regardless of stomach pH. Some use special coatings, others use entirely different delivery systems. But for now, the burden is on you and your care team to spot the problem.

What’s Next

Future tools will help. AI models are being trained to predict these interactions with over 89% accuracy. Gastric pH monitors - small, wearable devices - are being tested to see how your stomach actually responds to meds. And guidelines are getting stricter.

The FDA now requires new drug studies to test solubility across pH levels 1.0 to 7.5. If a drug is poorly soluble above pH 5 and is a weak base, it must carry a warning. That’s progress.

But until then, the safest thing you can do is question every acid reducer you’re prescribed. Ask: Do I really need this? What else could it affect? You’re not just treating heartburn. You’re managing your entire medication regimen.

Can I take antacids instead of PPIs to avoid drug interactions?

Yes - but only for occasional use. Antacids like Tums or Rolaids work quickly and can be taken 2-4 hours before or after other medications. They don’t raise stomach pH for long, so they’re less likely to interfere with drug absorption. But they’re not good for daily heartburn control. If you need something every day, talk to your doctor about switching to an H2 blocker like famotidine, which has a lower interaction risk than PPIs.

Does timing help reduce the interaction?

It helps a little, but not enough to rely on. Taking a weak base drug like dasatinib 2 hours before a PPI can reduce absorption loss by 30-40%. But since PPIs suppress acid for up to 24 hours, the stomach remains too alkaline for proper dissolution. For high-risk drugs like atazanavir, timing isn’t safe - you need to avoid PPIs entirely.

Why do some people say their thyroid meds don’t work when they’re on PPIs?

Levothyroxine needs an acidic environment to be absorbed properly. PPIs reduce stomach acid, which can lower its absorption by 10-25%. This often shows up as rising TSH levels even when the dose hasn’t changed. The fix? Take levothyroxine on an empty stomach, at least 4 hours before any acid reducer. If symptoms persist, your doctor may need to increase the dose.

Are there any acid reducers that don’t interfere with other drugs?

No acid reducer is completely safe if you’re taking a pH-sensitive drug. But H2 blockers like famotidine have a much lower risk than PPIs. Antacids are safest for short-term use. Newer drugs like vonoprazan (a potassium-competitive acid blocker) are being studied - early data suggests they may have fewer interactions, but they’re not yet widely available.

How do I know if my medication is affected?

Check the drug’s prescribing information or use a reliable tool like Drugs.com or Medscape. Search for “drug interaction” with your acid reducer. If it says “contraindicated,” “avoid,” or “significant interaction,” don’t combine them. Ask your pharmacist to run a full interaction check - they have access to tools doctors don’t always use.

Can I stop my PPI cold turkey?

Don’t stop suddenly if you’ve been on it for months. Your stomach can rebound with even more acid, causing worse heartburn. Work with your doctor to taper slowly - often over 2-4 weeks. If you’re on it for no clear reason, stopping is the best move. Studies show most people feel better without it after a short adjustment period.

If you’re on a chronic medication for HIV, cancer, or a serious condition, don’t assume your doctor knows about this interaction. Bring up acid reducers by name - whether it’s omeprazole, pantoprazole, or even over-the-counter Tums. Your life could depend on it.

Gabriella Jayne Bosticco

Wow, I had no idea my Tums could be messing with my blood pressure med. I’ve been popping them like candy since my last gastric flare-up. Guess I’m switching to ginger tea and praying.

Thanks for the wake-up call.

Iska Ede

Ohhh so THAT’S why my fungal infection came back with a vengeance after I started taking omeprazole…

Classic. We get told to ‘just take a pill’ and nobody tells us the pill is sabotaging five other pills. 😤

Someone needs to make a TikTok about this. #PPIsAreEnemies

Bailey Sheppard

This is one of those posts that makes you pause and re-read every prescription you’ve ever taken.

I’ve been on famotidine for years thinking it was ‘the safe one.’ Now I’m wondering if I should’ve been asking more questions. Thanks for laying this out so clearly - no jargon, just facts. Needed this.

Christine Eslinger

It’s not just about drug absorption - it’s about systemic ignorance. We treat stomach acid like a villain to be eradicated, not a vital enzyme activator that’s been working for 2.5 billion years.

Pharma profits from chronic use. Doctors are overworked. Patients are told ‘it’s fine’ without context.

This is a failure of medical education, not personal negligence. The real tragedy? Most people who take PPIs long-term don’t even have GERD - they have stress, poor diet, or lazy lifestyle choices.

We’ve outsourced our biology to a pill. And now we’re paying the price with failed cancer treatments, uncontrolled HIV, and confused endocrinologists.

Let’s stop calling it ‘heartburn.’ Call it ‘the silent war inside your gut.’

And yes - if you’re on levothyroxine, take it 4 hours before your acid reducer. And no coffee for 30 minutes after. It’s not magic. It’s chemistry.

Denny Sucipto

My grandma took omeprazole for 8 years. Last year she got diagnosed with stage 3 kidney disease. No one ever connected the dots.

I showed her this post. She cried. Said she thought the pill was just ‘for the burn.’

We’re all just trying to feel better. But sometimes the fix makes the whole house burn down.

Thanks for writing this. I’m printing it out for my mom’s next appointment.

Emanuel Jalba

OMG I KNEW IT!! I told my doctor for months that my HIV meds weren’t working but he kept saying ‘your adherence is fine!’

Turns out I was on Prilosec for ‘indigestion’ - which I didn’t even have! 😭

Now my viral load’s back to zero. But what if I’d waited another 6 months? I could’ve been dead. Or contagious. Or both.

Y’all need to STOP trusting your doctor blindly. Ask. Ask. ASK. 🙏

Also - PPIs cause dementia. I read it on a blog. So… yeah. 😈

Heidi R

So you’re telling me the entire gastroenterology industry is built on a lie?

Let me guess - the same people who sell you PPIs also sell you ‘gut health’ supplements that do nothing.

And you wonder why Americans are the sickest people on earth.

Pathetic.

Girish Pai

As a pharmacologist from Mumbai, let me tell you - this is textbook pharmacokinetics. The stomach pH shift alters ionization state, which directly impacts passive diffusion across enterocytes.

Atazanavir’s logP drops from 3.8 to 1.2 above pH 5.0. That’s not a ‘drop’ - that’s a cliff.

And yes, famotidine is marginally better - CYP3A4 inhibition is minimal compared to PPIs’ irreversible binding.

But why are you still using oral ketoconazole? It’s obsolete. Use itraconazole or posaconazole. No pH dependency. Done.

Stop using 2000s protocols. The world moved on.

Shilpi Tiwari

Wait - so if I take my levothyroxine at 5 AM and my famotidine at 10 AM, is that safe?

I’ve been doing this for 2 years and my TSH is still 6.2. My endo says ‘it’s fine.’

Is this why my fatigue never goes away?

Also - is there a list of all 15 high-risk drugs? Can someone share a link? I’m compiling a spreadsheet for my book club. We’re all on something.

Kristi Joy

I’m a nurse and I see this every day. Someone comes in with a new prescription for omeprazole - and they’re on 7 other meds. No one connects the dots.

But here’s the thing - you don’t have to be perfect. You just have to be aware.

If you’re on any of these drugs, ask your pharmacist: ‘Is this going to mess with my heartburn pill?’

They’ll know. And they’ll care.

You’re not being annoying. You’re saving your life.

Holly Powell

Let’s be real - this post is 87% fearmongering wrapped in a PubMed citation.

Yes, PPIs interact. But the absolute risk of treatment failure is <0.5% in the general population.

Meanwhile, PPIs reduce upper GI bleeding by 70% in high-risk patients. The benefit-risk calculus is not binary.

Also - ‘15 million Americans take PPIs’? So? 30% of them are on them for a legitimate reason. The rest? Maybe they have functional dyspepsia. Or anxiety. Or a bad diet.

Stop treating every common medication like a poison. You’re not a patient. You’re a pharmacovigilance bot.

Christine Eslinger

Actually, Holly - you’re right about one thing: the risk is low for most people.

But here’s the thing - when you’re one of the 0.5%, you don’t care about statistics.

You care that your HIV viral load spiked. You care that your transplant got rejected. You care that your thyroid meds stopped working after 10 years of stability.

That’s not fearmongering. That’s lived reality.

And if you’re a nurse, a pharmacist, or a doctor - you owe it to your patients to ask the question.

Not because it’s scary.

Because it’s simple.

‘Are you taking anything for heartburn?’

That’s it.

That’s all it takes.